Hub-and-Spoke Biotechs: BridgeBio

Attempting "Moneyball for biotech"

Welcome to The Century of Biology! This newsletter explores data, companies, and ideas from the frontier of biology. You can subscribe for free to have the next post delivered to your inbox:

What I initially thought would be a summer hiatus stretched into a longer break from regular writing. But I’ve now defended my PhD (🍾🍾) and am excited to have more mental bandwidth for CoB again!

And I’ll have more to share about what I’m doing next… soon. 👀

For now, I’m back with a detailed profile of one of the companies I’m most intrigued by.

Enjoy! 🧬

In 1994, Jeff Bezos left a high-paying job at a Wall Street firm and moved across the country to start an Internet business. In his telling of the story, the logic was quite simple: Web usage was exploding—with 2300% annual growth—and he wanted a piece of the action.1

Clearly, he was directionally right. Amazon is now one of the biggest businesses in the world. The Internet did continue to exponentially grow. But he was also early—early enough that the dot-com bubble, caused by the “irrational exuberance” of other people chasing the same opportunity, was an existential threat to the company early on.

In the aftermath of the bubble, entrepreneurs got back to work discovering every viable Internet business. One interesting visualization of this search process is the saturation of every corner of the Craigslist home page with Internet companies.

Many of these businesses failed, some succeeded, and others succeeded massively. But the search was extensive. Name a sector—any sector—and there are probably dozens of attempts to build Internet businesses within it.

The genomic revolution has gone a bit differently.

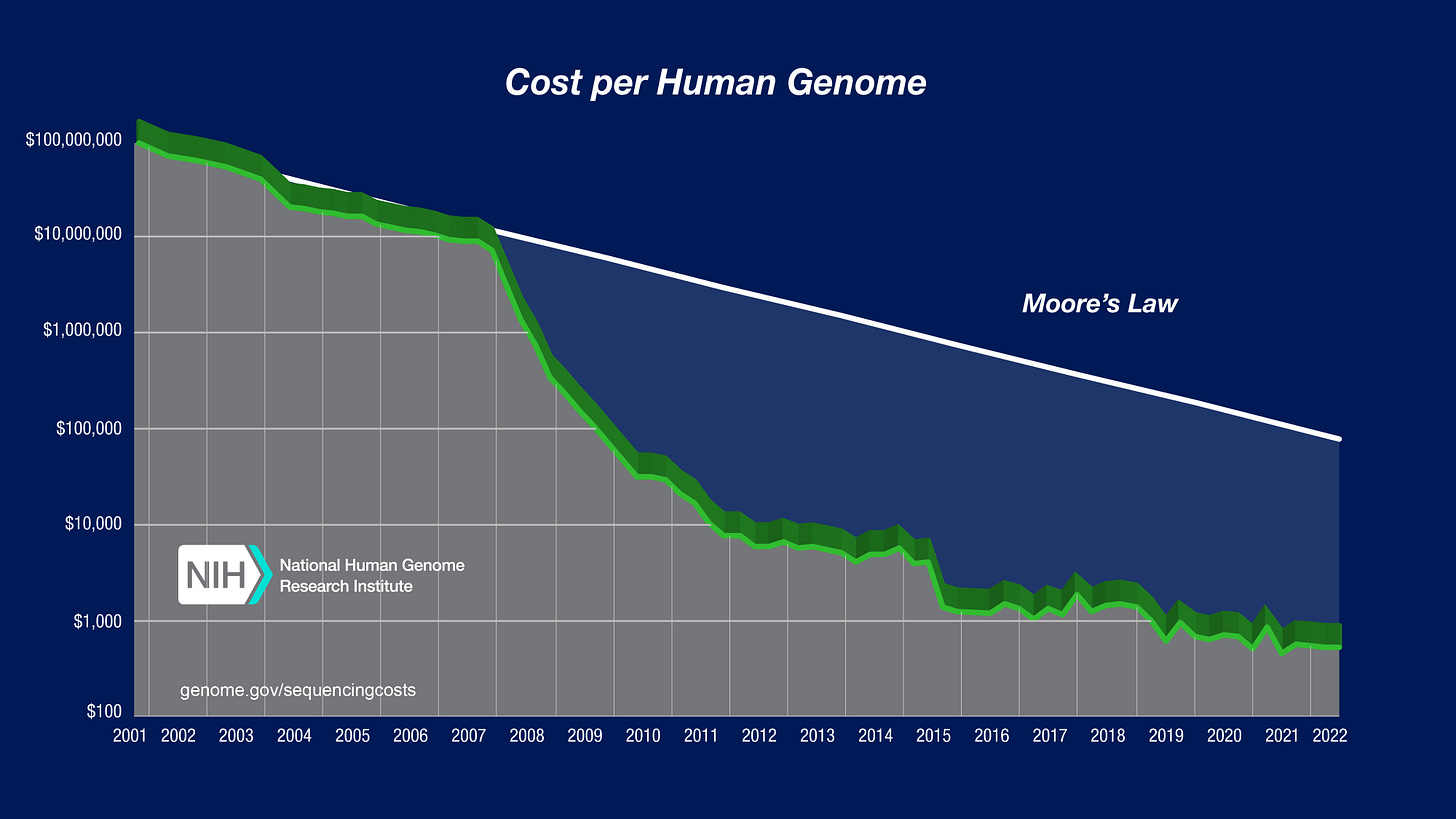

We definitely have our own version of Bezos’s Internet growth statistic: the cost of DNA sequencing has dropped so rapidly that it makes Moore’s Law look linear.

We also had a bubble of “irrational exuberance” from investors followed by deflated hopes. But the cycle following the bubble played out differently. Some very large businesses did emerge from the chaos. At its highest share price to-date, Illumina had a $75B market capitalization. It’s not Amazon, but it’s a very big business—and its growth is evidence of the large-scale adoption of DNA sequencing by research labs and companies all over the world.

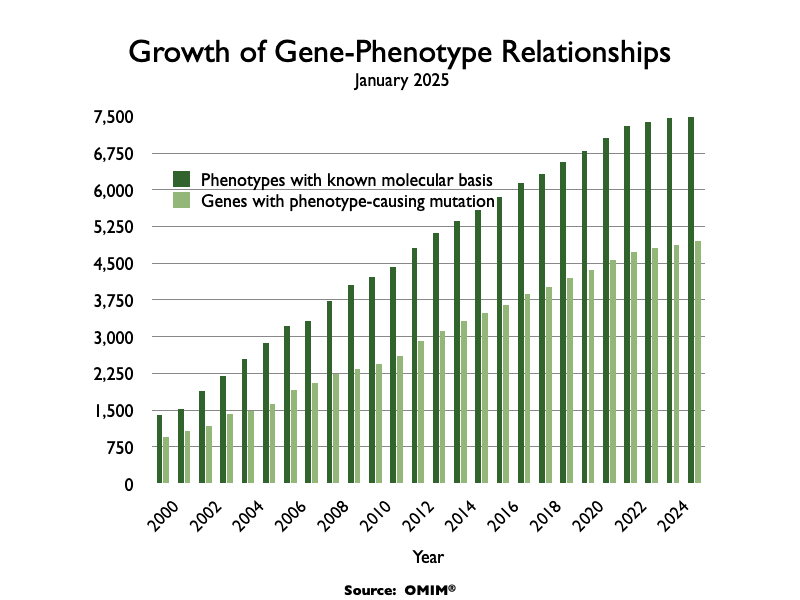

What we haven’t seen is the same type of frantic hunt for every nugget of value that could be commercialized as a result of this enormous secular trend. The set of diseases for which we have a molecular explanation—which resembles the equivalent of the Craigslist homepage for this analogy—has grown far faster than the corresponding set of new drugs to treat them.

I think this partially explains some of the discontent in the scientific community about the Human Genome Project. After billions of dollars that could have been spent in other places, the result is less transformative than initially advertised.2

For technologists who are more accustomed to seeing their discoveries or inventions transform the world more rapidly, this is confusing:

The responses are fascinating. Many scientists will point out the challenges in delivering gene therapy payloads to specific tissues or organs in the body, or the need for more efficient and safer editing technologies. This is all true—and the progress being made on this front is exciting.

But this doesn’t fully explain the disconnect. We now know far more about the genetic basis of thousands of diseases than we previously did. And most of these diseases still have no treatment of any kind—let alone sophisticated gene therapies.

Why is that?

In 2012, a group of economists from MIT proposed an explanation. Led by Andrew Lo, a brilliant financial economist who was one of the earliest people to sound the alarm on the compounding financial risk that ultimately grew into the 2008 financial crisis, the paper was an exegesis on risk in the biotech market.

In their view, the discrepancy between research progress and clinical progress could be explained by “the trend of increasing risk and complexity in the biopharma industry.” Both the science and the process of commercializing the science had gotten a lot more complicated, making returns much more uncertain.

Based on this diagnosis, Lo and his team proposed a financial engineering strategy to pool risk differently, allowing for more capital—and different kinds of capital—to be put to work accelerating biotech progress.

In 2015, a principal at a biotech venture firm called Third Rock Ventures named Neil Kumar quit his job. Kumar could viscerally feel the inefficiencies of the status quo approach to commercializing science. He was determined to test Lo’s ideas. The company Kumar founded is called BridgeBio.

In less than ten years, BridgeBio has launched over thirty drug discovery programs, receiving eighteen INDs and three FDA approvals—an impressive feat by any industry standards. Part of Kumar’s intensity is reflected in one of the company’s central mottos: every minute counts. Patients can’t wait.

Moving at this speed hasn’t always been smooth sailing. Commercially, the company has had a complex trajectory, oscillating between over $10B and less than $1B on the public market.

At the center of BridgeBio’s rapid trajectory is an important business innovation: the hub-and-spoke corporate structure. BridgeBio isn’t one company. It’s an archipelago of discrete subsidiaries—each focused on advancing new therapies for specific genetic diseases.

Here, we’re going to continue our study of hub-and-spoke biotechs by analyzing BridgeBio in detail. This business is based on a fascinating blend of financial theory and cutting-edge genetics. We’ll explore how BridgeBio aims to dramatically accelerate the development of treatments for genetic diseases—and how they could potentially build a generational biotech company by doing so.

Studying BridgeBio is different than studying other biotech companies. It’s an experiment testing a bold financial engineering theory in the real world—in real markets. For current and future founders, investors, or people simply trying to understand the economics of drug discovery, every alignment and gap between the company’s model and reality is a chance to learn something new.

The experiment is continuing as you read this. Kumar and the team are still relentlessly pushing forward. A drug called Attruby—which you’ll hear much more about soon—was approved during the time I was writing this.

Given that BridgeBio is a public company, I want to be very clear about what this post is and is not.

This is not financial advice, I don’t own any BridgeBio shares, and I didn’t receive any compensation from BridgeBio to write this post. My goal is to provide a retrospective analysis of how BridgeBio came to be, and to study their attempt to hyper-scale biotech via financial engineering.

What does it mean to pursue “Moneyball for biotech,” as Andrew Lo would put it?

Can Financial Engineering Cure Cancer?

At a high level, biopharma can seem like a pretty efficient market.

Labs in universities all across the country are constantly producing new research results, and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) funds this work—to the tune of ~$50B a year—with fairly bipartisan support.3 Hundreds of biotech startups are formed every year to commercialize all of this research. The FDA provides a clear roadmap for the development of new drugs. Big Pharma companies buy successful products for billions of dollars—providing a clear path to a return on investment. The result is a continuous stream of new medicines.

This is the Miracle Machine of American biomedical innovation.

As Ben Reinhardt puts it, Health Technology is Weird. Compared to other areas of “deep tech” commercialization, the path from the lab to the market is straightforward.

For most of his life, Andrew Lo assumed pretty much the same thing. But on closer inspection, things were less efficient than they seemed. As he described it, “I started running into more and more examples of amazing medical opportunities that were laying on the shelves because the funding just wasn’t there.”

Beyond anecdotal examples, this phenomenon is numerically apparent. When Lo started asking these questions around 2010, about $48B was spent on biomedical research. Another $127B is spent on clinical development. But only $6-7B was spent on translation.

This translational chasm is called the “Valley of Death” for new biomedical advances.

This observation became the kernel of a new research project in his lab: Lo wanted to understand why this type of funding gap existed.

In his group’s 2012 paper—the same one that would serve as the inspiration for BridgeBio—they proposed an explanation: investing in biomedicine was getting riskier for both scientific and economic reasons.

Scientifically, new therapeutic ideas—like the excitement around precision medicine and the use of molecular biomarkers, or totally new therapeutic modalities like cell and gene therapies—were more complicated. This complexity was a sign of progress, but it also introduced more uncertainty and risk into translation.

From an economic perspective, things were also getting a lot more complicated. They wrote,

A host of economic and public-policy conditions has also contributed to this uncertainty, including declining real prescription-drug spending; rising drug-development costs and shrinking R&D budgets; the 'patent cliff' of 2012 during which several blockbuster patents will expire; increased public-policy and regulatory uncertainty after the Vioxx (rofecoxib) debacle; the potential economic consequences of healthcare reform; less funding, risk tolerance and patience among venture capitalists; narrow and unpredictable windows of opportunity for conducting successful initial public-equity offerings; unprecedented stock market volatility; and the heightened level of financial uncertainty from ongoing repercussions of the recent financial crisis. Consequently, the lengthy process of biomedical innovation is becoming increasingly complex, expensive, uncertain and fraught with conflicting profit-driven and nonpecuniary motivations and public-policy implications. Although other industries may share some of these characteristics, it is difficult to find another so heavily burdened by all of them.

In their view, all of this risk explained the aversion to financing translation. The prospects of success for any single project often seemed far too uncertain to justify investment.

To make investment in translation more compelling, Lo and his team proposed a financial engineering strategy for risk mitigation. Their idea was to pool together a sufficiently large basket of translational efforts such that success at the portfolio level was a statistical certainty.

Would you invest $200M with a 5% chance of hitting the jackpot and getting >$10B in returns for a blockbuster drug? Maybe. But also, maybe not. That’s a pretty low chance for such a big investment.

But if you could find the capital to take that same bet 150 times, your chances of success approach >99%. With a big enough portfolio, the risk profile fundamentally changes.

There was a second critical idea in their proposed solution: the portfolio could be funded with a combination of equity and securitized debt—which is when batches of debt are packaged into a single unit that can be sold to investors.

Why?

As Lo’s team put it,

These two components are inextricably intertwined: diversification within a single entity reduces risk to such an extent that the entity can raise assets by issuing both debt and equity, and the much larger capacity of debt markets makes this diversification possible for multi-billion-dollar portfolios of many expensive and highly risky projects. One indication of this larger capacity is the $1 trillion of straight corporate debt issued in 2011 versus the $41 billion of all initial public-equity offerings (excluding closed-end funds) that same year.

Again, the core idea is to pool risk to make biotech more investable. The decreased risk would open up additional pools of capital. More capital would make even greater diversification possible.

Now, if you’ve ever watched The Big Short, you may be thinking to yourself, “Isn’t this type of elaborate debt packaging exactly the sort of thing that caused the housing crisis?!?!” If you were, you wouldn’t be wrong.

This point wasn’t lost on Lo either—again, he was one of the people raising concerns about these practices years before the financial crisis happened. The authors conceded, “Our proposal is clearly motivated by financial innovations that played a role in the recent financial crisis; hence, it is natural to question the wisdom of this approach.”

But mathematical modeling and simulations seemed to suggest that this idea really did have legs. Based on historical likelihoods of success, they estimated that this basket approach would yield average investment returns of 8.9–11.4% for equity investors, and 5–8% for debt investors.

At a first pass, 5-8% doesn’t seem eye-popping. But for large pools of capital like pension funds that are responsible for investing trillions of dollars collectively, managers shoot for an 8% return rate.

On paper, it seemed like this might actually work!

There was one small problem. The simulations were run with pools of capital ranging from $5B to $15B. Getting to that enticing >99% probability of success at the portfolio level assumed $30B.

That’s a very expensive economic experiment. It’s interesting looking back at the early responses to this paper. The biopharma blogger Derek Lowe covered it with tempered optimism. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery published an article about it as well, quoting many pharma executives and investors who found the thesis compelling.

But expressed interest is a different thing than committed capital.

Leonard Lerer, the co-founder of Innovative Finance, was quoted saying, “it is going to be very difficult for investors to get their heads around it.” Proposing a complex securitization strategy in a complex industry—in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis—isn’t the easiest pitch.

But Lo was insistent that it should be attempted. After publishing another review paper entitled Can Financial Engineering Cure Cancer? he was approached to lead a series of small workshops at MIT called CanceRx. He closed one of these workshops saying, “We have to get some people to step up and actually try this model.”

This message didn’t fall on deaf ears. Neil Kumar was in the audience with his good friend Brian Stephenson. They remember looking at each other and thinking: “Why not us?”

Reduction to Practice

Out of everybody in the audience that day, Kumar had come with a uniquely prepared mind. While earning his PhD in chemical engineering at MIT, Kumar had received some help on mathematical modeling from Andrew Lo and taken a few of his classes.

After MIT, he’d worked in consulting and biopharma business development before taking a job as a principal at Third Rock Ventures. Although Third Rock was one of the most prestigious biotech firms in Boston, he was frustrated. His job was to translate advances in genetic medicine into new companies, but only a small fraction of the promising opportunities were actually being commercialized.

Kumar was a resident of the Valley of Death. Translation was happening, “It’s just that we were doing it so slowly,” he remembered.

So when Lo’s paper on biotech securitization came out, he got really excited. He’d accumulated firsthand experience with the problem that was being outlined. He reached out to Lo to talk about the ideas in more detail, which is how he ended up at the CanceRx conference.

Lo had also invited Stephenson because he thought he’d be uniquely interested in the topic. Kumar and Stephenson were no strangers. After first meeting in their graduate program at MIT, they had started their careers together at McKinsey. Together, they had played around with ideas for using portfolio theory in drug discovery, but none of their biopharma clients had the incentives—or frankly, interest levels—necessary to put the plans into action.

At this point, Stephenson was working at Capital IP, a firm that offers a suite of credit solutions to technology companies for avoiding the dilution of equity financing. His obsession with the intersection of technology and finance had persisted.

After the conference, Kumar and Stephenson got serious about brainstorming how to reduce these financial theories to practice. They’d meet up and work late into the night filling in different pieces of the strategy. As the pieces coalesced, they’d relay their drafts to Lo at MIT—who ultimately joined as a co-founder—and he would send back revisions.

Their goal was to identify a viable model that could start small and scrappy, but had a structure that could compound over time and support an increasingly diversified portfolio.

In other words, what was the minimum viable product for the biotech megafund?

Kumar, Stephenson, and Lo all agreed on one important choice early on: cancer wasn’t the right place to start. Cancer trials are expensive and have the lowest success rates in all of drug discovery. Importantly, from the perspective of portfolio theory, it’s hard to de-correlate the trials when they are all targeting variations of the same underlying disease process. A big component of portfolio theory is that the basket of bets should be as statistically independent as possible.

Lo and his research group had already started to model out a different therapeutic area: orphan diseases. Defined as diseases that affect less than 200,000 individuals in the United States, orphan diseases were consistently overlooked by pharma companies in the era where most blockbusters came from new medicines for common diseases with large patient populations.

This all changed in 1983 when the United States passed the Orphan Drug Act (ODA) into law. Blending a combination of research grants, tax credits, and an expedited regulatory process, the ODA sweetened the pot for drug developers looking to treat these rare diseases.

In addition to the increased commercial viability, both the molecular biology and genomic revolutions dramatically increased the scientific viability of treating these diseases. Around 80% of orphan diseases have a genetic basis. As measuring DNA became cheap and ubiquitous, the number of diseases with a clear molecular explanation exploded.

By 2024, the main database tracking genetic diseases had nearly 7,000 entries where the root cause was well understood.

This scientific revolution explains the chart we looked at earlier:

This opportunity was an ideal fit for a portfolio approach for several reasons. In theory, each disease has a distinct underlying mechanism, making each trial much more de-correlated compared to focusing on cancer. Importantly, drugs supported by human genetic evidence have much higher success rates, with Mendelian diseases caused by a single gene having the highest success rates in the entire industry. As Kumar frames it, genomics has turned treating these diseases into an engineering problem, not a science problem.

The major bottleneck was attracting enough capital to scale translation for thousands of diseases where each individual program still came with non-trivial risk. It seemed like the perfect proving ground for Lo’s megafund strategy.

This all sounded great—until it made first contact with reality. Building a fund was challenging for a few reasons. First, without a track record, raising enough capital to truly test the portfolio approach would be near impossible. (Even with a track record, ~$15-30B is a lot of money!) Second, it would be difficult to guarantee success in the ten year window typical of funds. Third, and perhaps most importantly, the most talented scientific minds he was recruiting wanted to make medicines—not just invest in them.

As every great entrepreneur does, he quickly iterated.

Instead, Kumar proposed building a company. More specifically, a holding company that owned and operated a portfolio of biotech firms making medicines for specific genetic diseases.

In other words, a hub-and-spoke biotech. This solved a bunch of problems. Now, BridgeBio could scale in a stepwise fashion, building up subsidiaries over time. Much less capital would be needed upfront. But over time, the central holding company could still issue debt because of its diversified portfolio. They could also recruit top talent into the subsidiaries, offering both equity and the freedom to drive progress on their programs.

It was a plan to build the megafund “from the bottom up,” as Kumar framed it in one of his early brainstorming emails. With the revised focus from cancer to genetic diseases and the transition from fund to company, all of the core ideas for BridgeBio were in place. It was time to build.

Still, doing new things is really hard.

At this point, Kumar had quit his job at Third Rock and was actively pitching the idea to prospective investors and employees. He was met with a giant wave of rejections—including from Third Rock. “There’s a lot of excitement after you quit your job to be an entrepreneur—and then you go out to pitch your company and you get punched in the face about 8,000 times,” he said.

Kumar wouldn’t stop. As Marc Andreessen once wrote, “The world is a very malleable place. If you know what you want, and you go for it with maximum energy and drive and passion, the world will often reconfigure itself around you much more quickly and easily than you would think.” By throwing himself at the problem with full force, Kumar found that doors started to open.

Reaching Scale

Once the strategy for BridgeBio was clear, they could focus on conversations with the most compatible investors. Biotech VCs still didn’t get it—they wanted a more traditional asset-centric approach. But Kumar was able to convince two successful businessmen, Peter Feinberg and Seth Merrin, to become the company’s first investors.

As they refined and simplified the value proposition, private equity (PE) firms and hedge funds became interested. While PE firms typically shied away from underwriting therapeutic risk, the diversified hub-and-spoke model was uniquely appealing. Kohlberg Kravis Roberts (KKR), an enormous New York–based investment company with over $500B under management, became BridgeBio’s first major investor. Soon after, Perceptive Advisors, a famous biotech hedge fund, also invested.

It was 2015, and BridgeBio finally had $40M to start assembling their portfolio. What should they prioritize first? Inspired by Strategy: A History, a 768 page opus by Lawrence Freedman, a famous Oxford war historian, Kumar felt the company needed a crystal clear objective. He jotted down a simple closed-hand formula and set of principles that would become BridgeBio’s objective function to this day.

They would prioritize the rapid development of genetic medicines with beautiful mechanistic science supporting their development. One of the first major opportunities that fit this objective was acoramidis, a small molecule medicine for transthyretin amyloid cardiomyopathy (ATTR-CM) being developed by a small company called Eidos Therapeutics.

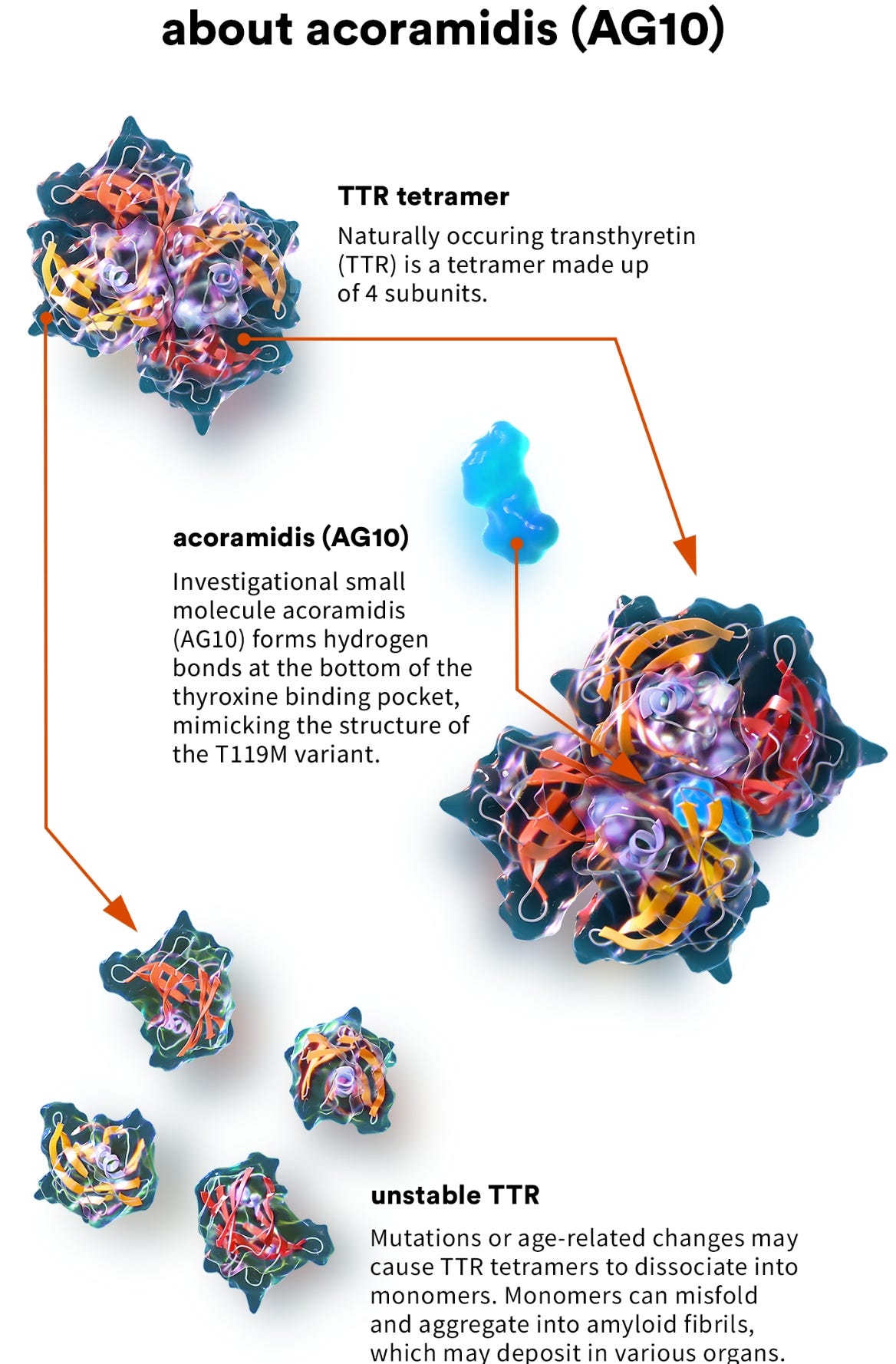

ATTR-CM is a hereditary disease of the heart. After years of basic research, the underlying biology of ATTR-CM is well understood. The disease is caused by a mutation of the transthyretin (TTR) gene, which encodes a transport protein that is responsible for shuttling two molecules—thyroxine and retinol—to the liver.4 When mutated, TTR, which typically self-assembles into a complex consisting of four identical subunits (a homo-tetramer) becomes mis-folded and accumulates in the heart. This accumulation can ultimately lead to heart failure.

Acoramidis works by re-stabilizing the TTR complex, mimicking a known protective genetic variant for ATTR-CM. It’s a case of clear, beautiful science.

In 2016, BridgeBio decided to acquire Eidos and re-launch it as a subsidiary within their hub-and-spoke umbrella. Emphasizing speed—which was baked into the company’s objective function—they designed the Phase 1 trial for acoramidis to evaluate safety and early signals of efficacy. They quickly read out a positive Phase 1 result and financed the Phase 2 study, which again proved to be successful.

Outside of Eidos, the entire company started to gain steam. Several more rounds of private financing had brought in over $400M—with commitments from top tech investors like Sequoia as well as from blue-chip biotech investors and PE funds. The story was resonating. They had used this capital to pick up several more promising assets—both from academic labs and from large pharma companies like Novartis. As long as the genetic evidence was clear, the source—or even the drug modality—didn’t matter.5

At this stage, it was time to go public. There was a slight problem with this. If you’ve been reading along in this hub-and-spoke series, you may remember that Nimbus Therapeutics has remained private. One reason is that an LLC can’t be publicly traded.

BridgeBio wanted access to public equity markets, but wanted to retain the hub-and-spoke model. Looking for solutions, they considered going public via a special purpose acquisition company (SPAC), which is when a public shell corporation acquires a private company. This was in vogue in 2019, but came with drawbacks.

Instead, they performed some corporate jiu jitsu and reorganized the company for a traditional IPO. By tucking the LLC into a traditional corporation, they could pursue a public listing without canning their portfolio model.

With this maneuver complete, they were ready for the public market. And it turned out that the public market was very much ready for them as well. In June of 2019, BridgeBio offered just over 20 million shares at a price of $17 per share. With additional investment from their syndicate, they brought in just over $400M in new capital, making their IPO the largest of the year—and one of the largest biotech IPOs of all time. By the end of 2019, the share price had climbed to over $40, giving BridgeBio a market capitalization of over $4B.

At this point, BridgeBio was approaching $1B of capital raised. But to truly reach scale for their portfolio model, they knew they would need to realize Lo’s original model of tapping into debt financing in addition to equity financing. (Remember, in 2011 there was $1 trillion of corporate debt issued, compared to $41B raised for IPOs.)

Using their original simulations, they made the argument that despite being a pre-revenue biotech company—which is normally an extremely risky investment—their portfolio model gave the company a fundamentally different risk profile. Debt investors ran the models and bought the argument.

In March of 2020, BridgeBio levered up with $550M in debt in the form of a convertible note with a 2.5% interest rate. This is a form of debt where investors are paid interest over time, but the major incentive is the potential for conversion of debt into equity at a premium after a specified period of time. Normally, the term is five years, but BridgeBio was able to negotiate a seven year term to ensure time for more clinical readouts.

Next, BridgeBio raised another convertible note—this time with an eight-year term—for a whopping $750M at a 2.25% interest rate. This officially tipped the scales: by 2021 BridgeBio had raised a multi-billion dollar war chest, with the majority coming in the form of debt rather than equity financing.

Still, Kumar and Stephenson were wary of being undercapitalized to fully test their portfolio theory in the event of initial failure. The first readout for their Phase 3 trial of acoramidis was a month out. If the readout was negative, it could tank their ability to finance the rest of their pipeline. Effectively treating “debt as insurance” against this scenario, they raised $750M in additional debt, with $450M coming up front and $300M delayed until they had clinical readouts.

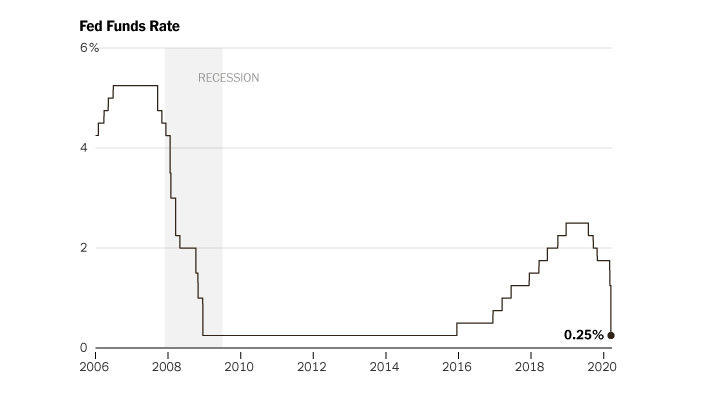

This was a total historical anomaly for two reasons. First, debt providers aren’t running around issuing massive chunks of capital to clinical-stage biotechs with no products. The ability to raise this debt was a testament to the belief in the fundamentally different risk profile afforded by diversification. Second, all of this lending took place at the absolute peak of the debt market driven by COVID-19.

What does that mean?

The spread of the pandemic distorted the market. Some companies saw massive growth—like video conferencing software and at-home exercise equipment—while other businesses saw customer demand disappear overnight. This type of distortion can lead to massive unemployment and cause big economic issues. So in response, the Federal Reserve slashed interest rates—even more steeply than during the 2008 financial crisis—to effectively make it cheaper to borrow money.

When interest rates are low, “safer” investments like government bonds are far less attractive because of their relatively low yields. So with the big drop, managers of big pools of money were suddenly incentivized to look elsewhere—which ends up moving a lot more money into debt markets.

I’m spelling all of this out to highlight the absolutely incredible timing for BridgeBio.

A company that was predicated on a strategy of raising debt found themselves—almost overnight—in a market with cash sloshing around in search of new opportunities to buy corporate debt. I obviously wasn’t in the room, but you can imagine Kumar and Stephenson hunched over their desks, furiously modeling how to best capitalize on this insane opportunity.

Right after this debt spree, the door swung shut. The Federal Reserve began to aggressively hike rates again and money flowed back into government bonds. But Kumar and Stephenson already had secured over $2B in debt capital to fortify against any hiccups in their clinical progress.

Little did they know that they were in for much more than a small hiccup.

The Acoramidis Saga

In the original simulations of Lo’s megafund strategy, the duration of each trial was observed to have a strong impact on performance—with faster trials delivering better returns. Optimizing for speed, the Phase 3 trial for acoramidis had an unusual structure. The readouts would come in two distinct phases: “Part A” and “Part B.” The first primary endpoint was improvement on a test of how far patients could walk in six minutes after a year on the drug. A year and a half later, the rate of mortality and cardiovascular hospitalizations would be assessed.

In 2021, two days after Christmas—and a month after issuing debt—the first endpoint for acoramidis read out. It was negative. There was no significant improvement on the walk test. BridgeBio’s shares immediately cratered to a third of their price.

Now, the portfolio model would be stress tested like never before.

On paper, the megafund model assumed nearly perfect conditions. First, get a mountain of cash up front. Next, check back in fifteen years after you’ve run your basket of de-correlated trials. Profit!

Of course, reality is much less rational.

BridgeBio is a public company whose valuation is contingent on market narrative. The huge swing after the first readout revealed a critical discrepancy between how the company was internally computing its own valuation and how the market was actually valuing it. In the eyes of public investors, most of the value could be attributed to future sales of the company’s lead asset—much like how any other biotech is valued. A missed endpoint threatened those future prospects.

To make matters worse, the entire biotech sector was getting crunched. Because biotech is so capital intensive, the sector trades inversely to interest rates. When cash becomes expensive, biotech stocks get punished.

Kumar and Stephenson battened down the hatches and did everything they could to weather the storm. To extend runway, they rapidly reduced the BridgeBio workforce by 30%. Internally, they worked to re-emphasize the importance of their mission for patients. The worked needed to continue.

They pulled every possible lever to stay lean. To avoid the additional costs of building out their commercial organization in this environment, they found external partners for Nulibry, a drug they had gained FDA approval for in 2021. The priority review voucher this approval brought in was sold off.

But all of these efforts paled in comparison to one simple fact: their war chest of very favorable debt from the prior year gave them sufficient runway to let their “beautiful science” speak for itself.

In March of 2023, a positive Phase 2 readout for infigratinib, another medicine in their pipeline, nearly doubled their share price to $18, roughly the value offered at their IPO. This gave the company a chance to scoop up $150M via a public offering to prepare for more upcoming readouts.

Finally, the moment of truth was around the corner.

BridgeBio braced for the Part B readout of acoramidis in July of 2023. The stakes couldn’t have been higher. Despite their portfolio approach, it had become clear a second failure could pose an existential threat to the company’s future. They’d taken a big bet on this program, having gone as far as using some of their debt to reacquire outstanding shares of Eidos. At the same time, the possible upside from approval had become even more clear.

A lot had happened since BridgeBio first scooped up Eidos in 2016. In 2019, Pfizer gained approval for tafamidis, which became the first drug on the market for ATTR-CM. In 2023, tafamidis delivered $3.3B in sales. As better diagnostics for the disease become more widely used, Global Market Insights estimated that the ATTR-CM could grow to $11.2B by 2032.

All of a sudden, BridgeBio’s pursuit of beautiful science had positioned them to compete for a slice of a fast-growing blockbuster market. Companies like Alnylam and Intellia were also hot on their heels with genetic medicines for ATTR-CM. The pressure was on!

On July 17th in 2023, the company hosted a call with investors to share updates on the results of the Part B readout for acoramidis. The drug appeared to be a decisive success, delivering positive readouts for reducing heart-related hospitalization events (50% relative risk reduction), survival (25% relative risk reduction), and even the 6-minute walk test that initially was negative. The drug also appeared to more effectively stabilize TTR when compared to Pfizer’s tafamidis.

The market responded.

BridgeBio’s share price jumped back to over $30. In November of 2024, after a tumultuous journey, the company gained approval for acoramidis (now marketed as Attruby), triggering evolution towards becoming a full-fledged commercial organization.

BridgeBio’s Current and Future Potential

Having gained three FDA approvals in only ten years, BridgeBio’s track record inspires confidence that they are capable of efficiently translating genetic insights into new medicines. But efficient R&D doesn’t always equate to efficient commercialization.

And making this transition is really hard. According to McKinsey, only 20-30% of first-time commercial organizations manage to exceed their launch expectations, whereas 40-50% of established organizations do so. Because of this, companies can find themselves in a “second valley of death,” where existing investors want to sell their shares to realize profits from clinical success before anybody else wants to step up to invest in a potentially risky new product launch.

This has been particularly acute for BridgeBio. Early on, analyst projections for Attruby were so low that Kumar pointed out they were effectively predicting “the worst second-mover launch of all time.” In typical Kumar fashion, he was undaunted by the challenge, saying, “There’s probably a degree of skepticism around ‘can a bunch of science nerds launch a drug’? I get that, and I’m going to show that we can do that.”

So far, that’s exactly what they’ve done. Kicking off 2025 at the JPM Healthcare Conference, BridgeBio announced that Attruby has already been prescribed over 400 times, providing evidence for adoption from the medical community—and for BridgeBio’s ability to deliver on it. Some analysts have now taken note and updated their forecasts with more optimistic projections.

But for BridgeBio to truly live up to Lo and Kumar’s initial vision, success can’t be measured by a single product launch. Successes will need to compound, snowballing into a giant diversified portfolio. To truly satisfy their objective function, they’ll need to translate genetic insights into approved drugs at a rate that requires adding an asterisk to charts of yearly approval rates to explain the leap in volume.

This year will be another important stepping stone towards that goal. The company is anticipating three distinct Phase 3 readouts in the second half of the year. If successful, the BBP-418 and Encaleret trials would deliver the first approved therapies for patients with the genetic diseases they target. The Infigratinib trial would deliver the first oral therapy for children with achondroplasia.

Kumar and the team continue to tweak and refine the hub-and-spoke model. While debt investors underwrote the portfolio approach in 2020 and 2021, it’s become clear equity investors are still wary. Most of BridgeBio’s current value is attributed to Attruby’s future revenue streams. To keep funding early R&D efforts while commercializing Attruby, BridgeBio spun out two new subsidiaries in 2024, BridgeBio Oncology and GondolaBio, attracting $500M in fresh capital from top investors.

It will be fascinating to see what comes of the relationship between the parent company and these subsidiaries over time.

Our industry is currently in flux. The American Miracle Machine has produced some objectively extraordinary results, but is clearly not perfect. The existing system is facing wholly new challenges, both internally and externally.

In the midst of all of this change, BridgeBio is running a fundamentally unique experiment. Grounded in first principles thinking, they are challenging existing assumptions around nearly every aspect of biotech financing and development.

Clearly, not every aspect of the new model has worked like they thought it would on paper. But new medicines are making their way to patients at an extraordinary rate. And each hurdle has provided valuable lessons for both the company and the rest of the sector.

In some ways, the BridgeBio experiment is like a health checkup for biotech. Every gap between the original “frictionless” megafund theory and the realities of the market can help diagnose why more drugs aren’t getting to patients faster.

And we need to keep testing creative ideas to solve these problems. Because as Kumar emphasizes, the patients can’t wait.

Sources and Further Reading

This was a particularly challenging company to write about. While I did my best to cover the most critical aspects of BridgeBio’s origins and journey so far, I had to omit a lot of interesting details.

I’m grateful to Neil Kumar and Anthony Bogachev at BridgeBio for talking with me and offering support in my research process.

If you want to go deeper, here are some particularly valuable resources:

Commercializing biomedical research through securitization techniques — the original research paper that spurred the development of BridgeBio.

Applications of Portfolio Theory to Accelerating Biomedical Innovation — a brilliant academic paper written by Neil Kumar, Andrew Lo, Chinmay Shukla, and Brian Stephenson detailing the company’s history from the perspective of the founders. This was one of the most valuable sources I came across.

BridgeBio S-1 — a snapshot of BridgeBio’s state at the time of IPO. It also includes more details about how they took a hub-and-spoke company public.

From Aha Moment To $10 Billion Biopharma — a nice profile of BridgeBio’s early history that I pulled several quotes from.

Select coverage of the Acoramidis Saga:

Earlier drug approvals that I didn’t cover:

Challenges with reacquiring Eidos that I didn’t cover:

Eidos Reportedly Received $4.6 Billion Takeover Bid From Glaxo

BridgeBio Wins Appeal Over Eidos Deal, Ending Pension Fund Suit

tldr: it doesn’t really benefit shareholders to sell off a valuable spoke and have all of that cash sitting on the balance sheet of a public company. This is a big difference when considering the strategy and corporate structure of Nimbus and BridgeBio.

Thanks for reading the second installment of the hub-and-spoke series. If you enjoyed this, considering reading the first chapter about Nimbus, another fascinating hub-and-spoke company.

If you don’t want to miss the next chapter, you can subscribe for free to have it delivered to your inbox:

Until next time! 🧬

This epic 1997 interview is worth watching at some point.

Personally, I think this is totally wrong. But maybe that’s an analysis for a future post!

Seemingly until recently. It’s still too early to fully understand the impact of the recent attempts to slash NIH indirect costs or whether they will actually go into effect. This type of abrupt change could grind America’s Miracle Machine to a halt—which seems like a pretty bad trade for saving $5B annually. Indirect costs are a real problem that scientists have advocated against for years, but punching >$100M holes in the annual budgets of our nation’s top research institutions overnight doesn’t seem like the right solution.

Fun fact: the name stands for transports thyroxine and retinol.

Getting this part right is far from guesswork. BridgeBio has entire teams, including a division of Computational Genomics, dedicated to evaluating promising new opportunities.

excellent review. topic, content and balance of detail/macro context. catchy reading w enough cookies to follow various rabbit holes… 🕳️

Great to have you back! Fantastic essay describing a complex company. Can’t wait to read what is next in your queue!