Learning venture

Reflections on the 8VC Bio-IT Fellowship

Welcome to The Century of Biology! Each week, I post a highlight of a cutting-edge bioRxiv preprint, an essay about biotech, or an analysis of an exciting new startup. You can subscribe for free to have the next post delivered to your inbox:

Enjoy! 🧬

Overview

When I started this newsletter, I wrote exclusively about scientific preprints. I was working remotely developing open-source software in genomics, and gearing up for grad school. I maintained the same reading routine that I had started when working in a genomics lab, but didn’t have anybody to talk with about cool papers. I decided to write about them and share my essays on the Internet.

I assumed that primarily researchers would read it. I personally knew the sensation of having far more PDFs in my queue than I could possibly actually read. My original motivation was to provide short explanations of exciting results to consume as a supplementary reading habit.

While researchers did subscribe, I noticed that investors and venture capitalists were also signing up at nearly the same rate. Who were all of these people diligently reading a newsletter about new genomics papers that weren’t actually scientists themselves?

I started to read about the world of VC, and interacted with more investors. Scientists hold a range of attitudes towards investors—some are wary of being manipulated, others have a distaste for perceived hype or marketing. However, in my exploration I’ve met many deeply optimistic, ambitious people who are trying to build models of the world to understand what will come next. Given that I spend a huge amount of energy trying to do this, I was excited to learn that it is a job!

My interest in VC only grew after I wrote an essay about software in the life sciences. I talked about some of my frustrations as a scientific software developer, and the ways that the academic grant model can make life challenging for tool builders. There was radio silence from any grant agency, but an outpouring of interest from researchers, philanthropic institutes, and private investors.

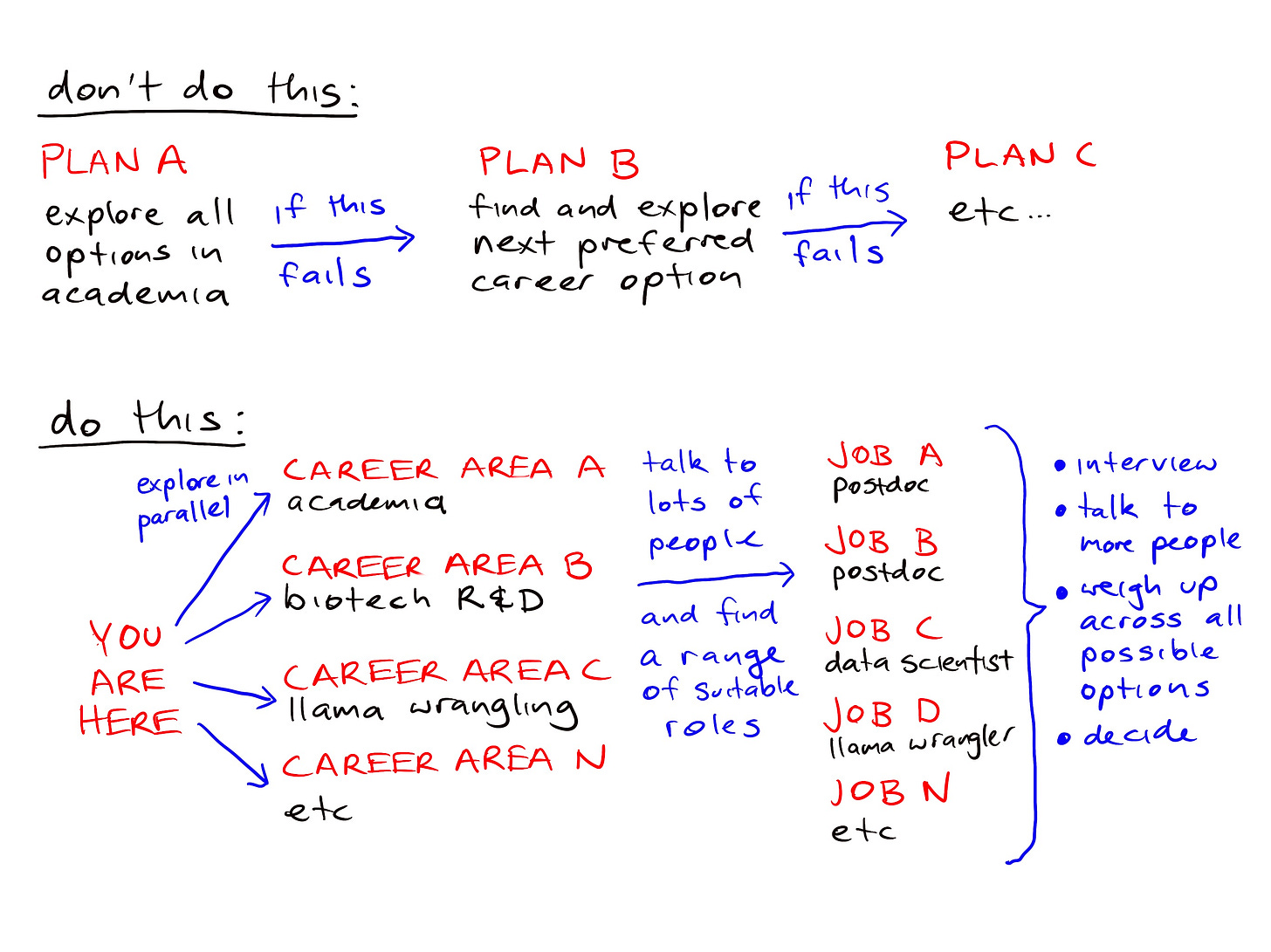

In the spirit of the great career advice offered by Daniel MacArthur, I decided to launch a parallel exploration of the VC world while continuing my own research. I wanted to see how this alternative model for allocating capital to scientific and technological efforts actually works in practice.

I was extremely fortunate to land a spot in this year’s 8VC Bio-IT Fellowship program. 8VC is a leading fund based in Austin and San Francisco that has historically had a lot of success investing in tech solutions based on their Smart Enterprise thesis. In recent years they have become a serious contender at the intersection of technology and biology. Today, nearly a third of the fund’s investments are in biotech. This actually made the fund a good fit for me, because my emphasis on software and data is very consistent with the Bio-IT thesis.

This fellowship was a crash course in the world of cutting-edge biotech VC. We learned about how investors evaluate companies and technology areas, met with founders to learn about their experiences, and explored the new opportunities that we were most interested in to create our own theses.

I’m not going to try to summarize everything that I’ve learned from this experience. Instead, I’m going to talk about the three lessons that have stuck with me the most:

Assessing risk

The power law of returns

Humans are everything

Let’s jump in!

Assessing risk

If you are trying to create something new, there is inherently a chance that you will fail. Scientific venture capital funds exist for one sole purpose: to bet on new companies that have some chance to succeed and change the world. Given that every company is an experiment, what models can we use to evaluate their likelihood of failure?

At 8VC, we learned about the emphasis on trying to analyze three risk models:

Market risk

Team and execution risk

Science risk

Market risk assessment is the most foreign to practicing scientists. Here, the question is: given the success of this company, is there actually an opportunity for substantial revenue? When thinking about an instrument or tool, how many people will actually buy it and use it? For a drug, how many patients are there? How many competing products will there be? While investors all weight these risk models differently, Elad Gil has argued that markets are the most important determinant of success for startups.

If it seems like there is actually a market for the technology being developed, there is still no guarantee that a company will succeed in creating it. A critical question to evaluate is how capable the founding team is of actually delivering on their dream. For a complex discovery platform based on genomics and chemical biology, do the founders have the skills necessary to turn their vision into reality?

Finally, is there actually a sound scientific basis for the company’s mission? How many technical hurdles need to be overcome to achieve success? This helped me understand why all of these analysts were feverishly reading my newsletter about preprints and asking technical questions. This is also where having deep technical experience can be critical: many of the investors at 8VC have PhDs or direct experience as engineers.

I found this type of upfront risk modeling deeply interesting. While scientific projects are by their very nature not guaranteed to succeed, scientists don’t often spend time formally outlining risk. This connected in interesting ways with a course I took this quarter at Stanford with Chris Walsh and Michael Fischbach. They argued that scientists should fundamentally do more of this type of analysis. We should be more explicit about the potential upside of our projects, and weigh it against the scientific risk and our own capability to succeed.

Over time, the NIH has decreased its risk tolerance. Grants now require substantial preliminary data to be funded. It has reached the point that scientists argue they are literally applying for funding for a project they have already done. In this climate, it was interesting to see a rapid funding process where the goal was to understand the risk being taken, not to completely eliminate it. As David Yang emphasized, the point is to find a reason to say yes.

The power law of returns

Risk assessment is only one part of the decision making process. VC funds operate as intermediaries between capital providers—called Limited Partners or LPs—and cutting-edge companies. In order to keep their doors open, they need to make a considerable return on their investments.

Over time, it has become clear that venture returns follow a power law distribution. For early-stage technical companies with ambitious goals, failure is a far likelier outcome than success. Even out of the companies that do succeed, there is a high variance in their magnitude. This is a foundational part of Silicon Valley philosophy, and Peter Thiel described this in Zero to One, saying “The biggest secret in VC is that the best investment in a successful fund outperforms the entire rest of the fund combined.”

In practice, this means that venture capitalists are constantly asking themselves whether a given startup has the potential to be the next generational company with the potential to create a totally new market. Admittedly, I’ve had some reservations about this—and it was something that we spent considerable time talking about.

Coming into the fellowship with an interest in funding scientific tools and software, I didn’t feel like some companies that deserved funding ever had the chance to be the next Meta. For example, one of my favorite products is RStudio, which is an IDE for the R statistical programming language. The company that ships this product is a Public Benefit Corporation, with an explicit charter to use large portions of their profits to fund development of the hundreds of open-source software packages they maintain. While they are stable and profitable, they are unlikely to ever IPO or be acquired.

I would love to see far more companies like RStudio exist in the world—and this may be a more realistic return profile for many scientific software companies. Is there any way that this type of company could actually be a viable venture investment? When researching this question, I was excited to come across TinySeed and the Calm Company Fund, which are both exploring new investment mechanisms that could make this possible.

The shared idea across these funds is that there should be a third way for investors to make a return instead of solely relying on massive public listings or acquisitions. If a startup becomes stably profitable—this should be a win for both founders and investors. I’ve also wondered whether this is an opportunity for actual value creation for Web3. Careful token design could lead to more fluid formation, funding, and returns for all parties involved in new projects. We should develop systems to flexibly fund both types of opportunities: the next rocket ships that are highly scalable, as well as biotech Mittelstands that could help create a more robust Bioeconomy.

I think that this could be a wide open opportunity in the life sciences. New VC funding mechanisms have the potential to create totally different career options for scientific method developers. While this type of work isn’t always recognized by academic grants or career progression, these scientists could have the opportunity to create enduring businesses around their open-source contributions.

Humans are everything

At the end of the day, all of this comes down to humans. Markets are just a crazy emergent system for human communication. Science is a deeply human pursuit. An entrepreneur is only as good as the humans they can convince to join them on a high-risk pursuit of changing reality. Venture capitalists are only as good as the humans they support. Humans are central to any funds raised, and any new company backed.

It doesn’t matter what you do, life is a team sport. One of the partners Francisco Gimenez challenged us to lean into this. He argued that you actually can get incredibly far with an earnest orientation towards being nice and helping people—and that it should be more than a VC trope. Importantly, in a world with so many meetings—a good goal is to try to leave people feeling more energized at the end of the meeting than at the beginning. It reminded me of a Maya Angelou quote my mom always told me: “I've learned that people will forget what you said, people will forget what you did, but people will never forget how you made them feel.”

Because of this, I’m deeply grateful to have learned so much from the team at 8VC and the other fellows this Spring. It was incredibly energizing to be around such intelligent and optimistic people looking to help shape the future for the better.

I also feel fortunate about the awesome friends that I’ve made on the Internet, and that I have the opportunity to stay a part of the world of VC, but more on that in the coming weeks…

Thanks for reading this essay about my learning experience at 8VC. If you don’t want to miss the next preprint highlight, biotech essay, or startup analysis, you can subscribe to have it delivered to your inbox for free:

Until next time! 🧬