Compounding Until Inflection

Present vs. future platform value

Welcome to The Century of Biology! This newsletter explores data, companies, and ideas from the frontier of biology. You can subscribe for free to have the next post delivered to your inbox:

Enjoy! 🧬

It’s hard choosing between present and future value. Would you pick one marshmallow now, or two if you wait? This type of question is what sits at the core of the perennial product vs. platform debate in biotech—it’s just drugs instead of marshmallows.

Opinions swing dramatically based on market conditions.

When conditions are favorable, investors extend their time horizons. With a decade of 0% interest rates building to a climax of accelerated biotech investment during COVID, money was poured into moonshot platforms. When the tide went back out, some of these companies were the farthest from the shore. All of the value was in the future.

When this happens, biotech investors become pessimistic about the possibility of building generational companies. Public markets value positive clinical results—everything else is a rounding error. Every result is one step closer towards cash flows from a drug, or more realistically a pharma acquisition. The goal is to drive towards present value.

I say when this happens, because it’s cyclical. In an interview in 2012, the biotech veteran Steve Holtzman expression his frustration with the “continued pessimism about the possibility of building great companies that are sustainable as opposed to merely short-term plays which can make money for investors.” It’s the same phenomenon. He was just talking about the previous market downturn.

What does it take to build a sustainable company?

All value comes from clinical products. But it’s only possible to build a generational biotech company with a foundational technology platform capable of developing multiple products. This is why The Column Group—one of the best performing biotech venture firms of all time—invests in “unique scientific platforms” based on their “potential to deliver multiple breakthrough therapeutics.”

Great platforms require big ideas and long-term thinking. It isn’t possible to build a company like Genentech, Regeneron, Vertex, or Moderna without both ingredients.

Each of these companies used strategic pharma partnerships to scale. Partnerships are a way to trade some future value in exchange for near-term sustainability. As Steve puts it, “You need to use equity capital, but you also need to use pharmaceutical partnerships where they are your near-term market. You’re selling things that are on the way to product, or technology that they wish to access.”

But it’s important to avoid selling away too much future value.

Let’s look at an example. In a previous post about platform strategy, Patrick Malone and I compared the growth of Ionis and Alnylam over time. Both companies focus on developing medicines that target RNA rather than proteins, using different types of short RNA molecules instead of small molecules. This is a really big idea—it’s a radically different approach to drug development.1

While both companies had clinical success, Alnylam is now much bigger. One major reason is that Ionis partnered away more of their products, while Alnylam aggressively forward integrated to commercialize their own drugs more quickly.

In their 2012 10-K filing, Ionis described their model, saying “Our strategy is to do what we do best—to discover unique antisense drugs and develop these drugs to key clinical value inflection points. We discover and conduct early development of new drugs and, at the key clinical value inflection points, out-license our drugs to partners.”

Alnlyam was thinking about things differently. In their filing for the same year, they said “Our core product strategy, which we refer to as “Alnylam 5x15,” is focused on the development and commercialization of novel RNAi therapeutics for the treatment of genetically defined diseases with high unmet medical need. Under our core product strategy, we expect to have five RNAi therapeutic programs in clinical development, including programs in advanced stages, on our own or with one or more collaborators, by the end of 2015.”

Empirically, Alnylam’s concentrated strategy has captured more value so far.

But history isn’t a perfect predictor of the future. There’s a chance that this lesson may not generalize to biotech platforms focused on compounding data and machine learning advances. These companies have a different trade-off between present and future value to consider.

What are the defining characteristics of this type of company?

As defined by Jacob Kimmel, a co-founder of NewLimit, this new “species” of biotech has three primary traits:

Builds an In silico Model of the biological process sufficient to predict the effect of changes to key engineering parameters

Collects & curates a Data Corpus describing a biological system more completely than ever before

Generates value from the model by Predicting and Validating useful modifications to a biological process to make it faster, cheaper, or more effective

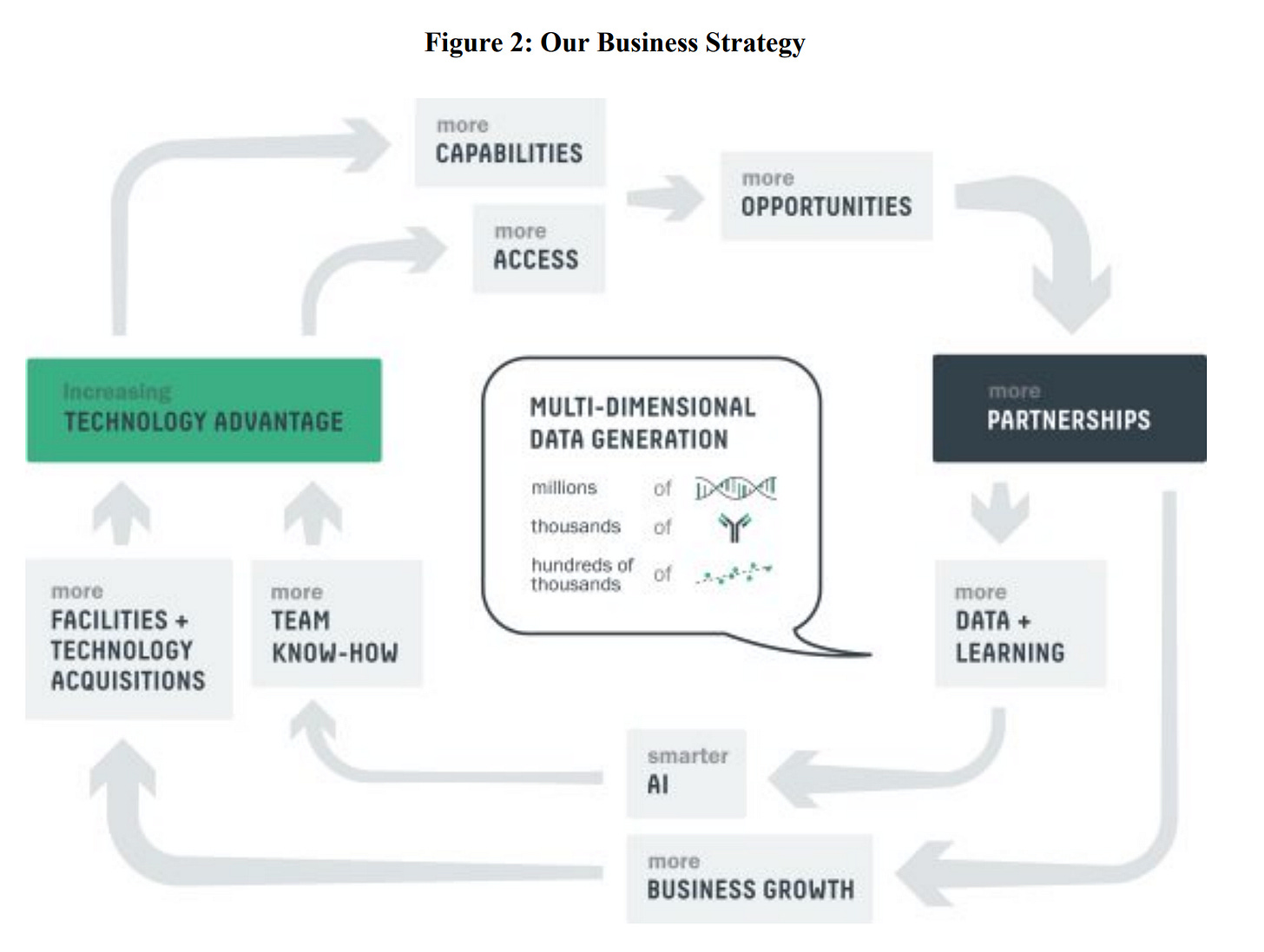

In this framing, partnerships have a different impact. Historically, partnerships have been viewed as selling away future value to gain present value. In theory, if a platform’s value compounds over time with data, a partnership creates near-term value and makes future programs more valuable by increasing the likelihood of future success.

If this is the case, a business model that more closely resembles Ionis may be the right starting point. By focusing on partnerships, a data-centric company is effectively being paid to compound.

One example of this strategy in practice is AbCellera. Founded in 2012, AbCellera focused on building an antibody discovery engine and making it broadly available to partners. All the way up to their IPO, there was no internal pipeline. Instead, they had 94 discovery programs with 26 different partners.

Unlike nearly every other biotech, AbCellera was cash flow positive early on. In their S-1 filing, they said “Our business has historically been both high growth and capital efficient. Revenues have grown at a 109% CAGR since 2014. We have generated positive operating cash flow cumulatively since our inception in 2012 and in every year since 2018.”

While the core engine was compounding, they avoided forward integrating towards developing an internal pipeline. After nearly a decade of steady growth, the COVID pandemic sparked a major inflection point. AbCellera quickly launched efforts to develop antibodies to neutralize SARS-CoV-2. And just as quickly, they had their first results.

With a single sample from a COVID patient, AbCellera became the first company in the world to identify a monoclonal antibody targeting the virus.

Only ninety days later, Eli & Lilly dosed the first patients with this antibody in a Phase 1 trial. With an acceptable safety profile, it was granted an emergency use authorization (EUA) by the FDA and marketed as Bamlanivimab. Over 700,000 COVID patients were dosed with Bamlanivimab over the course of the pandemic.

Without a pause, AbCellera used their platform to discover a next-generation SARS-CoV-2 antibody. Again, it was granted an EUA and marketed by Eli & Lilly. In a statement, Carl Hansen, CEO of AbCellera, said “The discovery of two authorized therapeutic antibodies within a year of each other demonstrates the power of our platform, and its potential to quickly generate best-in-class therapeutics for our partners.”

After COVID vaccines hit the market, the emergency authorizations for the antibodies were revoked just as quickly as they were granted. The massive revenue spike came and went. But AbCellera was left in an interesting position.

After the pandemic, AbCellera had their discovery engine and over $1B in cash. With this foundation, they moved into the last phase of their platform buildout by investing in “manufacturing, regulatory, and clinical capabilities.”

As their platform build nears completion, AbCellera is starting to advance an internal pipeline of antibody drugs. They aim to file their first two IND submissions by 2025. As they put it, “We are evolving into a vertically integrated biotech.”

To be clear, none of this is investment advice. This is a thought experiment about the compounding value of platforms, and AbCellera is a really interesting example. By broadly partnering instead of immediately building an internal pipeline, AbCellera was able to invest in a decade of technology development with impressive capital efficiency. Now, they’re evolving to keep growing.2

What if AbCellera—or another company with this strategy—starts to produce differentiated products at a rate that no other company can keep up with? This type of technological inflection point hasn’t happened for biotech yet. But reasoning by (very) loose analogy, we know that sustained platform investment can lead to massive growth. Consider NVIDIA’s trajectory.

At NVIDIA GTC this year, Jensen talked about the early years of the CUDA platform for GPU programming, which has been instrumental in their rapid growth. He said they thought the project would be “an overnight success” back in 2006, and that “almost twenty years later it happened.”3

In their long journey through the desert, NVIDIA was busy making machines that make their machines. They were refining their simulation software and design tools. They were laying the foundation for GPU programming.

Now, they have a massive technical lead that will only be overcome by another technological paradigm shift.

Maybe this is why Jensen is so excited about “digital biology,” as he calls it. He’s survived a twenty year platform buildout that ultimately transformed his industry. Maybe he thinks this new wave of tech-centric bio companies could do the same.

This is effectively making the TechBio worldview as explicit as possible. It’s a belief that technology can transform drug discovery. From that perspective, the logical choice is to invest in sustained technology development long enough that this bet pays off in a big way. Everything else would be a rounding error.

Achieving that may require a creative business model and partnering strategy. A technology company needs to be able to keep compounding despite market fluctuations and binary clinical readouts. AbCellera was founded in 2012—the same year that Holtzman expressed his frustration with the industry’s short-term thinking.

But it didn’t matter, and that’s the point. They were able to stay cash flow positive while building towards vertical integration with their engine over time.

The goal is to continue compounding until inflection.

Thanks for reading this essay about long-term platform strategy. I’d like to thank Patrick Malone, Pablo Lubroth, Michael Fischbach, and Packy McCormick for their conversations and feedback on these ideas.

One quick note: the annual SynBioBeta synthetic biology is coming up fast. This year, it will be May 6-9 at the San Jose Convention Center in California. SynBioBeta has been a great supporter of this newsletter (to be clear, not a sponsor!), and is offering a $200 discount for readers who use the code centuryofbio when registering. If you join, feel free to reach out and say hi!

If you don’t want to miss upcoming essays, you should consider subscribing for free to have them delivered to your inbox:

Until next time! 🧬

Ionis focuses on antisense medicines, which are short oligonucleotides with reverse complementarity to a targeted messenger RNA molecule. Here’s the vision in the words of the founder: “With antisense drugs, we understand the forces that result in binding selectively to RNA receptors (Watson-Crick base pairing), so antisense-based drug discovery has proved to be much more efficient and less costly than traditional drug discovery. Because members of the same chemical class of antisense drugs have the same basic properties, my experience is that their behavior has proved to be more predictable than that of small molecules, resulting in a lower failure rate in early development. These factors coupled with shared manufacturing and analytical and formulation processes result in dramatic improvements in efficiency.”

Alnylam develops small interfering RNA medicines, which recruit the RNA-induced silencing complex to targeted messenger RNA molecules to degrade them. Based on similar logic to antisense medicines, development is much more predictable. Alnylam’s clinical success rates are incredible.

Expanding the number of cell types and types and tissues targetable by RNA medicines is a massive opportunity.

It’s worth stating the bear case here. After the huge drop-off from the COVID revenues, AbCellera’s stock has been in a landslide and lost over 90% of its value. None of the AbCellera-discovered antibodies that its partners have advanced to the clinic so far are particularly jaw-dropping. These factors have made some investors very skeptical. As the trajectories of companies like Ionis and Adimab show, this type of out-licensing model can be a very slow burn. Maybe in this specific scenario, part of the evolution is in response to market pressure to grow faster.

This type of growth trajectory presents a challenge for venture capitalists who are expected to deliver returns to their limited partners (LPs) on a ten year time frame. If Sequoia distributed NVIDIA’s shares to their LPs after the IPO, it wouldn’t have been a particularly impressive investment multiple. But for anybody that held onto these shares for long enough, it would have produced a fortune. Apparently Sequoia partners Mark Steven and Mike Moritz never sold their shares. Back of the envelope math would suggest this delivered a >100,000x multiple on their initial Seed investment.

This is an incredibly well-written piece, excellent job.