Drug discovery origin stories

pharma origin stories, modern equivalents

Welcome to The Century of Biology! Each week, I post a highlight of a cutting-edge bioRxiv preprint, an essay about biotech, or an analysis of an exciting new startup. You can subscribe for free to have the next post delivered to your inbox:

Enjoy! 🧬

Overview

Microscopes are a universal symbol of biological research. They offer a deeply general and essential capability—the power to look inside the world of cells and tissues. For hundreds of years, they have been one of the most essential tools for studying living systems. Now, modern DNA sequencing offers us the ability to measure the instruction set present in every cell. It is becoming the “broadly enabling microscope” of the 21st century.

Over the last two decades, DNA sequencing has decreased in cost faster than any other technology, ever. Illumina has been the most dominant force in the market during this revolution. The company has been content to serve as an infrastructure layer, offering sequencing as a tool to companies and researchers using it to develop products and medicines. Until they weren’t.

Illumina made headlines earlier this month when they announced a new partnership with Deerfield Management to pursue their own drug discovery program. Based on the substantially higher success rate of drug targets with genetic evidence, Illumina is aiming to use their AI and genomics expertise to “drive a step-change in the pace and efficiency of therapeutic development.”

This decision was met with a mixture of surprise, excitement, and also skepticism. Illumina is not the first to attempt the transition from infrastructure to discovery—tool builders can be lured by the massive potential upside of a successful drug program. This led Sri Kosuri to ask: “Every tools company eventually becomes a discovery company in bio. Is there an example of a company that’s made that transition well?”

There is an interesting historical framing that flips this question on its head. As the inimitable Brandon White points out, the “supermajority of the 100+ year old drug discovery companies of today built their initial business momentum elsewhere.” In other words, a valid counter-question is: which of the major pharma companies today actually started as drug discovery companies?

In order to explore this idea, I’m going to talk about some of the historical pharma origin stories, and and examine what some of the modern equivalents may be.

Pharma origin stories

Some of the largest pharmaceutical companies are really old. Many have even been around longer than the Food and Drug Administration. These massive global corporations all had more humble origins well before the high-risk, high-reward paradigm of modern drug discovery.

Before ever being involved in pharmaceuticals, Johnson & Johnson spent the better part of a century selling a wide variety of consumer products. As antiseptic surgery become more widely adopted towards the end of the 19th century, J&J built a profitable business selling sterile surgical supplies and medical guides. They continued to develop useful but thoroughly unsexy products such as Band-Aids and Baby Soap.

It wasn’t until J&J had existed profitably for nearly 100 years that they moved into drug development with the acquisition of McNeil laboratories and sale of Tylenol in 1959, and the following acquisition of Janssen Pharmaceuticals in 1961. Due to their position as a stable and massive corporation with a higher credit rating than the U.S. government, they have been able to underwrite the risk of modern drug discovery and benefit from the upside.

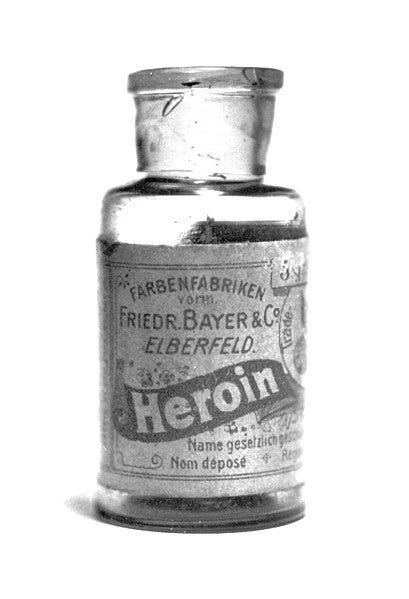

As Nikita Singareddy (who writes the excellent Waiting Room newsletter) has pointed out, many pharma companies originally developed their chemical synthesis capacity selling dyes. Bayer followed this trajectory, starting in 1863 as a dyestuffs factory before developing and manufacturing Aspirin. They also had a successful stint as a heroin supplier—putting the drug in drug discovery.

There are many other examples of both dyes and drugs generating profits for pharma companies, with Novartis’s origins tracing to the merger of a silk-dyeing factory and a dyewood mill in Basel, or Merck getting its start as a German drug store and manufacturer selling morphine and cocaine.

It wasn’t until the 20th century that the FDA came on to the scene. In 1906, Teddy Roosevelt passed the Pure Food and Drug Act in an attempt to cut down on mislabeled foods and drugs being shipped between states. Half a century passed where the FDA continued to gradually accumulate regulatory power.

Then, in 1962 there was a massive inflection point. After a major tragedy where thousands of children were born with birth defects due to their mothers being prescribed thalidomide, the Kefauver–Harris Amendment was signed in to law. This legislation introduced the requirement for pharmaceutical companies to prove the efficacy and safety of a new drug before having it approved.

This shift marked the beginning of the modern drug discovery paradigm. It substantially increased the time, cost, and difficulty associated with bringing a new drug to market. Because of this, additional legislation was ultimately passed in 1984 that granted patent exclusivity to approved drugs in order to incentivize development.

As the legislation and difficulty associated with drug development increased, it made it difficult for anybody but the “megacorps”—to use William Gibson’s sci-fi terminology—to make new drugs. Even biotech companies today that start out as discovery companies either sell to or partner with existing pharma companies.

Modern equivalents

Many of the massive incumbent pharmaceutical companies were profitable businesses well before the establishment of the modern drug discovery process. What lessons can we learn from this? What types of companies being built today could make this transition?

Illumina is certainly going to make an attempt. Similar to how Bayer leveraged it’s chemical synthesis capacity from dye making, Illumina does have technical infrastructure for large-scale genomics efforts and accompanying bioinformatics. As their patents come to an end, strategies like their intension to acquire GRAIL and to move into drug discovery offer the promise of capturing more vertical value relative to being a horizontal technology provider.

Whether or not Illumina successfully navigates this transition, there are several different types of biotech businesses that will likely try something similar. 23andMe has attempted to build on their business model of providing consumer genetics kits by moving into drug discovery. Schrödinger launched a collaboration with Nimbus Therapeutics to develop drugs in addition to their primary offering of selling drug discovery software.

There are likely a variety of additional options that we are all currently failing to imagine. Profit from selling tools, software, consumer products, or other services all could potentially be used to launch the next generation of massive tech-enabled pharmaceutical companies. As Brandon White argues, the combination of profit from both technology/consumer products and new drugs could “usher in the first trillion dollar pharma company.”

If we are predicting from historical patterns, the next generation of pharmaceutical companies could already exist. In looking for the newest generation of global corporations with steady profit streams—the modern tech giants are at the top of the list.

Interestingly, Alphabet has actually explored this, launching their own aging biotech called Calico Labs. After their success with AlphaFold, Google DeepMind launched Isomorphic Labs, an AI-focused drug discovery company. With their capital reserves, Alphabet and the other tech giants realistically have the capacity to take many different shots on goal at leveraging technology to discover new drugs.

One reservation I’ve had about this concept is whether it is possible for a tools company to retain a competitive advantage in discovery. If you are selling your unique technology, how can you still capture vertical value with it? When I expressed this concern to Brandon, he countered with an interesting analogy: in the video games industry, Epic Games does exactly this. They create and sell popular games like Fortnite, while also selling Unreal Engine—the software platform they use to make games with.

While it is still early days, I am excited to see whether or not this strategy can take hold at the intersection of technology and biology in the coming years.

Thanks for reading this essay about the origins of drug discovery companies. If you don’t want to miss the next preprint highlight, biotech essay, or startup analysis, you can subscribe to have it delivered to your inbox for free:

Until next time! 🧬

I had the good fortune to work with Deerfield at my last job. Those guys are not messing around

Enjoying dipping into your newsletter. Good origin stories. Are you aware of how French/German (to some extent UK) patent laws drove the Novartis-Ciba-Geigy and the Hoffman-Roche groups to Basel and that’s a part reason for the Swiss pharma strength today ??

Also, in terms of future - seems like a win for the CROs. AI to discover it but you still need CROs to develop them and trial esp. if you don’t have large pharma infrastructure.