Hub-and-Spoke Biotechs: Nimbus Therapeutics

Building an "evergreen" drug discovery engine

Welcome to The Century of Biology! This newsletter explores data, companies, and ideas from the frontier of biology. You can subscribe for free to have the next post delivered to your inbox:

Enjoy! 🧬

Biopharma is a profoundly acquisitive industry. Pharmaceutical giants need to maintain their massive cash flows by developing or acquiring new products—and this balance has swung overwhelmingly towards acquisition over time. This type of “Big Brother” relationship has been around since the biotech industry’s inception, when Genentech first partnered with Eli Lilly in 1978 to manufacture and market recombinant insulin. Genentech was ultimately acquired by Roche in 2009.

This is a blessing and a curse. The massive incumbents provide critical near-term resources but impose a cap on long-term growth—you get snapped up as soon as you have a great product. As Roivant CEO Matt Gline put it, “I think it is interesting the extent to which we lionize [M&A] as sort of the end all, be all. That what success looks like for a biotech company is getting sold.”

So maybe “Big Brother” isn’t quite the right analogy. Attempting to build a generational biotech is a bit like the journey of a baby crab avoiding being devoured by its own mother.

As David Yang traced in a great thread, the critical ingredient for transitioning from a biotech startup to an enduring business is the independent development of a blockbuster drug that brings in over $1B in sales. But this is incredibly expensive to do, so as soon as companies get data hinting at a blockbuster product, there is intense pressure—especially from investors—to sell to pharma, or another biotech looking to make the phase transition to become a “next-gen” biopharma acquirer.1

This is especially tricky for platform companies, which can get bought wholesale for their lead programs before ever getting a chance to compound as a business. Recent examples are the Carmot, Prometheus, and Karuna acquisitions. In each case, the founders decided to launch brand new companies to keep pursuing the original vision of their previous companies.2

What if there was a way to benefit from large M&A transactions while keeping the core platform and team of a company intact over time?

This is exactly the problem that hub-and-spoke biotech companies aim to solve. The innovation is in corporate structure, where a central hub company containing key technology or personnel is fire-walled from spoke companies centered around specific products. With this structure, spoke companies with valuable assets can be sold off to pharma—much like picking a ripe apple off of a branch instead of chopping down an entire tree for one fruit.

To better understand this model—and some of its different permutations—we’re going to cover three important case studies in a new series. We’ll be covering Nimbus Therapeutics, BridgeBio, and Roivant Sciences. Each company has created billions of dollars of value by putting their own spin on the hub-and-spoke structure.

As we compare and contrast these different businesses, we’ll consider many strategic questions. What problem is each business trying to solve with this model? Is the added complexity worth it? Which ideas were viable? Which ideas failed?

For now, let’s get a better sense of how this works with our first case study.

Nimbus Therapeutics

In March of 2011, Bruce Booth, a partner at Boston-based Atlas Venture and industry blogger, published a post with a compelling hook:

Bill Gates has just backed one our new startups – Nimbus Discovery LLC – as part of an extension to the seed tranche. Here’s the press release.

It might come as a surprise to some, but Bill Gates has been a long-time biotech supporter: he was a founding investor in ICOS and was on that Board for 15 years, and importantly, he’s also one of the largest investors in Schrödinger, the world’s leading computation drug discovery company, and our founding partner with Nimbus.

So, with this financing, we’re launching Nimbus out of ‘stealth mode’. Here’s the story.

What? Bill Gates was investing in computational drug discovery back in 2011? It’s like reading a dispatch from the future—but it was written over a decade ago. This was one of the early waves of excitement centered around the idea that computers could revolutionize drug discovery.

This new company aimed to combine three central ideas into a unified whole.

The first big idea, as we can see above, was that advances in computational chemistry had made the technology ready for prime time. These new tools, like Schrödinger’s “WaterMap” software package for modeling the interaction of solvents (in the human body, this is water) with molecular structures, could provide a differentiated wedge for developing new drugs against “exciting but difficult-to-drug” targets.

Schrödinger, which is still a leading company in computational chemistry, was founded in 1990, nearly twenty years before striking this partnership to launch Nimbus. The early 90’s were a very exciting time for computer technology.

The same year Schrödinger was founded, Microsoft made over $1B in revenue—the first time a software company had ever achieved that feat. People were also really excited about the possibility that computers could make drug discovery much more efficient.

Vertex Pharmaceuticals, founded a year before Schrödinger, was based on Joshua Boger’s vision of “rational drug design” with a major focus on computer modeling. Here’s an interesting excerpt from The Billion Dollar Molecule by Barry Werth:

From a business standpoint, what differentiated Vertex’s story—and what Boger now intended to flog most assiduously—were three things: Vertex’s integrated approach, its first-among-equals attention to chemistry, and its lineage, which tracked impressively through the mainline of the pharmaceutical industry and Merck, then Wall Street’s favorite company. “Smart ex-Merck guys making drugs with computers,” Aldrich said, encapsulating.

Vertex wanted to become the next Merck. But Schrödinger wanted something different. Perhaps inspired by Microsoft’s success, the vision for the company was to sell their modeling software to drug discovery companies rather than making drugs themselves.

In 2010, just a year before the Nimbus deal, Bill Gates—one of the biggest believers, and beneficiaries, of the software revolution—invested $10M into Schrödinger. David Shaw, another billionaire very keen on the potential of scientific modeling, was also a key early backer.

I’m reading between the lines here, but the mentality at Schrödinger seemed to be, “We’ve got the resources to invest in hardcore R&D for this software. When it gets good enough, this is going to be an absolutely enormous software business.”

So the Nimbus deal probably seemed like a win-win. Schrödinger could keep focusing on what “made its beer taste better,” as Jeff Bezos would put it, by cranking on software R&D. Setting up a parallel entity that was run by drug discovery experts from Boston would get them closer to the downstream economics of pharma without too much distraction.

This new company would get access to Schrödinger’s scientists, compute, and unreleased algorithms. It would also get target exclusivity—meaning Schrödinger couldn’t turn around and work on the same targets with somebody else. In exchange for all of this, Schrödinger got somewhere around 10% ownership of the company as a founding partner.3

So that’s idea number one: build on top of Schrödinger’s cutting-edge computational chemistry platform.

The second central idea was about how to leverage the computational predictions that were produced. Nimbus was founded in 2009, a year after a global financial crisis. The company wanted to be as capital efficient as possible.4 To do this, their plan was to build a “virtually integrated, globally distributed” model.

First, get model predictions from Schrödinger without needing to build the computational platform. Next, send the first batch of predictions to offshore Contract Research Organizations (CROs) to make experimental progress as cheaply as possible.5 Then, feed the data into the models and make new predictions.

Wash, rinse, repeat.

As Booth put it, “We’re really pushing the envelope on virtual drug discovery.”

The third central idea was to use the hub-and-spoke model.

In theory, they had just established a repeatable process for rapidly producing new differentiated assets at a very low cost. Here, they thought about the problem we outlined earlier. Would they have to start and sell a brand new company for every asset? Yes, but they could do that from within a broader umbrella.

Here’s what they designed:

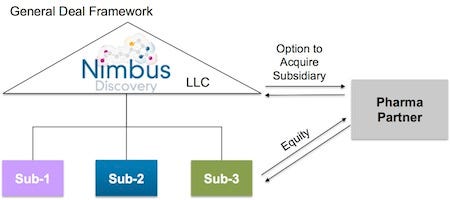

Let’s start at the center. The main hub of Nimbus is a passive limited liability corporation (LLC) holding company. Investors fund this entity. Shareholders like Schrödinger own part of this LLC in exchange for services. This LLC owns a series of distinct subsidiaries—one of which is the actual management company. The remaining subsidiaries house the actual IP related to any specific target.

Any target-specific subsidiary can be sold without impacting the others. These are the apples that can be plucked from the tree.

When apples are plucked (target-specific subsidiaries are sold) the money flows back through the LLC to shareholders and investors. Because the holding company is an LLC, it isn’t taxed like a C-corporation. So the sale is taxed once, not twice. In Booth’s words, this “solves the classic drug discovery illiquidity problem (where it takes 7-10 years to get liquid via M&A or IPO); this LLC structure enables us as shareholders to cycle capital back to our investors in a tax-efficient manner on a per project basis.”

Going a click deeper, here’s a look at the deal framework that this model makes possible:

Pharma partners (or investors) can make “equity or equity-like” investments in specific R&D programs. These deals provide capital from partners without diluting the parent company, and can even be structured around pre-negotiated terms based on milestones. Nimbus would know upfront how much they would make in a sale if R&D was a success.

It basically creates an “evergreen drug discovery stage biotech” that can continually recycle returns to investors—and to the hub company—and keep cranking on R&D for new projects.

This all sounds really cool in theory. But how does it actually work in practice? Studying this business in 2024, we have the benefit of historical evidence.

Historical Transactions

I won’t bury the lede: this model has worked really well. Nimbus has now sold multiple assets—including a sale worth $4B in cash and $2B in milestones—while keeping the team and platform intact. As the current CEO Jeb Keiper puts it, “The day after a transaction everybody at Nimbus walks back into work and keeps working on the rest of the pipeline.”

This is awesome!

But like any substantial journey, there have been real challenges along the way. The Nimbus team learned which of their initial ideas were viable—and which weren’t.

Early on, the idea was to use the Nimbus engine to crank out a large number of pre-clinical drug programs in parallel. “Invest $10 million to get 5 development candidates in 2 years.” Before even generating data for an Investigational New Drug (IND) application, they’d license these promising assets off to pharma. Simple as that!

But nobody bit. Just like today, the proof is in the clinic—not the computer or the lab. Ultimately, Nimbus needed to file an IND and generate Phase 1 data themselves. But with this data in hand, they were able to make their first major deal.

In 2016, Nimbus delivered it’s “Apollo mission” by selling their Acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC) subsidiary (literally named Nimbus Apollo) to Gilead for $400M in upfront cash and $800M more in potential milestone payments.6

This was a big inflection point. They’d now shown that they could rapidly move from one of Schrödinger’s virtual screening hits into the clinic. This sale also proved out the hub-and-spoke model. It truly “enables the sale of the eggs, not the goose.”

But could the goose lay another golden egg?

The Nimbus team got back to work to see. But as their CEO Jeb Keiper wrote, it wasn’t all smooth sailing:

The transition had its challenges though: we had begun working in clinical development, hired staff, and now were reset to an early-stage preclinical company. All our resources in chapter 1 had begun funneling to the lead program, and with only $67 million raised over 7 years, Nimbus was not exactly “robust” at an enterprise-level. We had just 22 people by the end of that year, 15% of the company having departed following the Gilead deal.

Despite the hub-and-spoke structure, the company still needed to concentrate on making sure their Apollo mission could actually reach escape velocity. Once it was gone, they needed to restructure and get back to R&D—which they used 5% of the Gilead proceeds to do.

What happened next highlights the amount of skill, perseverance, and ultimately, luck, that can be behind the big headline deals in the news.

In 2017, Nimbus arranged another spoke deal using the mechanics we discussed above. They gave Celgene options to buy two of their target franchises: TYK2 and STING. According to Keiper, “Nimbus retained full ownership and control of the programs in exchange for funding and pre-programmed exits of $400 million each for Phase 1b data in a few years.”

In theory, this was going to be a rerun of the Gilead deal. But that’s not how things went.

Instead, in 2019, Celgene was acquired by Bristol Myers Squibb (BMS) for $74B. Even in an extraordinarily acquisitive industry, this was big news: it was the largest pharmaceutical acquisition in history.

But for Nimbus, that wasn’t the fact they cared about. It was a much bigger deal that BMS already had a TYK2 program of their own.

This dynamic plunged the company into more troubled water. BMS would want to retain their option to buy Nimbus’s TYK2 program in the event that theirs failed. It was much less certain what would happen if BMS’s program succeeded.

Over the next few years—in the middle of a global pandemic—Nimbus and BMS entered into a legal battle over what would happen with these two programs. The major concern was that BMS would be incentivized to kill Nimbus’s TYK2 program to eliminate competition:

“There is a credible threat that, unless stopped, BMS will slow down or kill the development of Nimbus’s Tyk2 asset. First, BMS has the incentive to protect its leading Tyk2 inhibitor, deucravacitinib, from future competition. Second, BMS has an incentive to avoid additional payments to Nimbus,” the complaint says. “BMS does not have the same incentives to develop Nimbus’s Tyk2, as Celgene did before its acquisition by BMS, given that this would lead to the cannibalization of BMS’s own Tyk2 sales.”

Ultimately, the two companies settled out of court, leaving Nimbus with full ownership of its TYK2 program. At this point, the program had entered Phase 2b trials. With this major twist of fate, Nimbus prepared to finally scrap their hub-and-spoke LLC structure and go public as a clinical-stage biotech.

But that’s not how the story went either! Because of a massive black swan event—the largest pharma acquisition of all time—Nimbus had full ownership of this program. During COVID, Nimbus was also operating in the largest bull run for public biotech stocks of all time. But as their IPO plans crystallized, the market sharply reversed. The IPO window for biotechs swung firmly shut.

The Nimbus management decided to hang tight and continue privately financing this program. This proved to be a wise choice. That year, BMS gained full approval for their TYK2 drug for psoriasis. Most analysts expected that this drug (now marketed as Sotyktu) would come with a severe safety warning because of the risks associated with targeting this family of enzymes. But it didn’t. The allosteric inhibition of TYK2—which was the same mechanism of Nimbus’s drug—now had the potential to grow into a blockbuster autoimmune franchise.

Interest in Nimbus’s TYK2 franchise exploded. Ultimately, Takeda acquired the spoke for $4B in cash and $2B in milestones—ten times the return of the original pre-negotiated Phase 1 deal with BMS.

Today, Nimbus remains a private company. After two major sales, their hub-and-spoke LLC structure remains intact. The engine is still humming. Reflecting on the company’s North Star, Keiper says,

Our mission remains the same: We design breakthrough medicines. Our objective in dollars and cents terms is to again shoot for the moon, to become again a multi-billion-dollar biotech. But our ambition is far greater than that. Nimbus has an opportunity to build a legacy R&D institution. A paradigm of excellence in small molecule drug discovery and development.

With this history in mind, let’s consider the lessons that can be drawn from the journeys of Schrödinger and Nimbus.

Lessons From History

One important nugget from this history is that selling software to pharma is really hard. In February of 2020, Schrödinger went public. Thirty years after their founding, we could see their growth. In their S-1, they wrote, “In 2018, all of the top 20 pharmaceutical companies, measured by revenue, licensed our solutions, accounting for $22.0 million, or 33%, of our 2018 revenue.”

This is a solid business. Schrödinger is currently trading at ~$17 a share, with a $1.29B market cap. Building a billion dollar business is incredible, but it’s a far cry from Microsoft’s growth. The company is also a fraction of the size of Vertex, who pursued a vertically integrated model based on similar ideas. Vertex is now worth over $100B.

Schrödinger appears to have arrived at a similar conclusion. Over time, they’ve evolved to partner on drug development programs—which is where the other two thirds of their revenue comes from. In 2018, they also launched their own pipeline of internal programs. It’s hard to imagine that this wasn’t influenced by their experiences with Nimbus. One of their largest revenue windfalls has been the distributions they received from the TYK2 sale.

As “generative AI” comes of age in biology, many new companies are exploring pure software business models to enable broad access to this technology. History would suggest this strategy captures less value—but purely indexing on history is a foolish exercise in technology. Things change! Studying history helps clarify what would need to be different. If we are ever going to see trillion dollar biotech software companies, the predictions they generate will need to be orders of magnitude better than any existing tools.

And what can we learn from Nimbus’s journey?

The company has proven that the combination of computation and experimental out-sourcing can produce real value. Consider their first ACC transaction with Gilead. Reflecting on the sale, Booth shared some impressive numbers:

Using the ACC program as an example, we achieved a bona fide Development Candidate in roughly 2 years and ~$8M from a novel virtual screen hit at an allosteric pocket. We achieved definitive clinical proof of mechanism in our Phase 1b for an aggregate, fully loaded project spend of ~$20M. These metrics for a first-in-class, chemically novel program are impressive by any measure.

Nimbus also proved that the hub-and-spoke model works. They’ve made two major asset sales while remaining intact as a business, a unicorn feat in the world of biotech platform companies.

I shared some of the gory details of their history because it’s important to understand that their success wasn’t pre-ordained at incorporation because of a clever business model. There wasn’t a smooth pre-meditated path from $400M to $4B between ACC and TYK2. Their trajectory required a lot of hard work, guts, and luck.

And while the model has worked, it didn’t work quite the way they’d originally hoped. When their ideas made contact with reality, they realized that they’d have to prioritize getting their Apollo Mission off the ground. This required ruthless prioritization of their best programs, much like any other biotech.

It’s also interesting to reflect on why the Nimbus team is doing this. Reading through their thinking, it feels like a blend of pragmatism and an intense commitment to an aesthetic ideal.

Pragmatically, it’s extremely challenging—and prohibitively expensive—to build a new commercial organization that supports a blockbuster product.

As Keiper put it, “We knew if we were successful in psoriasis, the implications would require a large multinational company to create the value of global registrations in multiple indications. Given the value of established infrastructure in pharma, it was clear that an M&A acquisition of our TYK2 subsidiary was likely.”

This is part of the deep truth tucked behind the centrality of M&A in the biotech industry. As we saw earlier, most of the generational biotechs were built in the 1980s. At this time, it cost much less to independently develop and commercialize new drugs.

Here’s a crucial excerpt from Matt Herper’s excellent piece on the trial bottleneck:

“Certainly the cost of clinical trials has become so outrageous we have to do something to change it,” said George Yancopoulos, Regeneron’s co-founder and chief scientific officer. He remembers that when he started it cost $10,000 per patient to conduct a clinical trial. Now it can cost $500,000, he said. “Just think how expensive that can be. It really limits what we can do.”

This really needs to change. And it can! As far as I know, the laws of physics haven’t changed since trials cost $10,000 per patient. It’s possible.

But faced with the world as it is, the Nimbus team knew they’d ultimately need to sell the assets they developed. The strong aesthetic ideal expressed in the company is the desire to build an enduring “legacy R&D institution” despite this. They didn’t want to be a one hit wonder—they wanted to build something with staying power.

And the shape of that institution is very specifically designed. In Keiper’s words, “Nimbus is committed to the notion that “small is beautiful” in drug R&D: breakthrough small molecules designed by a small expert team.”

The hub-and-spoke model let them express that vision.

As we’ll see over the course of this series, that’s not the only type of business that can be built with this structure. Over the course of Nimbus’s history, they flirted with going public several times. This would have required changing up their corporate structure and winding down the LLC—which legally can’t conduct a public offering.

This isn’t the only possible outcome. BridgeBio and Roivant Sciences, the next companies in this series, are both public hub-and-spoke biotechs. Although all of these companies have structural similarities, they’ve used this business model to solve very distinct challenges.

Next time, we’ll continue our analysis with another case study.

What other types of enduring businesses are made possible with this structure?

Further Reading

This post wouldn’t have been possible without The Book of Nimbus that Bruce Booth, Jeb Keiper, and many members of the Nimbus team contributed to over the years on LifeSciVC. Most of the source links and quotes derive from these materials. If you want to go deeper on this history, I highly recommend studying this team’s writing.

This type of knowledge sharing is incredibly important for our industry. As I support more biotech companies writing the next chapter of biotech history, I hope to pay it forward by sharing more of what I learn.

Speaking of paying it forward, I hope that we can reduce the cost associated with building businesses like Nimbus over time. This business required a lot of legal and accounting work that many founders don’t want to deal with.

How could we make launching a hub-and-spoke platform as easy as using Stripe Atlas?

Thanks for reading the first installment of the hub-and-spoke series. If you don’t want to miss the next chapter, you can subscribe for free to have it delivered to your inbox:

Until next time! 🧬

This is increasingly hard to do. As David pointed out, very few biotechs have successfully navigated this transition since the 1980s.

The Carmot co-founders spun out Kimia Therapeutics, the Prometheus founders launched Mirador Therapeutics, and the Karuna founders launched Seaport Therapeutics.

This is the ballpark. Schrödinger owned 3.8% of Nimbus as of 2022, and Nimbus had raised over $400M. I’m assuming a rough ~60% dilution, but it could be higher, meaning Schrödinger’s initial ownership would have been higher.

The initial name for Nimbus was Project Troubled Water, Inc.

The massive expansion of the CRO industry—including offshore CROs in China—made the entire biotech industry much more capital efficient. Ideas can now be tested without building out an entire lab and R&D organization in-house. The BIOSECURE Act now aims to block the use of CROs in countries that are our “foreign adversaries.” If you’re thinking about ways to build low-cost, tech-enabled CROs in the United States, I’d love to talk with you!

They ultimately received $200M in milestones before the ACC inhibitor missed its endpoints. Drugging a different target (TR-beta) led to the first drug approval in MASH earlier this year.

Elliot, awesome analysis as usual. Thank you.

Where do you see Alto fitting into this model, if at all? Do you think their recent data readout suggest it's their platform/approach that needs work, or just that the specific compound might just not be effective?

Super interesting thanks for going deep. I love the Book of Nimbus concept will dive deep on that!