On Modality Commoditization

And what might come next

Welcome to The Century of Biology! This newsletter explores data, companies, and ideas from the frontier of biology. You can subscribe for free to have the next post delivered to your inbox:

Today, we’re going to briefly pause the hub-and-spoke series (first articles here and here) to consider the broader evolution of drug discovery technologies over time—and the impact this may have on biotech strategy.

Enjoy! 🧬

Ten years ago, the scientologist (no, not scientist) Bob Duggan sold his American biotech startup to AbbVie for $21 billion (no, not million). His company, Pharmacyclics, had developed a highly promising cancer drug and was handsomely rewarded for it. In fact, Duggan’s payout of over $3.5 billion was reported to be one of the largest returns from a public buyout in history.

Aside from the eccentricities of Duggan as a founder—and the other large characters involved that made all of this book worthy—this was a relatively normal deal. A Big Pharma company was under serious pressure to find a new source of revenue as one of its blockbuster products reached the end of its patent exclusivity. An American startup’s breakthrough drug became that new source.

Much of the biotech industry is predicated on this dynamic. Small startups have become the primary source of innovation, running the majority of early-stage clinical trials each year. Big Pharma companies buy these startups at a rich premium to continually replenish their pipelines.

But things are changing. A decade later, Duggan is back. This time, he’s got a new drug that beat Keytruda—Merck’s cancer immunotherapy drug that grosses $30 billion a year—in a clinical trial. Crucially, Duggan didn’t find this drug in an American lab. He licensed it from a Chinese company.

Unlike Pharmacyclics, this story didn’t end with a massive multi-billion dollar acquisition. Instead, Merck went to the same source, buying their own version of the same drug type for $500M from another Chinese company.

This is a really big deal. Much like we recently saw in AI, China has become a serious competitive threat in biotech, demonstrating the capacity to rapidly develop new drugs that can rival—or surpass—those being produced in American labs. In other words, “the drug industry is having its own DeepSeek Moment.”

Consider another example. As GLP-1 drugs became an explosive success, pharma companies raced to get their hands on their own next-generation versions of this product class to compete with Novo Nordisk and Eli Lilly for market share. Again, Merck looked to China, acquiring an oral GLP-1 drug for $112M upfront. The deal was backloaded with milestones up to $1.9B based on commercial success.

For context, Viking Therapeutics, an American biopharma company with an oral GLP-1/GIP agonist in its pipeline, currently has a $3.8B market cap. Rather than pursuing a wholesale buyout of Viking, why not just grab a molecule from China for a bargain and see if it works?

In a moment where the biotech market is depressed, the heightened external competition makes things even harder. While the M&A market has already been slow, now founders and investors alike are losing sleep over deals falling apart at the last minute because of stealthy Chinese competitors they had never even heard about.

This whole situation has spurred a lot of analysis. Some of my favorites so far are David Li’s reflection as a Chinese American biotech startup founder, his subsequent analysis in the Timmerman Report, Bloomberg’s coverage, and Alex Telford’s characteristically thoughtful take on the question: Will all our drugs come from China?

Here, I want to zoom out and consider how we got here.

In 1987, Merck was featured on the cover of Fortune Magazine as “America’s Most Admired Corporation” for “betting on magic molecules.”

In the decades prior, Merck scientists were responsible for producing breakthrough molecules for hypertension, some of the most successful vaccines in history (Maurice Hilleman, one of the most prolific vaccinologists of all time, was a scientist at Merck), the first statins, and entire new classes of antibiotics.

Now, for two of the hottest products in the market, Merck has looked outside of the American biotech startup ecosystem—which was still struggling to come into existence in 1987—and acquired molecules from the Chinese ecosystem—which wasn’t a major source of innovation until very recently.

Clearly, the global drug discovery industry has undergone considerable evolution. At this juncture, I think it’s worth considering the long arc of commoditization for drug discovery technologies, as well the implications of this historical pattern for the future of the industry.

The Long Arc of Modality Commoditization

Let’s think about biologics.

For most of history, nearly all drugs were plant-based chemicals with a useful impact on human physiology that humans had serendipitously discovered. Over time, tools were developed to more systematically search through chemical space for useful small molecules. Another small category was the set of proteins, such as insulin, that could be isolated from animals and used to treat disease.1

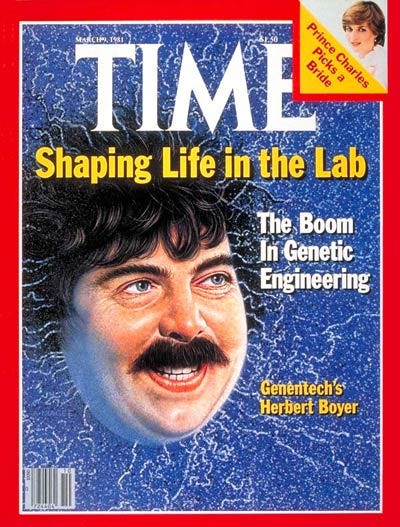

The recombinant DNA revolution that gave rise to Genentech’s founding in 1976 planted a seed of radical change. Using the tools of genetic engineering, it became possible to produce biologically derived molecules to mitigate disease in entirely new ways. Fifty years later, there are nearly as many biologics approved each year as there are small molecules.

But at first, few people believed this new type of drug would be possible. And a similarly small cohort of people in the entire world had any of the requisite skills necessary to even try. It’s easy to lose track of the fact that Genentech started out as a fringe operation full of scientists working day and night in a uniform of tee shirts, jeans, and running shoes.

As Peter Thiel would frame it, the company had an important shared secret that the rest of the world didn’t understand yet.

Success changed this. When Genentech achieved their first product breakthroughs, the market responded with fanatical optimism. Nothing—not even Princess Diana—seemed more exciting than engineering life.

When Genentech went public in 1980, the initial share price was $35. Within one hour of trading, the price nearly tripled, jumping to $88. It was an absolute frenzy of excitement.

By 1983, American firms had invested half a billion dollars into new biotech firms. Two years later, the U.S. Department of Commerce estimated that there were roughly two hundred biotech firms that had raked in nearly $2B in investment in total.

In retrospect, this was clearly a hype bubble. Recombinant DNA technology was still nascent. More big wins like recombinant insulin didn’t quickly follow. There were still looming regulatory questions. Manufacturing biologics at scale was a challenge.

The initial boom was followed by a period of disillusionment and contraction. In 1985, a reporter in Massachusetts wrote,

If all this seems far too much for scientists with little or no business track record, you're right. For that reason alone, two trends have become dominant in the post-boom biotech industry.

First, at the few firms which are better capitalized, the scientists/founders/chief executives are hiring, or being forced to hire a traditional “numbers cruncher” as company president or chief operating officer. These are seasoned business executives from major companies, not the groves of academe. At BioTechnica International in Cambridge, they just hired a 20 year Dupont man. At Collaborative Research, in nearby Lexington, the new president formerly headed a Johnson and Johnson subsidiary. So did the new president of Damon Biotech in Needham Heights.

Second, momentum in the industry appears to have shifted in favor of large corporations. Especially those which supplied a big share of biotech's original funding through equity purchases and research and development contracts. In a sense, the good response to the first public stock sales by the new biotech firms only postponed the bad news for many of them. Now, when the young companies badly need another infusion of capital, corporations like Dupont, W.R. Grace and Co., Monsanto, and Eli Lilly & Co. are instead directing their investments toward inhouse biotech capabilities. As a result, industry experts are predicting a spate of mergers. Nelson Schneider, an E.F. Hutton analyst, believes that as many as two thirds of the biotech companies will either merge together or be acquired by major drug or chemical manufacturers.

In other words, the industry was forced to mature and actually realize revenues, and incumbent organizations wised up and started to build out their own biotech capabilities internally. By the end of the 1980s, most biotech stocks had lost three quarters of their value.

But there was an important kernel of truth at the center of this bubble: recombinant DNA really was a transformative tool for making new medicines. Even in a more sober environment, the companies with the resources, technology, talent, and grit to survive kept churning out products.

After synthetic insulin, Genentech produced seven more biologics throughout the 80s and 90s. Amgen, another early biologics pioneer founded in 1980, had their own string of breakthrough medicines that set them apart from the rest of the struggling competition. Regeneron, which was founded in 1988 after the initial boom, differentiated themselves over time with a keen focus on human genetics and a powerful technology platform for producing monoclonal antibodies—which proved to be one of the most important types of biologic.

While there were still many skeptics, the scope of biologics continued to expand across medicine, reaching the point in 2022 where their volume of approvals was first on par with small molecules. (The graph we looked at earlier.)

The commercial success for these first movers is also undeniable. Genentech was acquired by Roche in 2009 for $46.8B, where it still operates as a highly impactful independent subsidiary. Amgen currently has a market cap of $168B. Regeneron is now worth $78B, with a share price nearly 4000% higher than at their IPO.2

This evolution is almost a textbook example of the phenomenon known as the Gartner hype cycle. An initial “innovation trigger” causes a big spike in hype and excitement. When the hype isn’t immediately justified, the market cools. If the initial trigger has substance, there is a more gradual rebound over time.

And we do seem to have entered a “plateau of productivity.” The ability to produce biologics is no longer a secret guarded by a small set of companies. Scientists around the world have now spent decades refining the tools for developing these drugs. An entire wave of companies has cropped up to offer antibody development as a service.

Consider Adimab. Founded in 2007, the company used the next generation of antibody engineering tools—namely yeast surface display—to rapidly produce new molecules for a large number of partners. They’ve now worked with over a hundred different partners, with “more than 75 clinical programs originating from our platform.”

Given that Adimab is a private company, it’s hard to do an apples-to-apples comparison of their commercial success relative to first movers like Amgen or Regeneron. But extrapolating from their $1.1B valuation during a secondary transaction ten years ago, the rough ballpark is that they’ve grown into a ~$5-10B business.

Now, if companies want access to a different technology, or have distinct preferences for cost, speed, geography, or a multitude of other factors, they can choose to go with FairJourney Biologics (valued at ~$900M in 2024), OmniAb (~$400M market cap), Ablexis, Specifica, Creative Biolabs, Twist Biosciences, Alloy Therapeutics, or somebody else. This list is illustrative and far from exhaustive.

What’s interesting to note is that across each generation, the magnitude of the businesses decreases by roughly one order of magnitude. The first movers grew into ~$100B+ companies. The leading service providers that followed became ~$10B+ companies. Now, the new entrants in the discovery market are ~$1B+ companies.

To me, this looks like the textbook definition of commoditization, which is the gradual process of making a good or service into a commodity and competing on price. A commodity is a good or service that is interchangeable with other commodities of the same type.

Think about electronics. At the start, very few companies could produce the best TVs. These companies charged a large premium. Over time, this premium was competed away. Now, a large number of companies sell massive flat screens packed with smart features for hundreds of dollars at Costco. This is commoditization.

Similarly, it’s getting increasingly hard to distinguish between antibody discovery providers, with many companies using similar technologies to produce antibodies against the same drug targets.

So far, we’ve exclusively focused on the history of antibodies. But I want you take a leap with me that will potentially annoy some drug developers: no discovery technology is immune from the inescapable pull towards commoditization—like virtually every other technology.

For big and small molecules alike, once discovery technologies—whether it’s high-throughput screening, in silico screening, in vitro or in vivo models, or an analytical assay—become standardized, companies around the world will compete to offer them as a service.

This is The Long Arc of Modality Commoditization.

Over time, revolutionary ideas become universal building blocks for the next wave of innovation.

Biotech’s Strategic Evolution

In parallel to the standardization and commoditization of discovery technologies, biotech investing became professionalized. With many decades of refinement, the industry moved towards standardized models for valuing companies. New strategies emerged.

One strategy that has gained considerable popularity is the “fast follower” approach where a new drug is developed to be “best-in-class” for a target with other drugs on the market, rather than to be “first-in-class” for a wholly new drug target.

An analysis published in 2003 pointed out two key benefits to the “quest for the best.” First, these drugs clearly have a lower risk profile because the target has already been validated by a drug approval based on human evidence. Investors typically talk about the amount of “biology risk” they are underwriting for a new target hypothesis. Second, the difference in risk didn’t seem to be commensurately rewarded. In fact, looking at drug launches between 1991 and 2000, the majority of blockbusters were developed against known targets, and the fast-followers created more value than the riskier novel drugs.

A clear example of this strategy is Merck’s acquisition of the oral GLP-1 agonist we looked at earlier. Novo Nordisk and Eli Lilly took on a lot of risk proving out the efficacy of the first GLP-1 drugs. Now, other companies are competing for fast-followers with improved properties, like formulation in a pill rather than dosing via injection.

Many biotech investors have taken this type of analysis to its logical extreme. As the size of early-stage rounds—and the funds financing them—have swelled, it’s gotten harder to justify risking big pools of capital on totally unproven target hypotheses. In practice, this has led to substantial crowding around validated targets.

To make things even more efficient, “virtual biotechs” became prominent around the 2010s, where all research and development was outsourced to discovery partners like Adimab. The goal was often to rapidly produce a best-in-class molecule against a known target that could be sold to a Big Pharma for late-stage development and commercialization.

This industry history is essential for understanding the recent explosion of Chinese licensing deals, because many of the top outsourcing partners were Chinese Contract Research Organizations (CROs).

WuXi Biologics, a sprawling Chinese company offering a large suite of biologics discovery and manufacturing services, has become the second largest outsourcing partner in the world, capturing over 10% of the global market.

Now, the extremely logical strategic evolution from China, encoded in a new set of policies in 2015, is to develop their own drugs rather than just remaining a service provider. In a world where most people are using commoditized discovery technologies against the same drug targets, China has two key advantages:

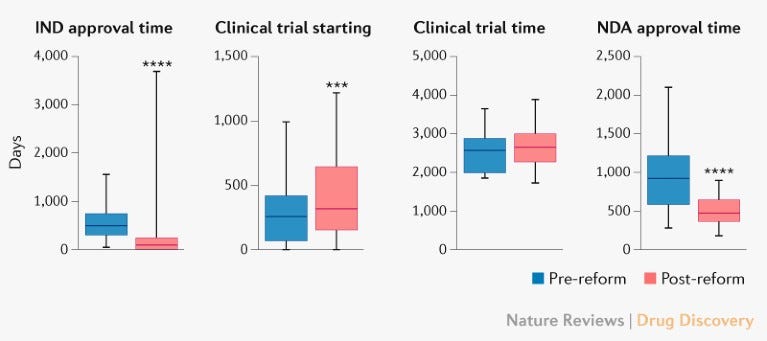

Speed. The new set of reforms made it possible to launch clinical trials much more quickly.

Cost. Salaries for Chinese scientists are a fraction of those for American scientists. An army of highly-skilled—often American-trained—researchers can be thrown at far more problems.

With these advantages, Chinese startups and biopharma companies have seemingly saturated the space of known drug targets. Companies place cheap “call options” on a wide range of targets in the form of pre-clinical or early-stage assets. When a specific target or product idea gains traction with Big Pharma, these “options” can be exercised by pouring gas on the existing program to race it forward.

This puts intense pressure on the fast-follower strategy. When American scientists go to bed at night, the machines in the labs of their competitors on the other side of the world keep humming.

So far, we’ve traced the history of commoditization for drug discovery technologies and the subsequent professionalization of biotech investing. These changes help to contextualize the “DeepSeek moment” for the industry.

Now, let’s consider where value might accrue in the future.

AI Could Be The Last Wave of Commoditization

Over the last few years, a lot of money has been poured into companies with moonshot visions to transform drug discovery with AI. Some companies, like Xaira Therapeutics, which started with $1B in “Seed” funding, aim to develop their own medicines. But many others, such as EvolutionaryScale, Profluent, Chai Discovery, and Latent Labs, are considering strategies more akin to Adimab, where this new technology is offered as a broadly enabling piece of infrastructure.

When Latent Labs was launched, Tony Kulesa at Pillar wrote:

What emerged was a clear vision for democratizing access to advanced AI tools in drug discovery. While every biotech and pharma company searching for therapeutic molecules understands the role AI can play, most aren’t in a position to develop their own models and tooling at the cutting edge. Simon’s insight was that by giving partners instant access to the best tools, Latent Labs could accelerate drug design across the entire industry.

The combination of large funding rounds and new business models has drawn a mix of intrigue and skepticism. Andy Dunn at Endpoints wrote, “Latent’s launch shows how AI-focused startups can buck tradition in biotech. Most biotechs are formed around a molecule, research paper or key intellectual property. Instead, Latent’s investors are betting on AI talent in Kohl and Alex Bridgland, another ex-DeepMind developer of AlphaFold, to figure it out.”

Let’s consider the bear case and the bull case for this investment thesis.

In the bear case, none of these technical directions—whether the focus is on novel data generation, scaling models, architecture improvements, or some combination of all three—meaningfully move the needle when compared to commoditized technologies.

In his field notes from the Molecular Machine Learning conference at MIT, Simon Barnett from Dimension wrote, “my interpretation of [the co-founder of Adimab] Dr. Wittrup’s talk was that he views monoclonal antibody (mAb) discovery as a mostly solved problem and that the impact of machine learning (ML) to this domain is exaggerated.”

If AI techniques prove to only make a small quantitative difference on problems like antibody discovery, the companies offering these solutions could join the long line of companies competing to offer these services. We could expect to see <$1B companies rather than ~$50-100B+ generational behemoths.

What about the bull case? Squint with me for a second, and imagine a trajectory of AI progress that leads to a qualitative difference, genuinely moving us into a world of design rather than discovery. Imagine a model that spits out zero-shot predictions of the platonic antibody—perfect affinity and specificity, exquisitely optimized along every dimension—for any target. Put in a target product profile (TPP), get out a drug.

That would probably be a pretty big deal.

One commonly invoked comparison is Cadence Design Systems, which is a $66B company that generates most of their revenue from licensing their software and IP for electronic design automation (EDA) for the semiconductor industry. For high-value domains, the best design tools can be extremely valuable. Could the “Cadence for Pharma” be even bigger?3

Is there any evidence for this technological trajectory?

Last year in March, the Baker Lab at the University of Washington published a preprint entitled Atomically accurate de novo design of single-domain antibodies. Building on decades of leading work on computational protein design, they introduced an AI model that could effectively generate miniature antibodies (called VHHs or nanobodies) for a given target.

These results stirred up an enormous amount of excitement and interest—including the $1B bet to launch Xaira. But the work was a proof of concept, not a magical black box capable of spitting out perfect antibodies. Scientists pointed out that the affinity of the generated nanobodies for their targets were still too weak to become drugs. And nanobodies are strange proteins that don’t fully resemble human antibodies—again limiting their clinical utility in many applications.

Slightly less than a year later, the Baker Lab “significantly updated” their original preprint, renaming it to Atomically accurate de novo design of antibodies with RFdiffusion.4 As you might guess, the title was changed because the work was extended beyond just VHH design. The updated preprint also demonstrated the design of single-chain variable fragments (scFvs) which are another antibody format that have two variable domains rather than the single variable domain of a VHH.

Another important update was a response to the concerns about affinity. The authors wrote, “While initial computational designs exhibit modest affinity, affinity maturation using OrthoRep enables production of single-digit nanomolar binders that maintain the intended epitope selectivity.” In other words, AI doesn’t produce perfect binders yet, but they can be quickly tuned with existing experimental techniques.

So that’s about a year. At the risk of drawing a line between two data points, progress seems pretty rapid. Moving forward, what if somebody creates a giant set of training data for affinity using OrthoRep and that step moves out of the realm of atoms and becomes encoded in the world of bits in the form of improved model weights?

In the next five years, what will prevent the continued march from VHHs to scFvs to full-fledged monoclonal antibodies?

Again, just squinting, it appears that we could be on the cusp of digitizing the development of biologics. If the advantages in speed and cost—and potentially quality—are substantial, this could lead to consolidation in the discovery market, where new entrants quickly attract a sizable portion of outsourced work, displacing incumbents.

Now let’s consider what the world looks like if we take the concept of “foundation model” seriously. What if important underlying patterns of biological structure and function are learned across many tasks? As Simon Kohl from Latent Labs told Endpoints, “The vision is grander. I think we can expand from there, and we will find over time many other areas beyond the molecular interactions level will be steerable with generative models.”

So if this—or any part of what I just outlined—is true, some of these companies could become really big.

But one of the biggest threats is likely to be… commoditization! After all, the entire “DeepSeek Moment” framing comes from the abrupt leap in AI capabilities from Chinese research groups with less resources than their American counterparts.

And there are already signs of this.

So far, Demis Hassabis, the co-recipient of the Nobel Prize for protein structure prediction and CEO of both DeepMind and Isomorphic Labs, has been betting on algorithm innovation rather than the development of a proprietary data moat for model defensibility. In a recent interview, he said, “make your algorithms better, your models better. You do have enough data — if you were innovative enough on your algorithm side.”

It’s been amazing how quickly serious algorithmic competitors have emerged.

In May of 2024, Isomorphic and DeepMind published a paper describing AlphaFold3, their latest and greatest structure prediction model. In September of 2024, Chai Discovery published and open-sourced a state-of-the-art model. Roughly two months later, a research group at MIT produced another open-source version with comparable performance.

It will be interesting to see where value accrues in this new AI race.

No matter what, all of these advances will open up new opportunities for innovation in other parts of the drug discovery stack.

Biological Insights Could Become More Valuable

Not all biotech platforms focus on therapeutic modalities. Some companies focus on the other side of the coin: the identification of new biological targets to drug. In Steve Holtzman’s “typology of platform companies” these are “insight platforms.”

Focusing on disease insights comes with its own basket of strategic challenges. In his original post, Holtzman wrote,

HOWEVER, Genus 2, Species A Platform Companies face a set of challenges not faced by Genus 1 Platform Companies. These arise intrinsically from the fact that the output of the Genus 2, Species A Platform Companies is data/information/insights, NOT, as with the Genus 1 Platform Companies, New Chemical Entities (NCEs) and biologic therapeutics.

The history of data in the biopharmaceutical industry is the history of its commoditization.

Companies whose “life’s blood” is drugs/products have a vested interest in rendering data “pre-competitive” (or, at least doing so after they have had proprietary access for a time). They win based on their products; they don’t want to be held captive by the owner of the information.

A more restrictive intellectual property (IP) environment: gone are the days when a transcriptional profile showing over-expression of a gene in a diseased tissue (or a genetic mutation in the diseased state) could get you an issued patent of the logical form, “a method of treating disease X comprising modulating target A by any means” (with dependent claims stating that the “means” could be an antibody, an antisense, an RNAi, a gene therapy, a small molecule, etc.).

Moreover, the demands of the customer base became more expansive over time. Whereas, in the 1990s, most big pharma customers were willing to agree to terms that restricted their use of the data to the discovery and development of small molecule drugs (because that is all they did), in the present all pharmas/big biotechs would demand the right to exploit the data for all therapeutic modalities.

Finally, the Genus 2, Species A Platform Company has and builds its expertise in the generation, curation, and interrogation of the data. It does not come into existence or can afford to cultivate/invest in significant capabilities in drug discovery/development in one or more therapeutic modalities, or in-depth biology/translational capabilities, in one or more diseases.

The Net Result: the Genus 2, Species A Platform Company ends up abandoning its data/information business to build and become a drug discovery and development business.

Let’s break this down.

First, it’s important to understand that data generation technologies have their own long arc of commoditization. (That’s technology, folks!) Next, the main issue in the past has been the asymmetric negotiation with larger partners—who used to have proprietary access to discovery technologies that gave them an unfair advantage in actually creating chemical matter against new targets.

This dynamic has already started to shift. The growth and maturation of the CRO industry has already made it possible for insight companies to show up to partner discussions with their own NCEs rather than just patents around target insights.

What if AI accelerates this dynamic? Over time, as modalities become increasingly commoditized, the time and cost from target insight to developable chemical matter could be compressed even further.

In this world order, the pendulum could swing. New disease insights could become more valuable than any incremental starting point in chemical space against a known target.

The $100B+ GLP-1 success story, after all, was built on a biological insight, not a modality advance.

There are a few economic and technical realities that could slow down progress on this front.

In terms of economics, as David Yang nicely laid out, part of the reason GLP-1 was a pharma success rather than a biotech success is because of the centrality of M&A in the industry. Most early-stage biotech investors are banking on large acquisitions for liquidity, which means they keep a very close eye on the shopping list of pharma buyers. And pharma buyers really don’t like spending billions of dollars to test new biological hypotheses—especially when the size of the market opportunity is uncertain.

How can we change this and unleash a new wave of more innovative medicines? We’ll need to continue to decrease the time and cost for every part of the stack—from discovery, to development, to commercialization.

Doing this would make early-stage drug discovery a lot more valuable.

Improving discovery and commercialization both seem like technology problems. Accelerating development may require new technology and regulatory reforms. Taking a page out of China’s book (for a change!) and studying their recent reforms could be a good starting point for the latter.

On a technical level, it’s important to recognize that modeling human biology is a much more difficult AI problem than modeling a specific modality. Consider two questions. Does my antibody bind this target with higher affinity? What impact will activating the GLP-1 receptor have on the totality of human physiology? The tools to definitively answer the first question in the lab are readily available. The answer to the second question can’t fully be known until first-in-human trials, because our pre-clinical models are only rough approximations of human biology.

More effectively simulating human biology will likely require substantial data generation and continued progress in new AI paradigms.

Over time, tackling these economic and technical challenges could dramatically reshape the biopharma landscape, leading to a new wave of commercial biotechs advancing bold new therapies.

But all of these rapidly compounding technologies could also lead to an even more radical departure from traditional biotech business models in the long run.

Moats Could Look Very Different

In most industries, there are multiple viable strategies to create enduring competitive advantages over competitors. The canonical 7 Powers framework developed by Hamilton Helmer is an attempt to enumerate the most prevalent approaches.

The 7 Powers are:

Scale Economies — A business where per unit costs decline as volume increases.

Network Economies — A business where the value realized by a customer increases as the userbase increases.

Counter Positioning — A business adopts a new, superior business model that incumbents cannot mimic due to the anticipated cannibalization of their existing business.

Switching Costs — A business where customers expect a greater loss than the value they gain from switching to an alternate.

Branding — A business that enjoys a higher perceived value to an objectively identical offering due to historical information about them.

Cornered Resource — A business that has preferential access to a coveted resource that independently enhances value.

Process Power — A business whose organization and activity set enables lower costs and/or superior products that can only be matched by an extended commitment.

(For a deeper understanding, check out Helmer’s 7 Powers book, or read Abi Tyas Tunggal’s great summary.)

At the risk of oversimplifying, only two of these Powers matter in biopharma. Big Pharma companies benefit from Scale Economies because they can amortize the costs of development and commercialization with revenue from their existing portfolio. For biotechs, basically the only real source of Power is control over a Cornered Resource in the form of new intellectual property (IP).

As Peter Drucker once wrote, “The pharmaceutical industry is an information industry.” The value of a small molecule drug has nothing to do with its physical instantiation, which is worth very little. The ability to charge the highest margins for any physical product in existence is purely a function of the IP. Once the IP expires, generic drug makers can swoop in and offer substantially lower prices.

This is “The Biotech Social Contract,” as Peter Kolchinsky at RA Capital would frame it. Scientists and entrepreneurs are rewarded patent exclusivity for innovation. But the exclusivity is finite. When it expires, the innovative drugs become cheap commodities for all future generations.

The looming concern with commoditization is that this could soon become China’s Social Contract with the biopharmaceutical industry—as long as they can produce equivalent IP cheaper and faster.

But what if there was a different way to build a defensive moat in biotech?

There are some early examples pointing to orthogonal forms of defensibility. It’s hard to know what genericization will look like for CAR-T therapies—a new form of medicine centered around a process for engineering a patient’s own cells to eliminate cancer. In Kolchinsky’s book on The Biotech Social Contract, he actually expressed concern about this. Companies marketing these drugs may derive moats from Process Power rather than from a Cornered Resource around IP.

Now let’s run this forward over time.

Personalized cancer vaccines are another form of therapy with this type of form factor. There is no single composition of chemical matter at the core of this type of medicine. Instead, each dose is produced by a complex combination of patient measurements, algorithms, and manufacturing steps.

This has really interesting consequences. For the first time, this could be a medicine with Network Economies. Because each dose is designed with an algorithm, the quality could be improved as more data is collected. Patients could benefit from taking the medicine produced by the company with the largest data moat. This approach also clearly benefits from Process Power. Over time, the winner for this new modality could even accrue a clear Branding advantage as the market leader.

If more forms of medicine start to look like this, we could see a wave of biotechs directly competing to establish themselves as an entirely new generation of pharmaceutical company.

In considering this, I can’t help but think of my good friend Packy McCormick’s writing around Vertical Integrators. In his words, there are several defining characteristics of these companies:

Vertical Integrators are companies that:

Integrate multiple cutting-edge-but-proven technologies.

Develop significant in-house capabilities across their stack.

Modularize commoditized components while controlling overall system integration.

Compete directly with incumbents.

Offer products that are better, faster, or cheaper (often all three).

For Vertical Integrators, the integration is the innovation.

Just as before, there are clear challenges with this strategy. There is no free lunch!

A massive hurdle will likely be financing and capital formation. This approach to company creation is totally distinct from how most biotech investors think about generating returns. It’s completely unclear if a Big Pharma company would be willing to buy a company with such a complex product without definitive proof of commercial viability.

Winners in this space may need to look elsewhere for capital. One possible option is to tap the growing pool of “Deep Tech” venture capital that is focused on underwriting breakthrough advances in hardware and innovation in the world of atoms. Later stage investment could come from generalist growth equity firms rather than traditional biotech crossover funds.5

Attempting to build a Vertical Integrator in biotech is not for the faint of heart.

Combining multiple technologies in new ways is hard. Financing will be hard. Scaling commercial efforts will be hard. It could take a lot longer to achieve success.

Because of all of these factors, biotech investing could start to mirror the rest of the private market’s evolution. Companies could stay private longer. Consider SpaceX, which has raised nearly $10B over its 23 years as a private company and is now valued at $350B. Liquidity for early investors and employees has come from secondary markets rather than M&A transactions or IPOs.6

Despite the hurdles, the prize is potentially massive.

Measurement tools that were once unimaginable are now commonplace in biology. The foundational insights that gave birth to the last wave of generational biotechs have been refined and commoditized. AI is accelerating biology’s transition into a predictive and quantitative discipline.

Tackling big problems that have evaded prior approaches—like cancer, infectious disease, and brain health—will likely require creative solutions that integrate multiple digital and physical building blocks.

If the companies solving these global problems establish moats in new ways, we could see the first $1T+ biotech firms come into existence.

The public biotech market is pretty gloomy right now. And for American biotechs, the steady uptick in Chinese acquisitions has further threatened their prospects of success. As Adam Feuerstein wrote, “Sentiment is lousy and the bad mood is relentless, to the point where people are seriously wondering if a sector turnaround is ever possible.”

At the same time, the early-stage market is brimming with potential. The pace of technological innovation is equivalently relentless. Entrepreneurs equipped with hard-earned lessons and powerful tools are pursuing wholly new ideas.

Perhaps the right question isn’t whether the market will rebound. Because it will. Markets are cyclical. Instead, the question is if biotech is on the cusp of a phase shift into something new altogether. If it is, it’s never been a better time to build.

In other words…

Biotech is Dead. Long Live Biotech!

Thanks for reading this essay on the commoditization of therapeutic modalities and its strategic implications.

If you don’t want to miss upcoming essays, you should consider subscribing for free to have them delivered to your inbox:

Until next time! 🧬

Early on, many of these rudimentary biological medicines consisted of extracted serums rather than purified proteins. For example, several “antitoxin” therapies were developed by immunizing animals, leading to the production of antibodies in the blood. The serum containing the antibodies would have a therapeutic effect. We were using antibodies as drugs before we knew what they were!

This is also noteworthy because Regeneron’s buzzy IPO in 1991 was considered to be a second bubble of biotech hype at the time as more products started to come to the market.

It’s worth noting that Cadence has already acquired a molecular docking company and has pharma customers.

Drop the “single-domain,” it’s cleaner.

One encouraging data point for this strategy is Enveda. They have managed to attract technology investors, deep tech investors, growth equity firms, and strategics. They are now approaching $400M of capital raised with a cap table that is totally dissimilar from most biotech companies.

From a venture perspective, SpaceX can sound like a tough investment. Sure, it’s huge, but it’s still private 23 years later, which is far outside of a ten year fund cycle! But in practice, Founders Fund, which has deployed massive amounts of capital into SpaceX across several funds, has been one of the top-performing firms in the market. Just like biopharma, private markets and venture capital have evolved considerably over time.

Packy. Thanks for linking to this.. WOW... so much to digest... this is a serious loaf of information and logic

Another highly impactful essay, which I will re-read in a few days time. One thought: for the sake of argument let’s assume the “bull” case regarding ML & antibody generation, enabling the industry to generate mabs of exquisite sensitivity and affinity. Now, of the >10000 diseases (majority of which are orphan), how many do you think are sufficiently well understood at the molecular level to enable them to be addressed using our new, improved methodology? I honestly don’t know the answer here but suspect that it’s a minority (and a small one at that). Thus, the rate-limiting step is likely to be fundamental disease understanding rather than the challenges inherent in drug discovery/development. (I think Robert Plenge at BMS has written about this extensively). Furthermore, consider two very high profile (and prevalent) diseases; Alzheimer’s & Parkinson’s. Here, we’ve experienced either clear cut failure or minor success despite (apparently) identifying the causal agent & pathway. I suspect “better” mabs will only shift the dial a little at most.