Going Founder Mode On Cancer

Sid Sijbrandij's extraordinary care journey

Welcome to The Century of Biology! This newsletter explores data, companies, and ideas from the frontier of biology. You can subscribe for free to have the next post delivered to your inbox:

Today, we’re going to study Sid Sijbrandij’s incredible journey to cure his own cancer.

Enjoy! 🧬

Sid Sijbrandij is an information maximalist.

On October 14, 2021, GitLab, the business he had started in his upstairs home office in the Netherlands only ten years earlier, went public. GitLab started as an open-source collaboration tool for software developers. Sid led its transformation into a massive application that tracks every stream of information in the software development lifecycle.

GitLab makes a great product. Businesses of all sizes use it. But GitLab is arguably best known in the business community for something else: it is one of the largest fully remote companies in the world. With over 2,500 employees and a $6.4B market capitalization, they still don’t operate a single in-person office.

Achieving this required doing things differently. One example is a cultural norm that Sid refers to as “radical transparency.” Consider the GitLab Handbook. Now totaling over 3,000 pages, the handbook is a central repository (updated and maintained with GitLab’s own version control system) for every piece of company information you could imagine. Not only is it available to all employees, it is publicly hosted on the World Wide Web for all to see.

Sid developed a complex information processing system (GitLab’s unique operating culture) to scale the development of a complex information product (GitLab) built for creating and maintaining complex information products (software).

It’s safe to say that Sid really likes information. But on November 18, 2022, Sid got information that absolutely nobody wants.

He had cancer.

Sid had a lot to lose. At this point, he was a self-made billionaire entrepreneur who was happily married to his life partner of over 25 years. Suddenly, the six centimeter mass growing out of his upper spine threatened to end all of that.

Throughout 2023, Sid dutifully underwent a brutal care regimen that he can only describe in retrospect as “devastating.” His tumorous vertebrae was surgically removed and his spine was fused with a titanium frame. He underwent rounds of radiation and chemotherapy so intense that four blood transfusions were required to keep him alive.

Despite all of this, his cancer resurfaced in 2024. Sid says the message he got from his physician was basically, “You’re done with standard of care, maybe there is a trial somewhere, good luck!” But that wasn’t going to cut it for Sid. He wanted to live.

So he decided to go founder mode on his cancer.

Over the last two years, Sid has assembled a veritable SWAT team to navigate—and in many cases create—his care journey.

Many of the ingredients resemble GitLab.

The top layer of his care stack is a system of intensive information gathering and documentation that is not dissimilar from the GitLab Handbook. In a massive Google Doc entitled “Sid Health Notes,” he and his team compile detailed entries for every medical interaction or meeting with a cancer researcher or oncology company they take. The document has grown to over 1,000 pages for just 2025.

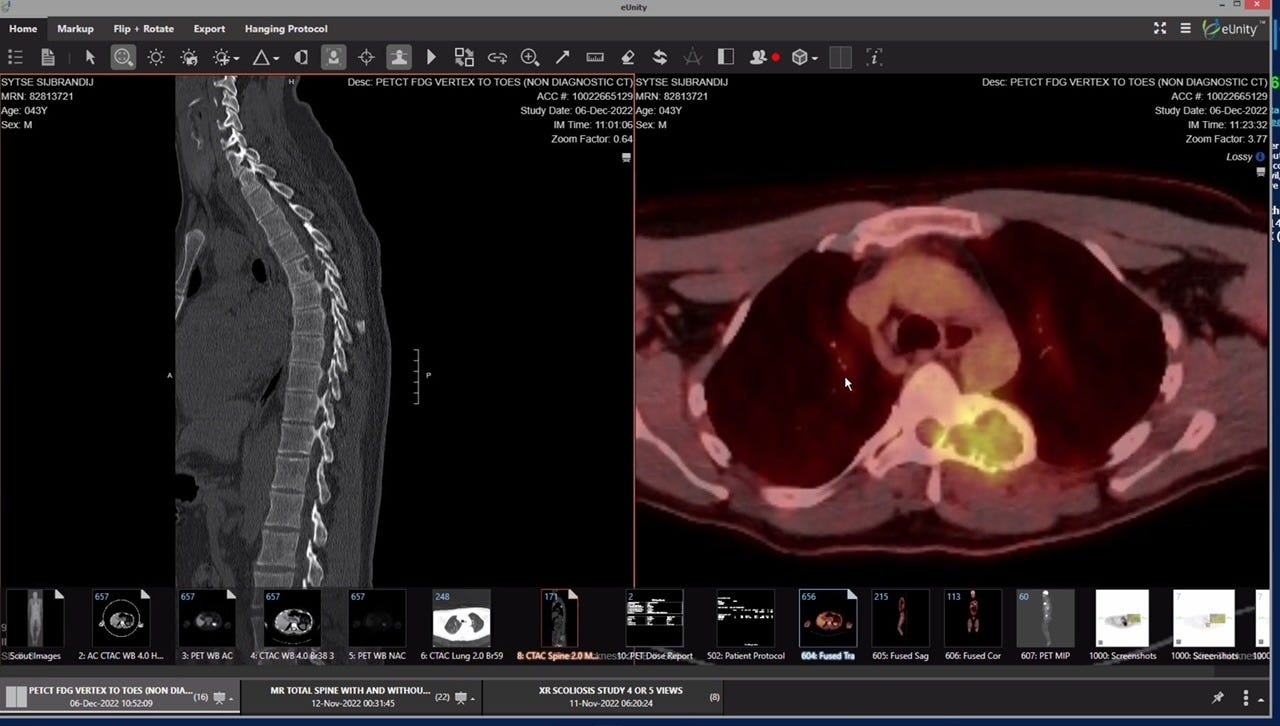

Hyperlinked within this Doc is the next part of the stack, which Sid refers to as “maximal diagnostics.” The raw data for every lab test, scan, and genomic sequencing result is meticulously stored. And there are a lot of results. “I’m doing every diagnostic I can get my hands on, and doing them often,” he says.

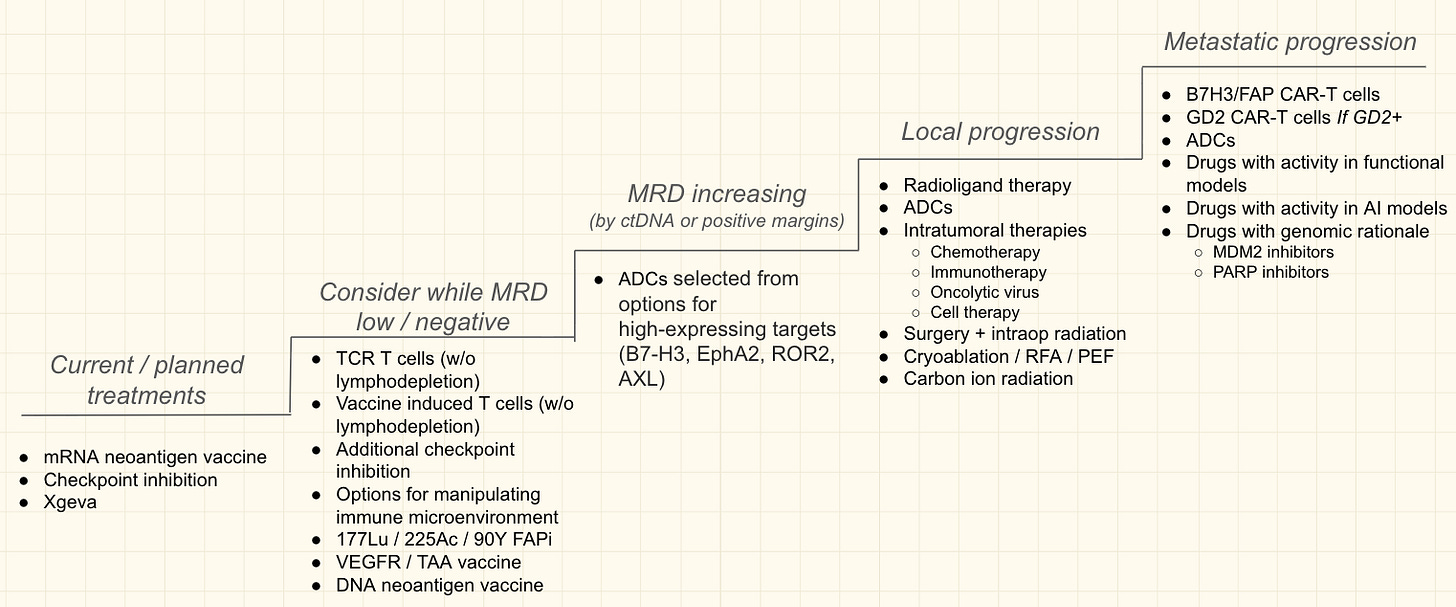

The final part of Sid’s care stack is the actual set of therapies he can take. After exhausting his options with the standard of care, he set out to create his own “therapeutic ladder” of possible treatments. Some rungs on this ladder are existing medicines that could potentially be repurposed from other cancers based on information gained from diagnostics. Others are individualized therapies designed in collaboration with researchers or companies specifically for Sid.

Sid developed a complex information management system (his care notes) to manage streams of complex information (his diagnostics) that guide the use and creation of complex information products (drugs).

Cancer is a disease of information. Loss of genomic information threatens to destroy the self. It may have met its match with Sid.

So far, the results of this regimen have been nothing short of extraordinary. Sid’s cancer is in remission. He has enough energy that he decided to start another software company, called Kilo Code, all while running a venture capital fund, a charitable foundation, and traveling the world with his wife.

Sid is very clearly an anomalous person. The approach to his care and the results are equally anomalous. A simplistic takeaway from this story could be, “Wow! A brilliant billionaire seemingly cured his cancer. Good for him!”

But as I’ve gotten to know Sid, it’s become abundantly clear to me that there is more to the story than that.

First off, his story serves as an existence proof of what is possible.

There hasn’t always been a better tier of healthcare available to the wealthy. As an extreme example, consider the British royal family, who for centuries experienced dramatically higher infant mortality rates than ordinary people living in the rural countryside. Greater access to healthcare was a bad thing.

But sometimes, better care is available. One example is Magic Johnson’s story. When he announced that he had contracted HIV at the height of his legendary basketball career, people mourned like he had just told the world he was going to die. Because at the time, HIV was practically a death sentence. But through a combination of early detection, new breakthrough treatments, and a strict diet and fitness regimen, Johnson is alive and thriving. His HIV is now undetectable.

This proved to be an early indicator of a dramatically improved treatment paradigm for HIV. While he likely benefited from exceptional care and medical access at the time, these treatments are now much more widely available. It was a case where “the future is here, it’s just not evenly distributed,” as William Gibson famously put it.

Sid’s story also reveals lessons about the barriers that limit our ability to reimagine cancer care.

Even with extraordinary resources and motivation, Sid has faced major obstacles at every turn. He still struggles to gain access to his own tissues and order diagnostics. When advocating for more aggressive treatment, he has had to contend with a system that equates the Hippocratic Oath of “first do no harm” with a lethargy that can feel like “first do nothing,” in his view.

But a rigid healthcare system hasn’t been the only bottleneck. There are also structural challenges with how drugs are discovered and developed. And in some cases, even with how drugs are defined.

In recent years, China has adopted a dramatically different posture towards testing experimental medicines that now threatens the future competitiveness of the American biotech sector. This has reopened the debate within the biotech industry about what evidence and standards should be required to test and approve a new experimental medicine. It currently costs far too much.

Most of this conversation centers around a scientific and regulatory paradigm where medicines have one chemical recipe that is given to all eligible patients. But with new technologies, it is increasingly possible to consider making bespoke therapies tailored for an individual patient. Researchers and patients have pushed the FDA to reconsider its regulatory stance towards these types of personalized therapies.

As Sid puts it, “It costs $1B to get a drug approved. But it costs $1M to dose a single person [with a personalized therapy]. That discrepancy is the highest it’s ever been. And it keeps growing because it keeps getting easier and easier to make new medicines while the cost of the Phase 3 keeps going up.”

Drug discovery has gotten less efficient over time despite extraordinary technological progress. There is now intense pressure to do something about that.

Considering these massive tailwinds, Sid’s story may be a harbinger of what’s to come rather than a curious human-interest story about one billionaire’s medical luck.

That’s the story we’re going to explore here.

Chapter One: “It Became My Own Job to Keep Myself Alive”

Sid has always loved to build things. After studying engineering physics and management science at the University of Twente, he took a job in 2003 at a small Dutch firm called U-Boat Worx that specialized in building personal recreational submarines.

He worked closely with the founder, Bert Houtman, who had taken an interest in “private submersibles” after a successful career as a software entrepreneur. While Sid loved the engineering challenges, it became clear that the growth potential for this industry was limited. So he started to spend his free time teaching himself the Ruby programming language and scrolling Hacker News.

This website gave Sid a chance to imbibe some of the early Web and startup culture that was forming on the other side of the Atlantic. Paul Graham and his co-founders had just launched Y Combinator (YC) in Cambridge, Massachusetts. YC created Hacker News to curate and discuss interesting links and ideas about technology and business.

After working as a programmer and starting his first startup, Sid stumbled on a Hacker News link that caught his attention. It was about a project called GitLab. Started by a Ukrainian programmer named Dmitriy Zaporozhets, GitLab began as an open-source application for programmers collaborating using the Git version control tool.

According to the GitLab Handbook, “He created GitLab from his house in Ukraine. It was a house without running water but Dmitriy perceived not having a great collaboration tool as a bigger problem than his daily trip to the communal well.”

Sid was excited about the project for a few reasons. First, he thought the Ruby implementation was beautiful code. He also thought it made sense for the source code of a code collaboration tool to be open, meaning that coders could collaborate on making the tool itself better. This was in contrast to other related applications like GitHub, whose source code was proprietary.

But the project was only a repository. If a programmer wanted to use it, they’d need to download the source code and host it themselves. Sid had an idea. He’d create a hosted version of the application called Gitlab.io to solve this problem.

That evening, while making some pancakes for dinner with his girlfriend Karen, he posted a link to sign up for a beta version of this product on Hacker News. While they were cooking, he’d occasionally dash up to his office to check if it was getting any traction. At first, it wasn’t.

And then one time, he didn’t come back downstairs. Karen brought up the finished pancakes and found him absorbed in the comment section of the post. It had made the front page of Hacker News. In the first three hours, over 150 people had signed up for early access. Sid could see the first faint glimmer of product-market-fit.

Next, he sent an email to Dmitriy telling him he was going to make this product. Reflecting a true open-source ethos, Dmitriy’s response was basically, “Great. Thanks for doing that!” And he asked for nothing in return. It was an open project. People could use it as they pleased.

Over time though, GitLab kept gaining traction and Dmitriy decided he wanted to work on the project full-time. Sid jumped at the opportunity and found a way to sponsor him with the proceeds of his tiny bootstrapped company. Eventually, Dmitriy became the co-founder and CTO of the company.

Things started to get more serious. More companies signed up for the service and they iterated on the right commercial offerings to complement the open-source project. And they were accepted into the winter 2015 (W15) batch of YC.

In the following years, GitLab’s growth was dramatic. By 2016, the product had millions of users and the company had raised a $20M Series B. Companies and institutions like IBM, Macy’s, ING, NASA and VMWare were paying enterprise customers.

At the risk of stating the obvious, this was well before the COVID pandemic had normalized remote work. In Silicon Valley, the expectation from investors was that startups needed to work in person. At every stage of growth, Sid heard this opinion.

But Sid prefers to make these types of decisions based on empirical data. He wanted to hire the best people. And the best people weren’t always in the valley. After all, his co-founder Dmitriy was still living in a small village in Ukraine.

Despite the early team’s geographic diversity, they all seemed to work together effectively. In fact, the product they were building was designed to make that possible. Short experiments in establishing an office presence didn’t seem to impact productivity. So they leaned into making the best possible fully remote culture.

Great companies reflect the preferences of their founders. As Guy Kawasaki, Apple’s former Chief Evangelist, put it, “Apple is Steve Jobs with ten thousand lives.” One major preference is how a company communicates. Amazon and Stripe are famous for their internal writing cultures. NVIDIA has a flat organization structure with a large number of executives constantly reporting directly to Jensen.

For Sid and the early GitLab team, it was natural to maintain company information in large wikis much like how open-source projects are typically structured. This became the GitLab Handbook, which is edited and maintained using GitLab itself.

There are simple rules for its use. If any employee has a question about GitLab, they should first consult the Handbook. If there is no answer, they need to ask around to figure it out and then contribute what they’ve learned to the Handbook. It is a collaborative, living document. Over the years, the page count—which is also programmatically tracked and shared within the Handbook—has grown to over 3,000.

As GitLab has grown, they have trended towards even greater transparency and information sharing. The GitLab Unfiltered YouTube channel has now posted over 13,000 videos of internal meetings. Fairly banal recordings of code reviews or explanations of GitLab’s architecture are posted for all to see. There is seemingly no unit of information too small to record and share.

When the world was forced to go remote during COVID, all of GitLab’s geeky quirks and processes became a fascination of the business community. Multiple Harvard case studies were written about the business. Sid became a regular guest on TV shows and podcasts to talk about how to manage distributed teams.

By 2022, Sid was the CEO of a fast-growing public software company. His net worth had surpassed $1B and he was a widely studied and respected expert on remote work. And his long-term girlfriend Karen was now his wife. Things were going pretty well.

And then one day, during his typical workout, he felt a sharp pain in his chest. This wasn’t the first time he’d felt it, so he wasn’t too concerned. Typically, it went away. But this time, it got worse. Two weeks later, he found himself laying awake at four in the morning, still in pain. He decided to go to the emergency room.

After a workup and an X-ray, he was sent home. Later that morning, his doctor gave him a call and asked, “Do you know how to meditate?” His blood pressure was severely elevated from the pain. His doctor was concerned he might be suffering from an aneurysm.

Back at the hospital, there was good news and bad news. The good news was that he didn’t have an aneurysm. But the bad news was that he did have a six centimeter mass extending from his T5 vertebrae.

Sid was diagnosed with osteosarcoma, a form of bone cancer that is rare for an otherwise healthy 45 year old to have. The first order of business was to get the cancer out. A surgeon successfully removed the cancerous vertebrae and fused his spine with a titanium frame.

With the tumor removed, Sid underwent an aggressive version of the standard of care for his cancer type. He did stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT), several rounds of intensive chemotherapy, and added proton beam therapy.

The impact was brutal. The chemotherapy was so intense that he needed four separate blood transfusions. Like all chemo patients, he lost his hair. For weeks, he could barely get out of bed to go to the toilet. “It destroyed me,” Sid told me.

And these were just the temporary effects. His heart is less flexible now and he is anemic. Sid says that he is “stupider now,” referring to the toxic impact of systemic chemotherapy on his brain. (I’d note that his intellect is still clearly far out of distribution relative to most people.)

In his first round of treatment, Sid deviated only once from more traditional care. José M. Mejía Oneto had founded an oncology startup called Shasqi and gone through the same YC batch as Sid in 2015. Well before he was ever a patient himself, Sid had befriended José and invested in his company.

In 2020, Shasqi became the first YC company to start a clinical trial. They were testing new chemical strategies to make chemotherapy more targeted. But the trial wasn’t designed for Sid’s cancer type. As Sid struggled through systemic chemotherapy, he worked with Shasqi to file an investigational new drug (IND) application with the FDA for a trial where he would be the only patient. The application was approved and he was able to use the technology.

For two years, regular checkups confirmed that Sid’s cancer remained in remission. But during a checkup in 2024, imaging showed evidence of local recurrence. The cancer was back.

Sid had reached the end of the road for the standard of care. He’d had surgery. Radiation. The most aggressive chemotherapy possible. And the cancer was back.

To Sid’s surprise, his medical team didn’t have much else to say. It wasn’t unusual for a cancer to outsmart therapy and recur. It was the norm. But in Sid’s programmer brain, this didn’t compute. He wanted to live.

Because the diagnosis with osteosarcoma at his age is rare, he didn’t meet the inclusion criteria for any clinical trials. It dawned on Sid that without taking extreme measures, he would die. “It became my own job to keep myself alive. Nobody else was going to do it for me at this point,” he said.

At the end of 2024, Sid transitioned from CEO to Executive Chair of GitLab, saying, “I want more time to focus on my cancer treatment and health.” He was beginning to reorient his life to be able to go “all out” to cure his cancer.

Just a few months earlier, Paul Graham had written an influential essay about what makes founder-led companies so special. Entitled Founder Mode, Graham reflected on the fact that great founders often embed themselves more deeply in the details than hired professional managers. He wrote, “Whatever founder mode consists of, it's pretty clear that it's going to break the principle that the CEO should engage with the company only via his or her direct reports.” Many crucial decisions lurk below that level of abstraction.

Sid was leading GitLab in founder mode and his cancer care in manager mode. It was time to flip that before it was too late.

Chapter Two: “I’ll Talk to Anyone, I’ll Go Anywhere, and I Can Be There Anytime”

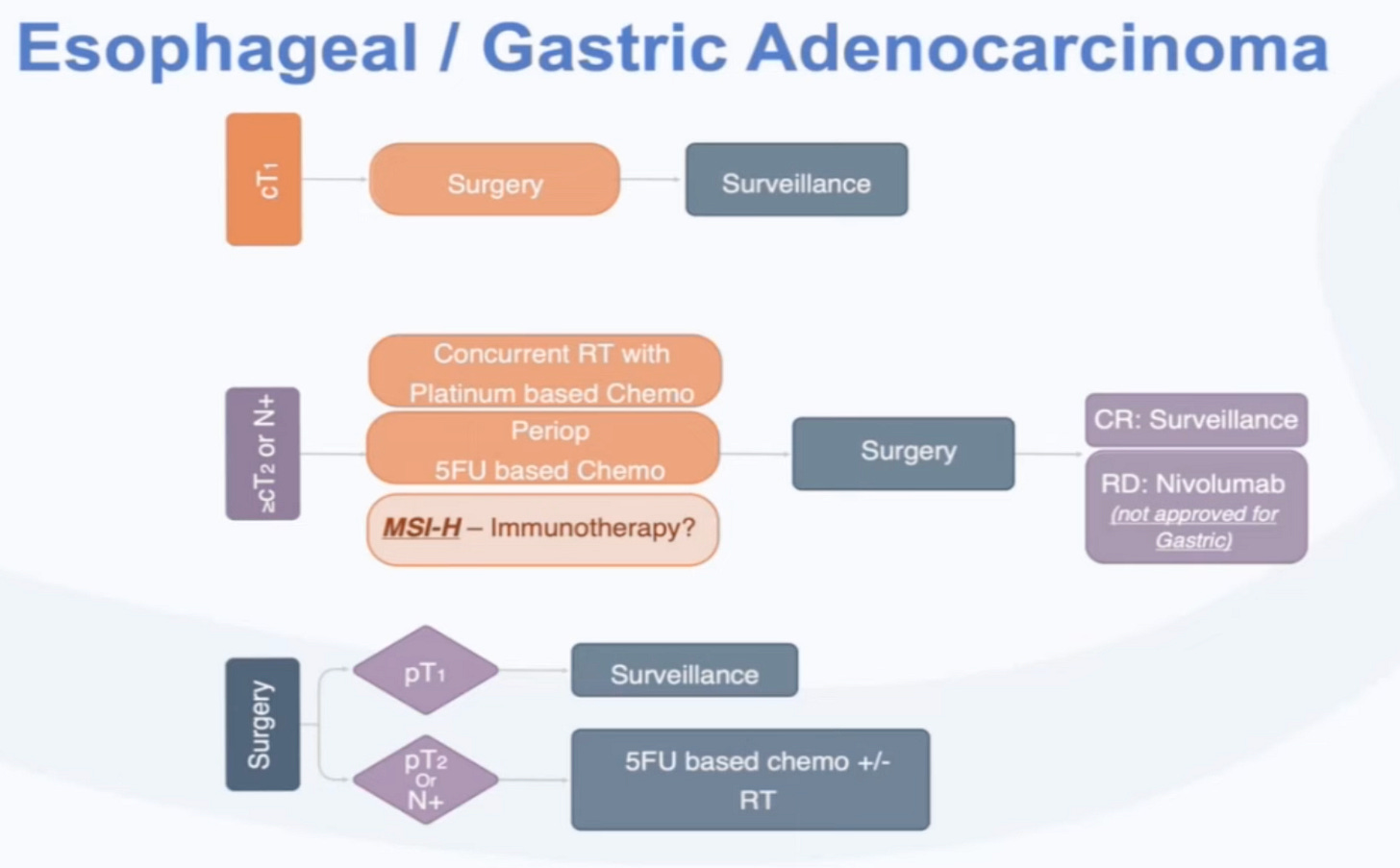

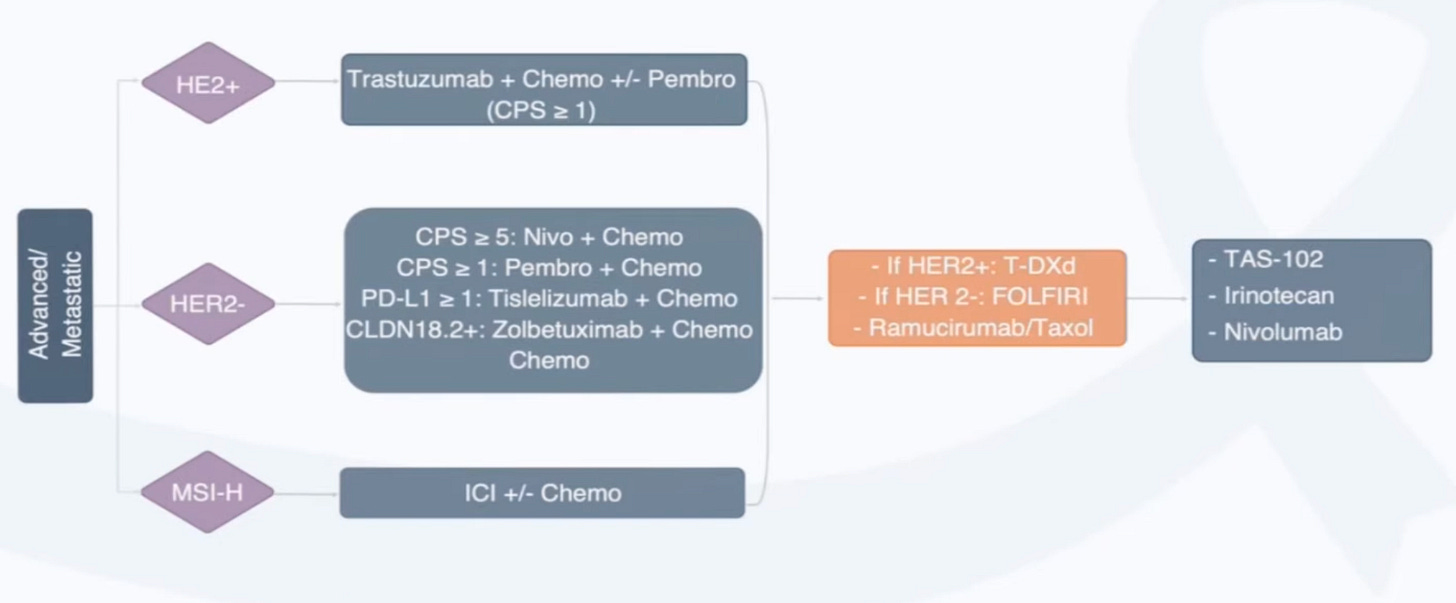

Programmers and oncologists have overlapping terminology. The decision trees for treatment regimens based on a patient’s biomarkers are referred to as algorithms.

These algorithms are often depicted in flowcharts. Here’s an example of what the current standard of care looks like in esophageal and gastric cancer.

Based on clinical staging (e.g. cT1, cT2) determined by doctors using scans or other diagnostics and pathologic staging (e.g. pT1, pT2) determined by pathologists using tissues, different combinations of treatment are applied. If a cancer progresses or metastasizes, more sophisticated biomarkers can guide more sophisticated therapies.

Sid had exhausted the treatment algorithm for his osteosarcoma. Thinking about the problem from first principles, he knew that he needed more advanced diagnostics to make decisions about what to do next. And he needed to find or develop new therapies to take based on that information.

He established some principles for his next phase of care:

Maximal Diagnostics. The goal is simple: do every diagnostic available as often as possible. Just like GitLab’s operating culture, no unit of information is too small to document.

Make 10+ Personalized Treatments. Since no more treatments were available, Sid scaled up his engagement with companies and academic researchers to tailor new drugs based on what he learned about his cancer.

Treatments in Parallel, Not Serial. Typically, a single therapy is used until it’s clear there is a need to change course. Instead, Sid aims to iterate faster, testing multiple therapeutic hypotheses in quick succession and empirically measuring the response with diagnostics, “rather than waiting for my cancer to progress.”

Each principle radically differs from how oncologists typically approach care. So he began to assemble a team willing to embark on this experiment with him. The first pillar of his new team included private concierge care practices and services—such as Private Medical, Private Health Management and Pathfinder Oncology—that could help him scale up and manage his diagnostic regimen.

Sid’s new suite of diagnostics can be divided into five primary categories.

Every cutting-edge genomic tool is deployed.

He uses single-cell sequencing instruments developed by 10x Genomics to measure cell-type specific expression of genes that could potentially be targeted by treatments. This technology also resolves the exact T-cell receptors (TCRs) of the T cells that have infiltrated his tumor, potentially enabling highly targeted immunotherapies.

This is paired with “bulk” DNA and RNA sequencing where his cancer cells are measured in aggregate to assess the broader mutational landscape of his tumor.

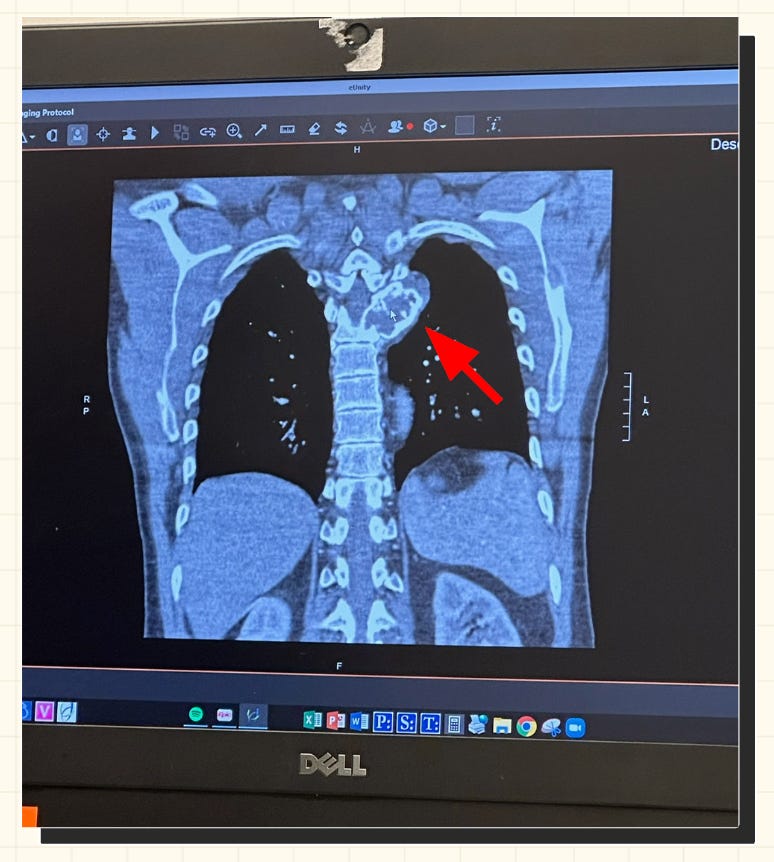

But that’s not where sequencing stops. He routinely uses minimal residual disease (MRD) tests from multiple providers, which scan for trace amounts of tumor DNA that can end up circulating in the blood. These tests have varying sensitivity and specificity but can be used as an early signal for disease recurrence, especially if multiple tests are positive multiple times.

Another more experimental tool in the toolbox is the use of assays for modeling the potential response to a drug in the lab. Sid has initiated collaborations with various academic labs developing different organoid systems for this purpose. He has even embarked on making organoids using his own cancer cells.

The last major pillar is the use of pathology stains to confirm the most promising genomic hypotheses in tissue samples from his tumor. Blood samples are much easier to collect than tissue samples, which are a more finite resource. So this step is done less frequently and with more consideration.

As Sid began blazing this trail, he reconnected with Jacob Stern. The two had been connected by José at Shasqi earlier, but they now shared an obsession: single-cell sequencing. Sid was a personal power user of 10x Genomics and Jacob was a director at the business.

When Jacob heard about how Sid was using their single-cell technology, he invited him to visit 10x and speak about it. As Jacob helped prep the talk, Sid showed him his health notes. Jacob was blown away. “I realized that this guy was living thirty years in the future,” Jacob said. It was the most exciting application of 10x technology he’d ever seen. Sid was making the mission of “mastering biology to advance human health” a reality for himself.

Sid recruited Jacob to join him full-time, effectively becoming the CEO of his care. Jacob now sequences and orchestrates the complex symphony of Sid’s diagnostic and therapeutic regimen. He liaises with hospitals and physicians. Meetings with researchers and startup founders pack the remainder of his calendar. No stone is left unturned in pursuit of nuggets of information that could lead to a new treatment.

Throughout 2025, Sid and Jacob have moved extraordinarily fast. With the support of the broader team, which consists of concierge medical services, a clinical advisory board, and a scientific advisory board, Sid’s armamentarium of treatment options has expanded from zero to dozens.

With all of this activity, it can be challenging to get a sense for what decisions actually look like in practice. But zooming in, one diagnostic discovery helped credential a therapeutic decision that made a particularly outsized impact.

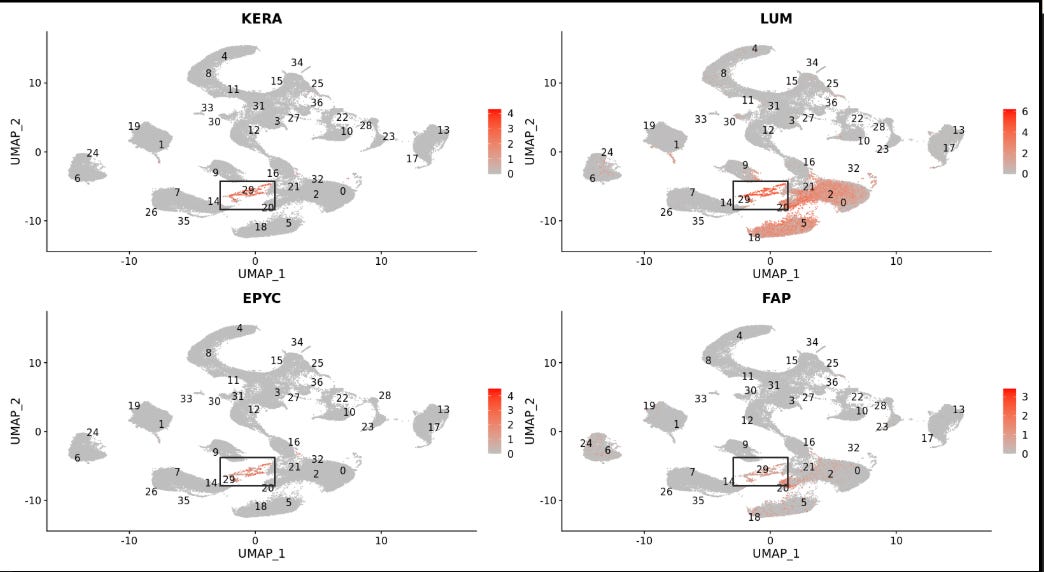

When expert computational biologists analyzed Sid’s single-cell data, they made an important observation: many of the genes with the greatest differential expression relative to healthy cells were canonical markers of fibroblasts.

Fibroblast cells are widely distributed throughout healthy tissues and play a critical role in wound healing. But tumors can warp the wound healing pathway to gain mass and scaffold a protective matrix within the tumor microenvironment, acting like a wound that never heals. Sid’s cancer appeared to have learned this trick.

In parallel, one of the concierge medical services had surfaced an experimental therapy in Germany that directly targets FAP, one of the fibroblast-related genes that was shown to be up-regulated. Soon, Sid was en route to Germany. As Sid says, “I’ll talk to anyone, I’ll go anywhere, and I can be there anytime.”

The experimental treatment being developed in Germany was a radioligand therapy. These medicines consist of two parts. The first is a targeting compound called a ligand. Attached to the ligand is a radioisotope, which is an unstable atom that undergoes decay, emitting radiation. The goal is for the ligand to precisely deliver this infinitesimally small nuclear bomb to cancer cells, triggering their death.

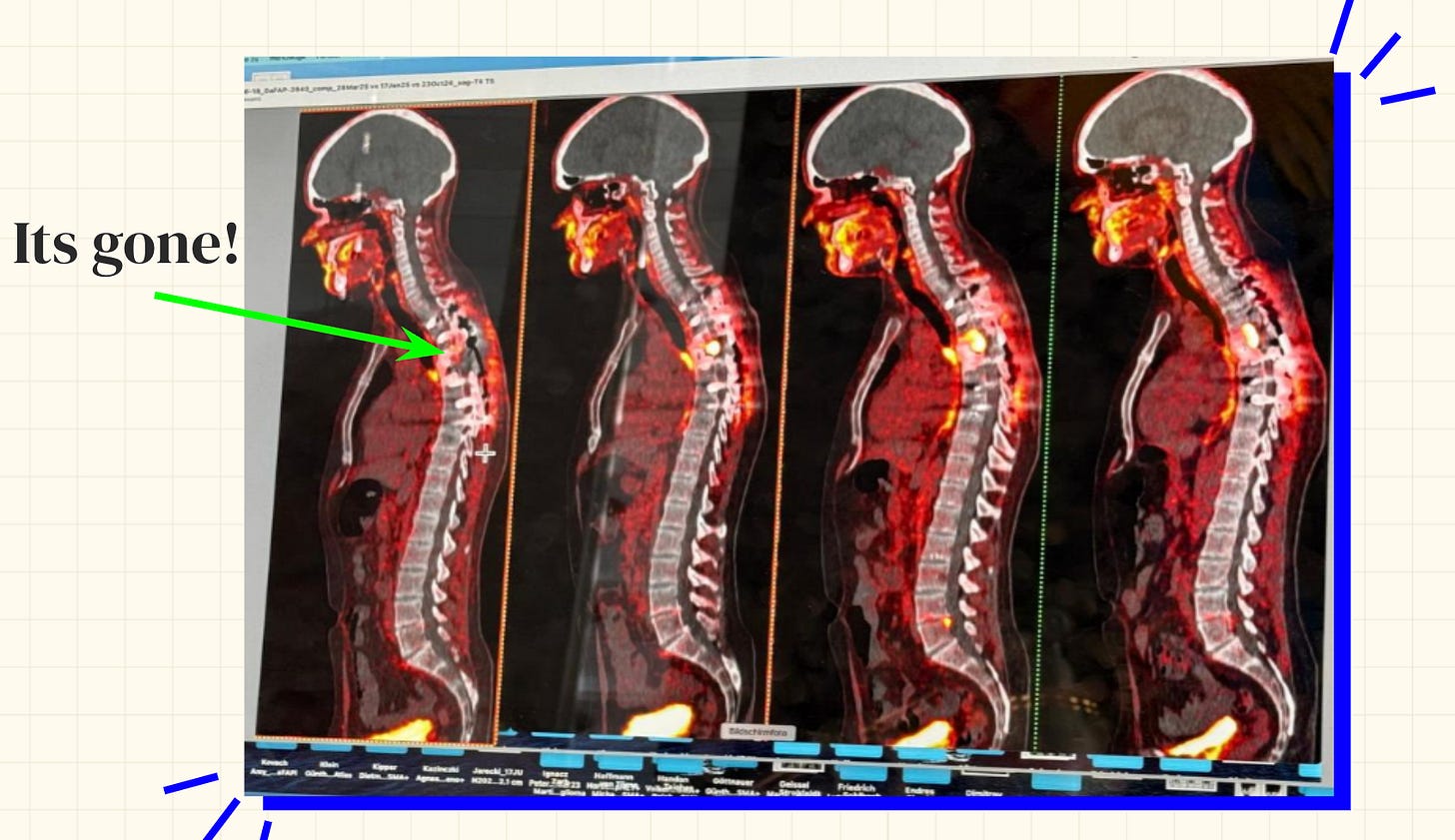

A critical feature of radiotherapy is that the targeting ligand can be used as both a diagnostic and therapeutic tool—which is why it is sometimes called a theranostic. First, the ligand can shepherd a “cold” isotope that can be used for imaging. Sid’s tumor lit up. In conjunction with the single-cell analysis, the localized imaging response gave Sid confidence to move forward with the therapy.

Next came the “hot” payload. In Sid’s case, this was Lutetium-177 (Lu-177), the same warhead used in Pluvicto, one of the first breakthrough radiotherapies. Sid was dosed with the medicine and then quarantined for two days. He was given a small handheld monitor to track his radioactivity levels. For two weeks after the treatment, his urine was also carefully collected and discarded as his body flushed out the isotopes.

While radiotherapy can sound extreme, Sid found it dramatically more tolerable than chemotherapy. The experiences were as different as night and day. Rather than spreading throughout his entire body and wreaking havoc, the radiotherapy primarily concentrated at the site of his tumor. After getting out of quarantine, Sid got busy planning a wine tasting to celebrate.

And in the coming months, there would in fact be a lot to celebrate. The radiotherapy worked. Sid’s cancer shrank enough to become surgically operable again.

With fresh tissue from the surgery, they reanalyzed the immune cells within the tumor. It was a chance to empirically measure the response to the immunotherapy drugs that Sid had been taking in parallel.

The results were striking.

One measurement is what percentage of infiltrating cells are T cells. These cells are critical members of the adaptive immune system, which can learn to recognize persistent threats and establish immune memory. Most immunotherapies—including the checkpoint inhibitor that Sid had taken—work by boosting the anti-cancer T cell response.

When Sid’s cancer had returned, only 19% of the infiltrating immune cells measured by single-cell sequencing were T cells. After the surgery following radiotherapy, 89% of the cells measured were T cells. It seemed that the checkpoint inhibitor, a neoantigen peptide vaccine, an oncolytic virus, and the radiotherapy itself, had set Sid’s anti-cancer immune response into hyperdrive.

Now Sid and his care team are playing a different game. Like Magic Johnson’s HIV, Sid’s cancer is no longer detectable. But with a motto of “Stay Paranoid,” they are continuing to build out infrastructure even with negative test results.

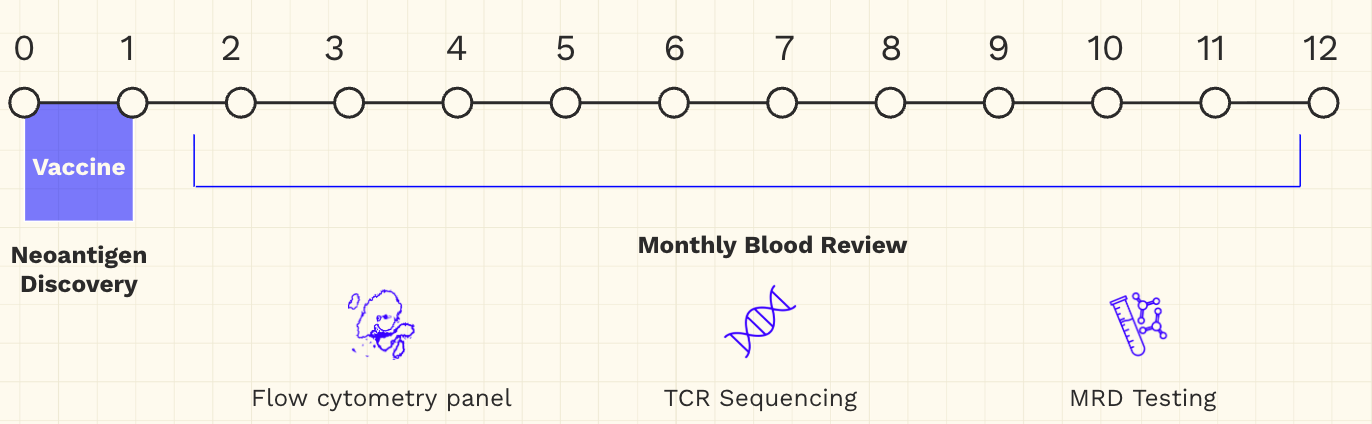

Sid’s next course of treatment is an mRNA-based personalized neoantigen vaccine with the goal of sustaining the immune response they have already elicited. Of course, this treatment will be coupled with an in-depth monthly blood review to assess its impact.

As a backup to the backup plan, they are also developing personalized cell-based therapies in collaboration with leading academic groups. Based on more diagnostic data, the plan is to equip these cells with cutting-edge genetic logic gates that trigger cell killing in response to multiple signals rather than just one—another example of oncology and computer science blending together. But the goal is to never need these “nuclear options” if they can prevent recurrence with the less aggressive tools in their arsenal.

All of this is nothing short of remarkable. “Sid’s is a unique case,” Jacob said. Few people in the world have the resources or sophistication to pull even a fraction of this off. Sid has also made it clear that he would rather die from treatment than disease, which is an aggressive and personal stance.

But extreme cases like this often carry a residue from the future—especially where technology is concerned. Consider the computer revolution. The first computers filled entire rooms. They were only accessible to a select clergy of experts capable of operating them. Now we all carry more computational power in our pockets than NASA engineers had access to when landing men on the moon.

Sid’s case reveals the power of frontier cancer therapies. Is it possible that the average cancer journey of the future comes to look more like Sid’s? If so, what are the current bottlenecks that could hinder that transition?

Chapter Three: “I’m the Kool-Aid Man Breaking Through the Wall”

Sid and Jacob are both technologists. They can’t help but think of the ways that lessons from Sid’s journey could be scaled. It’s in their very nature.

When I first met Jacob, we went for a walk. As we wandered along The Embarcadero, spanning San Francisco’s eastern waterfront, we talked about Sid’s case. I asked him how much of this he thought could be repeated. He told me a story.

Before Jacob joined 10x, he’d spent time at Palantir earlier in his career. Although Palantir’s market capitalization is approaching $500B, few people have a great sense for what the company actually does. In her article, What Does Palantir Actually Do?, Caroline Haskins argued that this may be because “unlike consumer-facing startups that need to clearly explain their products to everyday users, Palantir’s main audience is sprawling government agencies and Fortune 500 companies.”

Palantir builds software infrastructure for these incredibly complex organizations. A big part of doing this is figuring out what these organizations need. Once a solution is engineered, it needs to be installed. To help make both steps easier, Palantir pioneered a role called the Forward Deployed Software Engineer (FDSE) that embeds within an organization.

FDSEs learn the shape of the problem and bolt on the first solution as quickly as possible. Over time, the solution can be refined, automated, and scaled. Many of Palantir’s features originate from lessons learned in “deployment.” Jacob told me about this philosophy. First, learn the problem. Next, solve it. Finally, harden the solution and scale it.

Similarly, Sid and Jacob and the broader team have accumulated immense firsthand experience navigating the Leviathan that is the American healthcare system. They now have a map of the territory. In order to solve problems for Sid, they’ve had to craft many rough solutions. In the future, these solutions could be scaled.

To understand how to scale a radically different approach to oncology, it’s worth examining the problems they faced when the rubber met the road.

First off, oncologists and the hospitals that employ them are not accustomed to patients going founder mode. They are used to manager mode, where patients delegate responsibility and autonomy to physicians. Oncologists determine what tests are ordered and what treatment is administered. Deviating from the standard path is met with resistance.

Consider diagnostics. Sid’s “maximal diagnostics” strategy is unusual. Achieving this ethos has required two big differences from standard clinical practice.

First, some of the more involved assays require cryopreserved tissue samples. Typically, hospitals only collect formalin-fixed paraffin embedded (FFPE) samples, which are helpful for conventional pathology reports, but destroy most of the nucleic acid information within the tissue. Second, Sid wants access to these tissue samples in order to generate data and store it.

Sid and his team were astonished by the difficulty of achieving both tasks.

Pathology departments prefer to run standard protocols. Cryopreservation is not standard. Accommodating this introduced novelty and risk. What if they made a mistake? Would they be liable?

And hospitals are very familiar with collecting samples and running tests. They are much less accustomed to collecting tissue samples and handing them off to patients. In many cases, there are simply no procedures to do this. Again, what is the liability associated with doing this?

Sid described the “incredible struggle at every hospital” to get access to his own tissue. Doing so has required “forward deployed tissue extractors,” who navigate hospital bureaucracy and don’t take no for an answer until they get sign-off and transfer. It is still a major struggle to access and move around historical samples.

Gathering genomic data has been another challenge. After the completion of the Human Genome Project in 2003, genomic technologies underwent a cost reduction more extreme than Moore’s Law. What cost billions of dollars can now be accomplished for less than $1,000. Still, whole-genome sequencing hasn’t become a fixture in the standard of care in oncology, a disease of the genome.

Jacob describes it as “shockingly hard” to obtain sequencing data beyond standard reports. For research labs, companies like Plasmidsaurus offer overnight plasmid sequencing. But using this type of service in a clinical setting requires jumping through hoops and cutting red tape.1

Part of this is arguably for good reason. There is a real fear that our sequencing capabilities have outstripped our ability to make sense of the resulting information. Even if we could, it’s unclear that there will be actionable treatment decisions available. It’s more pragmatic to stay under the lamp post where we can see—and to use the most well understood treatments.

But imagine trying to land this argument with Sid, the information maximalist. He obviously wants the information. And just like the GitLab Handbook, he expects that if there isn’t an answer already, they can figure it out and write their own.

When considering this problem, a natural set of questions emerges. Why is the Oncology Handbook so sparsely populated? Shouldn’t the genomics revolution have resulted in a Cambrian explosion of new treatment options? Why has measurement outstripped treatment to such a large degree? As Ruxandra Teslo asked, Why haven’t biologists cured cancer?

Part of the answer is that cancer is an extraordinarily complicated disease. Cancers are not static targets. They can evolve to evade even the most promising therapies.

But after his care experience, Sid has joined the growing group of people asking hard questions about the efficiency—or lack thereof—of biopharma innovation. As I frequently cite, in 2012, Jack Scannell and his colleagues observed that “the number of new drugs approved per billion US dollars spent on R&D has halved roughly every 9 years since 1950, falling around 80-fold in inflation-adjusted terms.”

This phenomenon, now widely known as “Eroom’s Law,” leads to an upside down picture where the exponential biotech revolution coincides with an exponential decline in the efficiency of pharmaceutical innovation.

Scannell and many others have attempted to outline the causes.

Much like literature, drugmakers need to compete against the entire canon of work that has come before them. And they do so in a much less favorable regulatory environment. The Eroom’s Law authors wrote, “Each real or perceived sin by the industry, or genuine drug misfortune, leads to a tightening of the regulatory ratchet, and the ratchet is rarely loosened, even if it seems as though this could be achieved without causing significant risk to drug safety.”

But let’s set aside discussion of the causes for now. The fact of the matter is that it’s become exorbitantly expensive to develop new drugs—especially for oncology. A recent analysis estimated that between 2017 and 2020, the average cost to develop a new oncology medicine was $4.4 billion.

This warps the incentives of drugmakers. One needs to see a path to astronomical peak yearly sales—on the order of billions of dollars—to justify this type of R&D expenditure. Anything less than a blockbuster hit doesn’t move the needle.

What this means in practice is that it’s become “so expensive to generate evidence that we don’t generate evidence for very much,” as Sid puts it. Several times now, Sid’s team has discovered promising experimental medicines that they’ve had to rescue from companies on the verge of bankruptcy. Drugs that may mean the difference between life and death for one patient can be discarded because of underwhelming financial estimates of their broader market potential.

And it’s hard to argue with this logic. In a paradigm of scarcity, we should be using our resources to advance the assets with the greatest chance to help as many people as possible. But there might be another way.

What if we could scale the development of medicines tailored specifically for a given patient?

There are two broad buckets to consider for this paradigm.

The first is drug repurposing. Sid has had a lot of success with this approach already. Guided by maximal diagnostics, Sid’s team has identified several drugs under development for other cancer indications that seemed likely to also improve his disease. And there are surprisingly flexible regulatory pathways already in place to accommodate this.

So far, using the Individual Patient Expanded Access - Investigational New Drug Application (IND), known as Form 3926, Sid has gained access to five experimental medicines where no trial would have otherwise been available to him. In each case, the FDA has accepted his application within 48 hours. “The FDA wants me to live,” Sid says.2

Surprisingly, hospital institutional review boards (IRBs) have been more challenging to navigate than the FDA. Sid describes it as a “vetocracy” where one member of the board can block treatment based on even the smallest concern. Large hospital systems, which are concerned with adhering to procedures and avoiding liability, have strong organizational antibodies to mitigate any threat of risk. Still, Sid has found drug repurposing to be a powerful tool in his arsenal.

Beyond repurposing, there is the vision of designing a drug from scratch based on a molecular understanding of one’s disease. This is typically referred to as personalized medicine. So far, Sid has initiated the development of multiple new experimental medicines in collaboration with academic research groups and startup companies.

But there are other examples where it’s possible to see a path to more scalable personalized medicine. One example is the personalized use of CRISPR for genetic disease. In June of 2024, I wrote about the vision, passionately spearheaded by Fyodor Urnov, to use CRISPR’s inherent programmability to design custom therapies for individual patients. In parallel to the scientific and clinical advances, the FDA proposed a new regulatory framework to more flexibly accommodate this type of programmable platform technology.

In May of 2025, this all came together in spectacular fashion. A baby boy in Philadelphia suffering from a rare metabolic disease was dosed with the first ever personalized CRISPR therapy.3 Baby KJ, as he is called, went viral. His story was picked up by every major news outlet. In response, leaders at the FDA proposed a new “plausible mechanism pathway” to enable more treatments like what KJ received.

Oncology is undergoing a similar renaissance. CAR-T therapy, which is one of the biggest breakthroughs in cancer care in decades, is not a drug with a universally defined chemical structure or biological sequence. Instead, it is a process for genetically engineering a patient’s own immune cells to become sentinels on the hunt for cancer. This also required regulatory flexibility.

Similarly, the type of personalized neoantigen vaccine that Sid is going to take is another striking example of a custom tailored molecular medicine. Let’s consider the workflow of this therapy, which I’ve written about before.

A patient’s cancer is sequenced. This data is piped into a bioinformatics pipeline with complex machine learning algorithms that predict which antigens should be used in the vaccine. These designs are then physically instantiated in personalized lots and packed into lipid nanoparticles—much like the type of medicine that baby KJ received.

In December of 2023, Moderna published incredible clinical results showing that their version of this process, in combination with a checkpoint inhibitor, cut the risk of cancer recurrence or death nearly in half for melanoma patients.

While these results are remarkable, there is still enormous room for improvement. Much like early computers, these therapies are still too expensive and slow for broader adoption. And they still aren’t delivering the types of complete responses that CAR-T therapies have now repeatedly achieved.

Decade, a company we partnered with at Amplify, is on the case. While they are still in stealth, the long-term vision set forth by the founders, Devin Scannell and Brian Naughton, is to enable “programmable radiotherapy.” The idea is to use many of the tools pioneered by the vaccine developers to make custom radiotherapies like what Sid received in Germany much more commonplace. If they succeed and the process is as potent as we hope, it’s the type of treatment I’d want for any member of my family.

Zooming out, all of these new personalized platform technologies represent a major shift. Remember: a real concern with collecting rich genomic data for a cancer patient is that we won’t be able to do anything with it. Now, there are approaches being developed to close the loop. Platform technologies are being developed to ingest exactly this type of information and to spit out custom drugs.

One of Sid’s biggest problems is that he is grasping at a future that hasn’t quite come into fruition yet. Or as he likes to say, “I’m the Kool-Aid Man breaking through the wall.”

Analyzing his data has required hiring computational biologists with graduate degrees. Repurposing medicines has required interactions with the FDA and hospital IRBs. Developing a personalized therapy has required sweating every little detail about the manufacturing process. He couldn’t have done any of this without his resources and team.

But let’s imagine what this could look like, in ten or twenty years, at scale.

An individual spots an abnormality on a consumer cancer diagnostic test, from one of many providers such as Prenuvo or Function Health.4 They decide to sign up for a consumer concierge oncology platform, which charges $1,499 for an initial workup.

Once they are onboarded and tissues are transferred to their personal biobank, the oncology service fires up some AI agents. After processing the individual’s entire medical history, the diagnostic agent orders a few more tests. Once returned, the results are passed off to the bioinformatics agent who generates a PhD’s worth of analysis in a matter of hours before distilling down the core details into a succinct five page report.

At this point, it’s clear the individual has a small cancer in their pancreas. But it’s early enough that surgery isn’t required. Based on the specifics of their tumor microenvironment and the exact antigens that are present, the drug hunter agent selects a checkpoint inhibitor (now generic, it costs less than $1,000) and an off-the-shelf cancer vaccine to rev up the immune system. Supercharged T cells hunt down any rogue cancer cells straying from the pancreas and kill them.

No chemotherapy is ever used. A custom radiotherapy is used to obliterate the physical tumor. Of course, imaging is used to confirm safety and tumor targeting before the cancer-killing warhead is ever delivered.

The total bill from start to cure is $175,000. Part of this is covered by the pool of money for discretionary health spending in their CHOICE account. The remainder is picked up by their health insurance provider—who is happy to save a considerable amount relative to the prior average cost of treating a pancreatic cancer patient, which was ~$250,000. Everybody wins.

Let’s be clear about a few things.

First off, despite starting my career as a cancer researcher, I am not a trained oncologist. And neither is Sid. Therefore, none of this should be construed as medical advice.

For example, Sid’s choice to test multiple drugs at lower doses in parallel is a personal one. While he felt it greatly reduced the side effects of any one drug, this is not how oncologists currently deliver care. The same can be said for all of his diagnostic testing.

This is also not an elaborate conspiracy about doctors or pharmaceutical companies hiding a secret cure for cancer behind closed doors. Reality is far more nuanced than that.

This is a case study. Just like business school professors devoted themselves to studying the operational practices that Sid established at GitLab, we should study the personalized protocols that he implemented during his extraordinary care journey.

Sid’s story has left me with a visceral feeling of William Gibson’s quote that we considered earlier: “The future is here, it’s just not evenly distributed.”

Widely considered the father of the cyberpunk genre, Gibson is one of the most prolific and influential living science fiction authors. His body of work sometimes reads like a detailed examination of this one central idea. Gibson’s cyberpunk cities are disorienting landscapes where people use cutting-edge virtual reality headsets while living in decrepit project apartments. Even sci-fi space habitats contain rooms filled with ancient relics.

The future always crawls clumsily out of the past.

This is what American healthcare feels like. I get my own medical care through a large health maintenance organization (HMO) in the Bay Area. Bugs in the janky Web portal frequently make it impossible to book an appointment or access my records.

But when I am seen, the care is often remarkable. My wife and I are expecting our first child, who we’ve already seen in stunning detail with futuristic imaging technology that has become totally routine. The experience was especially surreal because the machines were operated in tiny rooms full of charts and furniture that look like they haven’t changed since the time my mother would have been visiting for her own prenatal appointments.

Sid’s story is the most extreme example of this. He is living in the future. Many of the technologies used in his care represent the frontier of medical science. But navigating our existing labyrinth of a system to gain access to them has required herculean effort and persistence.

And that’s where things are. Oncologists want to cure their patients. Researchers and companies are making big strides in inventing the tools to help them do that. And regulators want to implement guidelines and pathways that keep pace with innovation.

The challenge is to line up all of these vectors of progress in order to achieve large-scale structural change. It can feel like every biomedical breakthrough is absorbed by a black hole that renders it invisible to any metric of progress. We’ve come to accept measurements of clinical progress in oncology on the scale of months, rather than years—let alone lifetimes.

Maybe the biggest lesson from Sid’s story is to be hopeful that the future is actually closer than it can sometimes feel. Things have a surprising way of happening gradually and then suddenly.

Thanks for reading this essay about Sid’s care journey. This wouldn’t have been possible to write without Sid’s “radical transparency” about his experiences. I’ve learned a lot from both Sid and Jacob, so I hope this essay proves to be of value for you, too. If you want to learn more, it’s worth checking out a website, sytse.com/cancer, that Sid and his team have put together. There are more incredible scientific vignettes and data resources than I was able to cover here.

If you don’t want to miss upcoming essays, you should consider subscribing for free to have them delivered to your inbox:

Until next time! 🧬

Eric Topol previously wrote an interesting article about this disconnect entitled Human genomics vs Clinical genomics.

Adjacent to Form 3926 is the broader set of right-to-try-laws moving their way through the legislative process. The core concept is that terminally ill patients should be able to test new experimental therapies that are already in at least Phase 1 trials. My understanding is that this would lower the barrier, such that each patient wouldn’t require a Form 3926 when making this type of choice.

I’ll admit to being somewhat pleased to have correctly predicted two of the three manufacturers that would be used in my earlier piece. IDT was used for nucleic acid synthesis and Aldevron formulated the final drug. Although I didn’t predict that the lipid nanoparticle would come from Acuitas Therapeutics.

It’s been fascinating following the discourse about a malpractice lawsuit levied against Prenuvo when they didn’t detect warning signs of one user’s stroke in advance. One physician said that the report in question “reads like AI generated slop with barely any details that I would see in an actual radiologist report.” Max Hodak, on the other hand, wrote, “I personally know of at least 4 cases where Biograph unambiguously saved the life of someone in their 30s-40s who went in thinking they were totally healthy. (MRI by far most important signal) This pushback on advanced preventive medicine is deeply misguided.” This entire concept is clearly in a weird spot in terms of both technological readiness and cultural acceptance. Interestingly, reanalysis of Sid’s own off-the-shelf MRD results have also revealed critical errors in some of the reports.

This is your best work yet, Elliot. What an incredible story, and no one could have told it better. Perfect mix of profile, science, and glimpse into a better future. Bravo man!

Do you know how to get in touch with Sid? I’m a biologist, my mom is also a biologist. My mom was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer late 2024. We also went into founder mode, conceived a novel method to improve the efficacy of chemo for many cancers, and my mom’s use of this method has coincided with an extreme response.

Power in numbers - maybe we can connect a GitLab for cancer?