On biotech platform strategy

Thoughts and updates on platform typology and partnering dynamics

Welcome to The Century of Biology! This newsletter explores data, companies, and ideas from the frontier of biology. You can subscribe for free to have the next post delivered to your inbox:

Enjoy! 🧬

For biotech founders and investors, not all types of risk are the same. Opinions vary, but three major buckets of risk are scientific/technical risk, team/execution risk, and market risk. In other words, how likely is it that the technology will actually work, does the company have what it takes to make it work, and if it does work, will anybody actually pay money for it?

In biopharma, the prevailing sentiment is that scientific/technical risk is the dominant bucket. We know that markets can be massive—medicines can scale to billions of patients a year with an initial branded monopoly. Teams often have decades of experience, frequently having earned terminal degrees for research that made them world experts in their focus area. The looming challenge is that biology is profoundly complex, and clinical trial success rates are in the single digits.

In reality, market risk in biotech is very real. Differences in business development strategies can lead to dramatically different commercial outcomes, and can even be the deciding factor between success and total failure—especially for platform companies that intend to develop more than one medicine.

For these companies, there are perennial questions about how to effectively sequence internal pipeline development and external pharmaceutical partnerships, what types of co-development agreements will capture the most value, and even what corporate structure best fits their underlying technology.

Today, we’re joined by Patrick Malone, who is a physician-scientist, a talented investor at KdT Ventures, a good friend, and the first ever co-author for a Century of Biology post. Through deep historical analysis of companies, research for early-stage biotech investments, and countless long conversations, we’ve both tried to develop guiding frameworks for biotech platform strategy.

Now, we want to share some of those learnings with you.

Here’s what we’re going to cover:

A distillation of the key insights from Steven H. Holtzman’s writings on early-stage biotech value creation. First published five years ago, this gem of biotech strategy writing has played an important role in shaping both of our views on platforms and partnerships. Holtzman introduces a useful typology of platforms that provides a valuable foundation for further analysis.

An updated placement of therapeutics platforms within the broader landscape of biotech business models.

Re-analyzing biotech dogma that services platform companies eventually become vertically-integrated therapeutics platforms, with some data to suggest that this trend may soon change.

Upfront, we have a caveat. For such a complex and important topic, we have more questions than answers. Rather than pronouncing the discovery of a universal platform playbook, we are open-sourcing the tools and mental models that help us understand the broader evolution of biotech.

We hope this essay adds to your own cognitive toolbox, and serves as the starting point of an important conversation. Please let us know what you don’t understand, what you think we got wrong, and what we’re missing!

With that being said, we’ve got a lot of ground to cover. Let’s jump in! 🧬

Early-stage biotech value creation

In 2018, biotech veteran Steven Holtzman was deep in the idea maze. As the President and CEO of Decibel Therapeutics—a gene therapy platform company that was ultimately acquired by Regeneron—he needed to develop a coherent business strategy. To do this effectively, he decided to zoom out and study the broader history of biotech successes and failures.

Thankfully for us, he took things one step further. He shared his “typology” of biotech platforms in an epic blog post packed with historical and operational insights, “philosophical musings” (courtesy of his previous life as an Oxford-trained philosopher), and strategic ideas—as well as a dialogue with several biotech luminaries about the proposed framework. One observation sits at the core of this post:

All platforms make multiple products, but not all platforms do it in the same way.

Obvious, right? But the devil is in the details. Of course different platform companies will use different technologies—that’s not the point here. The key realization is that over the course of biotech history, we’ve used the term “platform” to describe two different types of companies: those with core technologies centered around new therapeutic modalities (think antibodies, different RNA medicines, cell therapies), and those focused on new therapeutics insights (via genetics/genomics, high-throughput screening, or other new data generation strategies).

Let’s start on the far left of this tree. Many companies in biopharma are incorporated to develop and sell a single drug asset (or small handful of drug assets) based on academic results. While nothing in the business of making drugs is easy, there is a clear playbook for value creation for product companies.

In the trade-off between raising capital by selling company equity (i.e. dilutive VC funding) and financing development via partnerships (i.e. non-dilutive pharma co-development) in exchange for rights to future profits, the clear choice is to avoid selling away rights to the drug too early. All of the value for the drug candidate—and ultimately the entire company—exists in those future profits. The goal is to sequentially raise equity-based capital at higher valuations based on clinical milestones before the most realistic (and frequent) exit strategy: getting bought by a pharma company for your asset.

All platform companies (the right side of the tree) start on a fundamentally different premise. Platforms are launched to commercialize biotechnologies that hold the promise to produce multiple products. Genentech wasn’t founded to commercialize a molecule from an academic lab; it was launched to industrialize recombinant DNA (rDNA) technology. The number of medicines that could be produced based on this single modality is enormous.

Given this potential “embarrassment of riches,” new modality platforms have different strategic considerations for financing compared to pure product companies. In theory, the future value of the company is distributed across all of the potential assets. This makes early partnerships—even with worse terms—more appealing. The logic is: “Sure, let’s partner on this first program, there’s more where that came from.”

This dynamic can create a powerful flywheel, giving companies capital to finance more platform development and advance their next assets farther on their own before partnering again. Wash, rinse, repeat. Ultimately, the endgame for modality platforms is to capture the most possible value by developing an internal pipeline of assets in addition to external partnerships. (We’ve devoted an entire section to the dynamics at play here—but hang with us for now for the rest of the typology.)

Okay, what about for platform companies that produce insights rather than modalities?

Consider Millennium Pharma, one of the first and most successful genomics platform companies. Millennium didn’t focus on any specific therapeutic modality like rDNA for Genentech. Instead, they used the power of high-throughput genetics and adjacent technologies to produce new disease insights—such as information about molecular pathways and potential drug targets within them.

For a company like Millennium, the partnering logic is similar to that of a modality platform. Unlike a company focused on a single product, it makes more sense to partner early and often to avoid raising dilutive capital. Millennium did this masterfully. With only $8.35M of VC dollars, Millennium managed to land several massive partnerships and go public. After a careful sequencing of partnerships and internal asset development, Millennium was ultimately acquired by Takeda for $9B—representing a 100x multiple in the share price from the initial financing.

Awesome! Just land massive partnerships, create internal assets, and profit, right?

There are several major caveats to consider for insights platforms. First, the pharma appetite for your insights is a function of how much of a technological step-change they are. Millennium was building on top of a historical advance, not an incremental improvement. Second, as Holtzman frames it, “The history of data in the biopharmaceutical industry is the history of its commoditization.” Just consider the subsequent price decline in sequencing. Pharma companies make their money from products, and are strongly incentivized to disintermediate any partners who provide them information rather than new drugs. As a result, the transition towards vertical integration (through an internal pipeline) needs to happen much more quickly.

Finally, not all insights platforms are the same:

Holtzman further delineates the insights platform “genus” into two distinct “species.” First, there are platform companies with a technology that has broad applicability to many different biological pathways and drug targets—like Millennium with genomics. Second, there are platforms with a deep disease-specific focus. One of the most successful examples is Agios, which primarily focuses on metabolic insights into cancer.

The narrower the focus for an insights platform, the more its strategy starts to resemble a product-focused company. There are less “shots on goal,” so each one needs to count. As a result, they realistically need to land a sizable multi-target “foundational corporate partnership” earlier on—like Agios did with Celgene—and then push even harder to advance their own internal programs.

Okay, that’s the typology. Like all lessons from the field of Strategy, this is more of an overarching model of the different possible paths to value creation than a drag-and-drop playbook. Each success story contains real nuance. As Holtzman framed it in response to a comment from Mark Levin, the CEO of Millennium and a founding partner of Third Rock Ventures, “In reality, using large partnerships to create out-size value requires a keen sense of the external partnering environment, identifying the potential partner(s) which at that specific moment in its/their history has/have come to perceive a critical need for what you have, and crafting deals in which you, while you sell rights, retain the potential for value creation by, for example, retaining ownership of the knowledge. That, not a cookie-cutter model, is your legacy in this arena.”

Still, it’s worth internalizing the fact that the contours of your technology will dictate your partnering strategy.

Where platforms sit in the biotech landscape

The increasing digitization of biology has drawn the attention and money of more tech-focused founders and investors—a trend that people refer to as TechBio. This has led to some confusion, because people in tech use the term “platform” in a way that differs from how traditional biotech investors use it. For example, the prolific tech entrepreneur and investor Elad Gil has spelled out his own tech platform typology that includes software infrastructure companies like Stripe, suites of apps and developer APIs like Meta, and operating systems like Microsoft.

Clearly, we all seem to be intent on making the word “platform” do as much work as possible.

So, by the tech definition, isn’t a company like Illumina a platform company? Jeff Tong, a partner at Third Rock Ventures, actually argued for this in a response to Holtzman saying, “Illumina arguably is the most successful pure-play “Platform” company in a long time (that also interestingly isn’t forward-integrating into therapeutics).”1 For Holtzman, Illumina isn’t a platform, it’s something else altogether. He responded, saying he would “suggest that Illumina is an equipment (and related reagents) company.”

We would agree. At the risk of being pedantic, let’s make this distinction even more explicit. In biotech, the most horizontally integrated businesses that make tech people want to scream “Platform!” are actually tools and hardware businesses—with scientific software also occupying this niche—that we like to call infrastructure/services companies. Somewhere in between infrastructure/services companies and full-blown therapeutics platforms are a set of companies that broadly partner with pharma and have no aspiration to develop their own internal pipelines. These can be thought of as hybrid services platforms.

Here’s what this looks like graphically:

Historically, a vertical focus on internally developed drugs has been the most successful value creation strategy in all of biotech. While moving new medicines into the clinic isn’t for the faint of heart, the potential upside for patients, inventors, and investors is enormous. This strategy works. Still, services/infrastructure companies often don’t get the credit they deserve. Some of these companies have reshaped entire fields of science and achieved massive financial success.

Services platforms have a more complicated track record. There is a delicate dance between the desire to keep the virtuous cycle of partner revenue running indefinitely, and the pressure to consolidate resources into internal programs for maximal value creation.

To unpack this, we’ll examine some of the historical comparisons between these business models, how the current market is shaping these decisions, and how the evolution of biopharma might ultimately flip things upside down.

Most services platforms eventually become therapeutics platforms (for now)

Building a services platform in biotech, which exclusively pursues external partnerships with no internal pipeline, is really, really hard. In his original essay, Holtzman observed that only Ionis and Genmab stand out as examples of companies that have successfully scaled this model.

As John Maraganore pointed out in a reply to Holtzman, the relative valuations and share prices of Ionis and Alnylam—another leader in RNA interference that took a more vertical product-focused approach—reflect that even the most successful services platforms “leave a ton of value on the table.” While Ionis has expanded to pursue their wholly-owned clinical programs, Alnylam did so much earlier—which in part explains the discrepancy in company size below, despite both focusing on highly similar technology.

The challenge is that 1) the probability of success of clinical trials is so low that drug development is primarily about the quality of programs (and luck being on your side!), not quantity, and 2) there are limits to how broadly applicable a single platform or technology are across therapeutic areas or programs, limiting the total addressable market. Since the publication of Holtzman’s essay, only a few services platforms stand out (e.g., AbCellera, Adimab, Alloy, Dyno Therapeutics).

The most recent example demonstrating the challenge of this model is Atomwise, one of the prototypical AI-driven drug discovery companies. Atomwise has pivoted from partnerships to internal programs, their CEO noting that “it’s tough to get [a services platform] as a business to work in pharma.” If the first law of biotechnology is that every tools or diagnostic company eventually becomes a therapeutics company, the second law might be that every services platform eventually becomes a therapeutics platform with an internal pipeline.

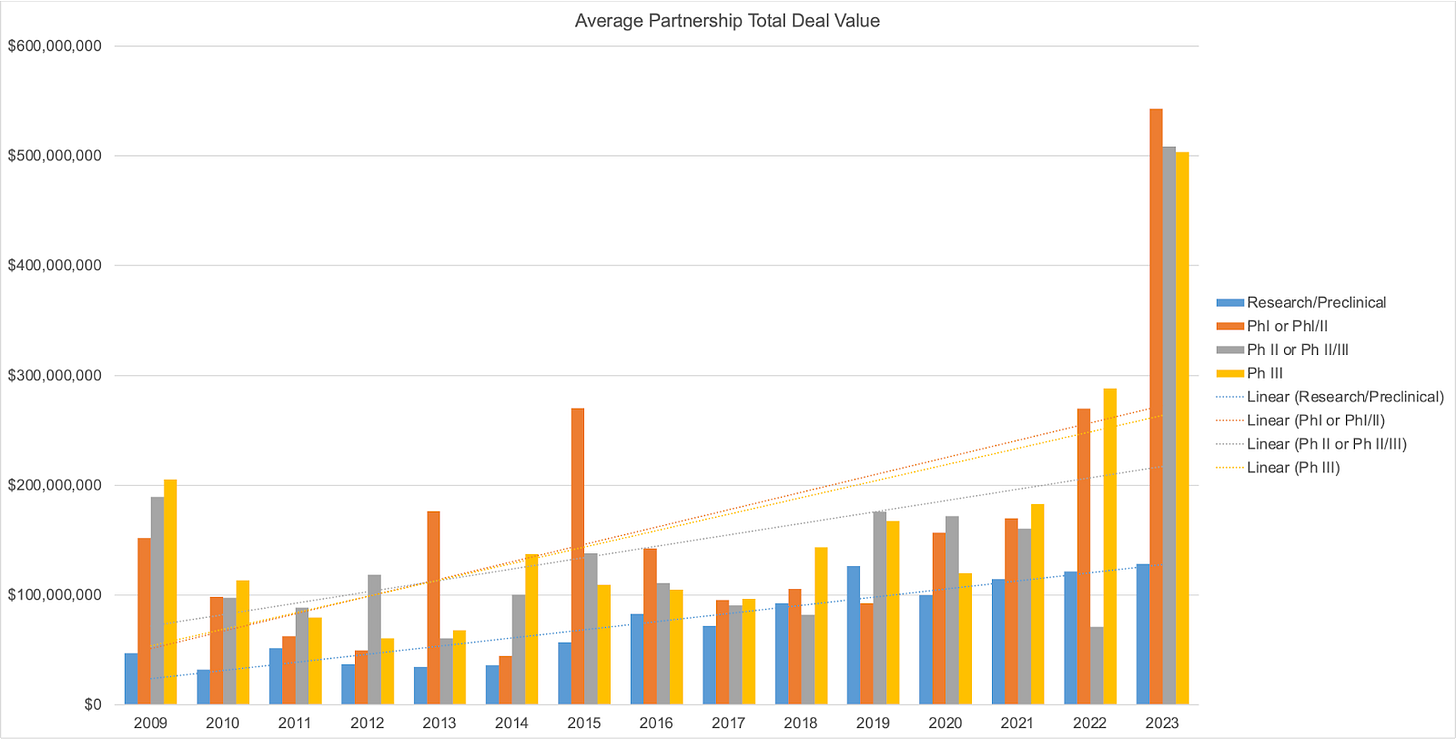

But as early-stage investors, we must always challenge dogma. Partnership-centric models in biotech have been difficult to scale historically, but will this continue to be true in the future? We took a data-driven approach to address this question, and analyzed all biopharma partnerships from 2009-2023 with disclosed terms in the BioCentury database, totaling over 2000 partnerships across all development stages. Our logic was as follows: if platform technologies (e.g. AI, novel delivery modalities, etc) are becoming more proven and validated, and biotech companies are consistently delivering value to pharma partners, average partnership deal value should increase over time.

Further, if average deal value continues to increase, at some point it will be feasible (and even preferable) to pursue a services/partnerships-only model as a platform biotech.

As technologies developed by platform biotechs become more critical to large pharma’s ability to develop novel drugs, and as large pharma invests less in internal R&D and outsources more to external partners, pricing power may shift to platform biotechs.

In the figure below, the data show that there is a trend towards increasing average partnership total deal value since 2009 across the research/preclinical stage and Ph I-III. These data are adjusted for inflation (we’re no economists, but normalizing each year’s CPI to the CPI in 2009, the first year in our analysis, seemed reasonable).

One potential issue with analyzing total deal value is that the trend could be driven by the increased capital expenditure and R&D costs associated with newer generations of biotech platforms (often reflected in larger upfront payments), which wouldn’t necessarily reflect a shift in pricing power and in who (biotech vs pharma partner) is capturing more value in the partnership. To control for this, we also analyzed average milestone payments over time. Milestone payments are a better proxy for the value of the underlying asset. Similar to total deal value, there is a trend towards increasing average milestone payments over time.

Finally, we observed a positive trend in the number of biopharma partnerships each year, effectively increasing the total addressable market (TAM) for services platforms—which is the product of the total number of deals, and each deal's respective value.

To be clear, these data are noisy, and there are a bunch of potential confounding variables. Our intention in this analysis is not to be overly quantitative, but rather suggest a qualitative trend towards increasing TAM for services platforms. There is also the possibility that some of the trend is driven by 2023, where COVID revenues and capital inflows from the biotech bull market of 2020-2022 resulted in an outlier year for partnerships.

To address this possibility, we excluded 2023 from an analysis of average total deal value and milestone payments (averaged across asset stages), shown in the figure below. The weak positive trend seems to hold up even when excluding 2023.

Taken together, increasing partnership value and deal volume over time suggests that there is a shift in pricing power from partners (often large pharma) to technology platform developers (often small/mid-size biotechs). If this trend continues, external partnerships as a mechanism of value capture will improve relative to wholly owned internal programs, thus improving the scalability and success-rate of services platforms in biotech.

Final thoughts

While biotech platforms have produced massive societal and financial value, navigating decisions between partnerships and internal drug development is nontrivial. We believe that young technical founders are uniquely positioned to build and lead the next generation of massive platform companies. In order to achieve this future, as a community we need to stand on the shoulder of the giants that came before us.

We need to be students of history, refining our business strategies based on a deeper shared knowledge of past successes and failures. To avoid falling into the trap of tribal dogma, we need to pair these insights with forward-looking data-driven rigor. As a starting point, we can observe:

All platforms make multiple products, but not all platforms do it in the same way.

There is a lot to be learned from Holtzman’s thoughtful typology of platform companies. The central technological focus of a company—whether it is pioneering new modalities or biological insights—plays a key role in shaping partnering and commercial strategy. The specific nuances of the typology and its impact on business development are meant to serve as a guiding cognitive framework rather than as an off-the-shelf playbook. Building a generational business will always be more art than science.

As we’ve seen, the pharmaceutical landscape is in flux. While historical wisdom would indicate that wholly-owned drugs are the best way to produce enormous value, the evolution of the broader pharma landscape may change this in the future. If pharma continues to outsource R&D, leading to a continual increase in partnering deal values, we could see the emergence of the first wave of truly generational services platforms.

There are countless ways that technological innovation could shake up the current status quo. Here are just a few examples:

What happens if modalities become increasingly commoditized?

Already, we’ve seen that pharma outsourcing has provided a fertile ground for the emergence of massive CROs and CDMOs like WuXi Biologics, Samsung Biologics, Evotec, and countless others. This trend has led to a wave of virtual biotechs that can produce molecules rather than insights without ever running their own lab.2

Holtzman argued that insights companies deal with unique challenges given “the fact that the output of the Genus 2, Species A Platform Companies is information/insights, NOT, as with the Genus 1 Platform Companies, New Chemical Entities (NCEs) and biologic therapeutics.”

In the limit, what if this ceases to be true? What if tech-enabled CDMOs, rather than big pharma companies, ultimately have the best infrastructure for making medicines? What does the Atomwise of 2040 look like? Can we ever reach a point where we have a sufficiently broad suite of services platforms for producing arbitrary modalities that the balance shifts in a dramatic way towards new insights?

What if clinical development and commercialization are democratized?

Vial and many other companies are working hard to dramatically lower the capital intensity and time associated with testing as many medicines as possible in the clinic. What if other companies emerge that make it easier for small startups to become independent businesses that manufacture and commercialize their own medicines? This would represent another massive shift in the current balance of power when negotiating partnership agreements with Big Pharma companies, providing another tailwind for an increase in deal value over time.

Clearly, nothing is set in stone. What we hope to provide here is a set of strategic considerations for the biotech platforms of the future. A lot will change, we have a lot to learn, and we’ll be wrong more than we’ll be right.

We hope this is the start of a dynamic conversation for our community, rather than a static decree.

How do you think the next massive biotech platforms will be built?

A massive thank you to Steven Holtzman for open-sourcing some of his hard-earned wisdom, to Patrick Malone for joining us and sharing his insights, and to Cain McClary for his careful read that made this piece much stronger.

If you don’t want to miss upcoming essays, you should consider subscribing for free to have them delivered to your inbox:

Until next time! 🧬

I am struck by the assumption that the final output of all biotech companies is a drug. While this is basically true if you look in the rearview mirror, I think drugs will make up a shrinking percentage of the value created by biology in the coming decades. Everything in the natural world is made by biology, and as we stumble around learning how to design biological systems, we will be able to create a much wider range of valuable end-products than therapeutics alone.

Great post - but I think you'd need to normalize each year's inflation based on the cumulative inflation for all previous years going back to 2009, not just normalizing each year directly to 2009. This is because I assume the annual CPI prints you found were comparing inflation year on year, not to 2009.

Probably won't make a huge difference though.

Loved the analysis otherwise!